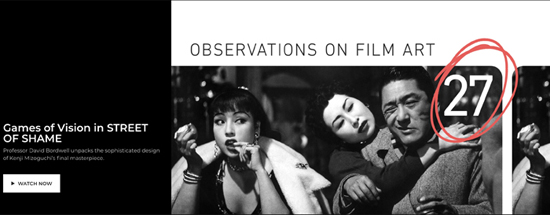

Street of Shame (1956).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Kenji Mizoguchi

DB here:

So much of contemporary film and TV take pictorial space for granted. Yes, The Avengers: Endgame stuffs its frame with, well, stuff, but you’re seldom given time to see everything. Even in films not so dominated by CGI, if the the actors’ faces and gestures come across and you can hear the line readings, that’s pretty much enough. Most of the rest is there to fill out the very wide frame.

“Wait,” I hear someone saying. “Thanks to Steadicam, directors use camera movements to sweep through space all the time.” Yeah, that’s just my point: They sweep through. We’re following characters’ backs or fronts, not exploring space as such. Very seldom do we get a chance to probe what’s revealed, except in carefully wrought movies like Sunset (which tease you into trying to discern what’s not even in focus).

Moreover, today the pace of the editing is so fast, even in an “intimate” movie like Booksmart, that the actors’ faces dominate everything. For fifty years many directors have been “shooting for the box,” shoving their actors into close-ups that will read on TV, now on computers and smartphones. Like the endlessly moving camera, the big heads and the quick cuts refresh the image often enough to hold our interest in a distracting environment.

Granted, most filmmakers now supplement their fast-cut, rapid-pan close-ups with an occasional landscape shot that can look pretty, in a calendar-image sort of way. Overhead shots, now facilitated by drones, swoop us through the towering corridors of The City or across a swath of forest in a way that is undeniably impressive. This convention doesn’t count, for me, as pictorial intelligence unless somebody like Tony Scott does something, however nutty, with it.

I’m not against these stylistic choices per se; every style is valid if it’s pursued with imagination, rigor, and delicacy. Nor am I suggesting that the other extreme, so-called slow cinema, is inherently more virtuous. Long unmoving takes can be paralyzingly dull. Ozu made fast cutting just as “contemplative” as Hou or Tarr, because he knew how to design pictures.

It’s just that the norms of intensified continuity and the “free camera” have overwhelmingly dominated current practice. It’s worth remembering other ways moving pictures can be. One way to do that is to revisit film history, and the work of Mizoguchi Kenji is an ideal place to start.

His Street of Shame (1956) is the subject of this month’s Observations entry on the Criterion Channel. In it, I invite you to join me in attending a master class in staging.

The theme is Mizoguchi’s perennial one, that of the ways in which women succumb to or resist their oppression in a patriarchal society. We’re in the Dreamland brothel, where five–eventually, six–women are working at the very moment the government debates eliminating prostitution. Mizoguchi shows how they both cooperate and compete, trying to quit, deploying different strategies for managing their clients, and just getting by. It’s all done through what Mizoguchi called the “hypnotic power” of carefully choreographed images.

A personal note

In a way, Mizoguchi made me a film teacher.

During the week of 25 September 1969, what could you have have seen in Manhattan? I Am Curious: Yellow, La Chinoise, Closely Watched Trains, Miracle in Milan, Hell’s Angels ’69, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Midnight Cowboy, The Killing of Sister George, De Sade, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, One Second in Montreal, <—->, Take the Money and Run, Alice’s Restaurant, Medium Cool, In the Year of the Pig, Easy Rider, Putney Swope, and programs of Kubelka and Jack Smith movies. There were many double bills on offer: The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, Yellow Submarine and The Gold Rush, King Kong and The Lady Vanishes, Seven Samurai and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, Monterey Pop and Don’t Look Back, The Deadly Affair and Funeral in Berlin, Little Sister and Alice in Acidland, Lonesome Cowboys and Flesh.

In the city for only a few hours, I didn’t go to any of those shows. There was yet another double bill at the Bleecker but I could catch only one title: not Lola Montès (I would see that in Paris a year later), but Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff.

As a teenager I had read books about cinema (Welles, Hitchcock) and in college I’d written movie reviews and participated in a film club. Now, newly graduated, I was teaching high school. The only Japanese films I’d seen were the Kurosawa standards our club programmed. Despite planning for a career in high-school teaching, I thought about film most of the time. In the pages of Film Culture and Movie I had read about Mizoguchi.

I came out of Sansho with tears streaming down my cheeks. I heard two young men in the lobby talking about the film. Did they go to NYU or Columbia or some such place? All I know was that they loved Mizoguchi’s long takes, as I did. Somehow, those takes had to be connected to the way the movie hit me. I thought something like: I’d like to study this sort of thing.

I returned to my apartment and began figuring out how to apply to graduate school.

Mizoguchi was still largely unknown, certainly unappreciated. The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing Sansho until it resurfaced in a later run. Roger Greenspun made up for the neglect with a a gracious note.

