Welcome to How’d They Do That? — , a bi-monthly column that unpacks moments of movie magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off. This entry looks into the reverse melt sequence in Hellraiser.

At its core, Hellraiser offers a perverse portrait of domestic debauchery: Macbeth by way of interdimensional S&M. Released in 1987, the film marks the directorial debut of macabre renaissance man Clive Barker, whose dissatisfaction with prior cinematic adaptations of his work pushed him to finally take the reins himself.

When Hellraiser begins, meek but loving Larry (Andrew Robinson) is moving his family into the derelict house of his brother Frank (Sean Chapman). The move, Larry hopes, will act as a fresh start. A new beginning, and maybe even an opportunity to re-light the spark with his cold, unloving wife, Julia (Clare Higgins).

Frank, you see, is missing. Torn to shreds, quite literally, in his hedonistic quest to experience the full spectrum of pain and pleasure. As far as Larry is concerned, Frank’s mysterious disappearance is par for the course. But Frank’s absence haunts Julia. For this is, in fact, a tragic love triangle: a familial struggle between a pervert, his lover, and her husband.

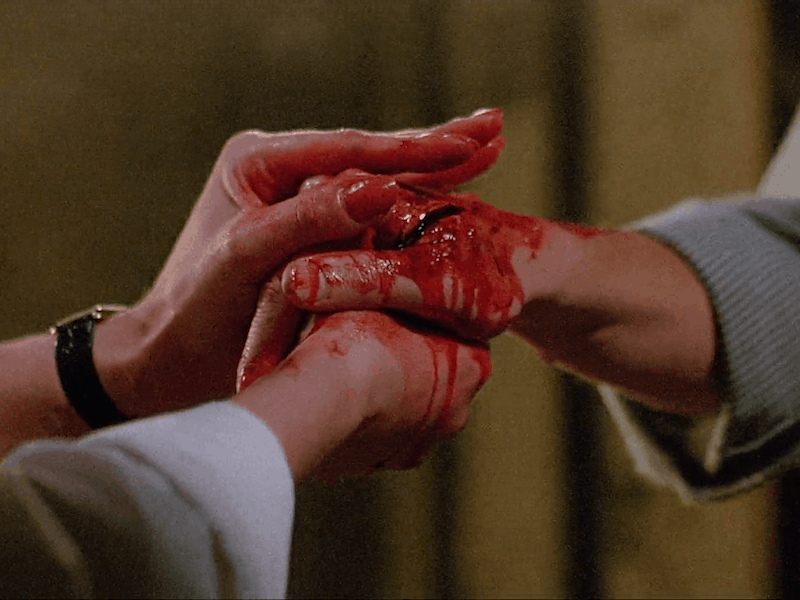

Lurching into memories of her affair with Frank, Julia’s longing for her lost passion inevitably releases something nasty. While she reminisces vividly, Larry slices his hand open on a stray nail. Dizzy at the sight of blood, Larry finds his wife, lost in thought, in the attic. In the very room where Frank unlocked the occult puzzle box that tore his soul (and his body) apart.

While Larry leaks profusely onto the floor, a disgruntled Julia accompanies her pitiful husband downstairs. And so, the couple inadvertently perform a sacrifice. Part blood, part divination: flesh to flesh, as it were. Something dormant awakens beneath the floorboards: something fleshy, stubborn, and determined to live again.