“The Bailiff” is a film of breathtaking visual beauty, but the conditions of that beauty also change–from the etheral delicacy of its beginning (before the kidnapping), through the dark masses of the Bailiff’s compound, to the ordered perspectives of Kyoto and the governor’s palace, and finally to the spare symbolic horizons at the end.

In effect, it moves from easy poetry to difficult poetry. Its impulses, which are profound but not transcendental, follow an esthetic program that is also a moral progression, and that emerges, with supreme lucidity, only from the greatest art.

People talked that way then, with good reason.

Choreography all the way down

I didn’t see much Mizoguchi in the years following. There wasn’t much available. (And Ozu was unknown to us.) I did see Ugetsu and Street of Shame, though they didn’t grab me as fast as Sansho had. Fairly soon, though, New Yorker Films and Audio-Brandon made prints of other Mizoguchi titles available. I started using Mizoguchi films in my teaching, and the more I studied them the more I admired them. I was also inspired by critics Robin Wood and Noël Burch, who sought to explain the emotional and cinematic force of this filmmaker.

I began studying Mizoguchi’s films, traveling to Europe to see them all and make frames from prints. Eventually that work would inform my chapter on his staging in Figures Traced in Light. Although there he bested me two falls out of three, I think that discussion made some headway in analyzing his unique visual strategies. I tried to develop those ideas further in an online supplement to that chapter and in the blog entries “Secrets of the Exquisite Image” and “Sleeves.”

More skilfully and subtly than nearly anybody else, Mizoguchi arranges bodies in space to create powerful pictures. Yet his gorgeous shots aren’t just decoration. He never lets the images, elegant as they are, distract from the dramatic issues arising among the characters. The result, I argue, achieves the sort of “hypnotic power” that Mizoguchi claimed to seek.

In Mizoguchi, I suggest, a fairly dense image “becomes a story” as its elements start to mingle and separate out, letting our eye discover (with guidance) a drama as it emerges. A situation precipitates out of a rich mass of material, and the result is an accumulating tension that’s at once dramatic and pictorial. He evidently learned a lot from von Sternberg, but I think this thickening-and-release dynamic of story and style is reminiscent of Hitchcock or Lang as well.

The students were right: Mizoguchi is a master of the long take. The long take, he said, “allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.”

But we shouldn’t think of this technique in the sort of marathon-competition terms people apply to long takes nowadays. (The current example is Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Today’s long takes are often virtuoso traveling shots. While Mizo made wonderful use of camera movement, he knew the power of stillness. He showed that you can just clamp the camera on the tripod (or the crane) and sculpt the action in front of it.

Among Mizoguchians, there are some who find his later films stylistically compromised. Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942; below) and Loves of the Actress Sumako (1947), with their far-off figures and impeccable, “all-over” compositions, merge austerity and density in ways almost inconceivable today.

Given this radical approach, his greater reliance on closer views in the 1950s work can seem a step backward.

But Mizoguchi was a pluralistic director from his earliest days forward. As I try to show in Figures, he fitted his visual design to the needs of a scene, and even the most severe films draw on diverse techniques. Street of Shame shows his endless resourcefulness in enriching three-shots and two-shots and singles. He found choreographic possibilities at every shot scale, with small gestures and glances becoming as important as characters shifting around the set. In the last shot of the last film he made, a single darting eye commands the image and carries the drama.

Given the sustained shot, Mizoguchi fills it and drains it, re-fills it and thins it out and channels it to a climax, all with a graceful, nearly unobtrusive choreography always driven by the emotions pulsing through the scene. I go back constantly to Philippe Demonsablon: “He emits a note so pure that the slightest variation becomes expressive.”

Mizoguchi works in melodrama. Some directors, such as Sirk, take intense situations and amp them up. But Mizoguchi, like Stahl and Preminger, is always banking the fires. His style presents hot emotions in a cool way, betting that detachment and restraint give the emotions a sort of stark purity. If more filmmakers studied his work, who knows what kind of cinema we might have? I hope you have a chance to check in on this entry.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole fine Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts.

Street of Shame is also available on a generous Criterion Eclipse DVD set. Some years back Masters of Cinema series gave us beautiful Blu-ray transfers of many Mizoguchi films. The Street of Shame edition has a fine feature-length audio commentary by Tony Rayns. Alas, the set including the film has apparently gone out of print.

Robin Wood’s influential essay on Mizoguchi is “The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Gatherer,” in Personal Views: Explorations in Film (Gordon Fraser, 1976), 224-248. Noël Burch’s revisionist account of Japanese cinema is To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), where chapter 20 is devoted to Mizoguchi. (The book is available online here.) Roger Greenspun’s review, “‘Bailiff’ Returns,” appeared in the New York Times (17 December 1969), 61.

For more on the place of Japanese directors in film culture, you can try this entry on Kurosawa and this one on Shimizu.

Street of Shame (1956). The sign reads “Cooperative Association Members” and “Confidential Membership.” Thanks to Steve Ridgely for the translation.

0 comments:

Post a Comment