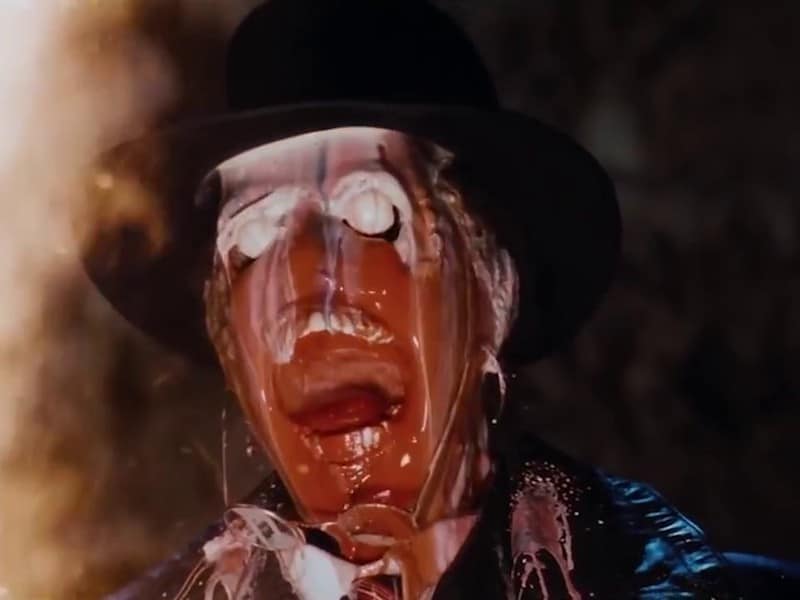

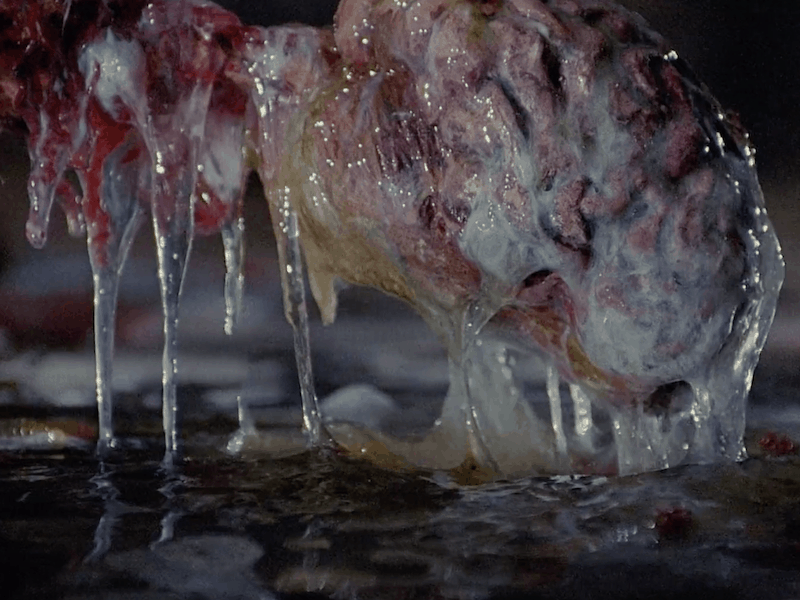

Christopher Young‘s excellent, sadistic score kicks into high gear. And steadily, painfully, Frank pulls himself back together again. Liquid willfully materializes. A slimy spinal column reattaches to the base of a reconstituted brain. Veins and nerves form out of thick, cloudy puddles. Eyes push out and sockets snap open.

This isn’t just one of the best special makeup effects in the film. This is one of the most memorable effects sequences in ’80s horror, period. Iconic cenobites notwithstanding, this is Hellraiser‘s greatest visual achievement: a startling transformation in which the germ of a man rips himself out of one world and back into ours.

How’d they do that?

Long story short:

With a false floor, lubed-up puppets, and reverse-photography of melting wax.

Long story long:

The great Bob Keen designed the special makeup effects for Hellraiser. While only in his mid-twenties, Keen had amassed an impressive list of credits that included the likes of the original Star Wars trilogy, multiple Jim Henson films, and a handful of projects under his mentor Nick Maley. It was through Maley (or rather, through Maley getting sick) that Keen was tasked with designing the makeup effects for Highlander, which put Keen on the radar of Hellraiser producer Christopher Figg. Hellraiser would be the first feature film of the upstart SFX studio Image Animation, which Keen co-founded with Hellraiser‘s workshop supervisor, Geoff Portass.

According to Portass in the impressively long making-of documentary Leviathan: The Story of Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II, the “birth of Frank” sequence as we know it almost didn’t happen. The initial approach of the financiers was to treat the project like a cult object. One that, on the strength of Barker’s literary reputation, would prove a safe investment. However, after the backers obtained a post-production cut of the movie, they liked what they saw. And so they smartly threw more money at the film. Ultimately, a good chunk of that money went into the “birth of Frank” sequence.

That original cut of the film went something like this: clumsy Larry slices his hand open, the camera cuts away, and bam: Julia finds skinless Frank in the attic. This extra dough allowed Keen and a small team to bring to life the nasty shit that took place during that cut.

In the script, as written, the idea was that Frank, or what was left of Frank, had been splattered all over the walls and dried up over time. As scripted, the husk of Frank was supposed to materialize out of a wall and start talking. The original plan was to accomplish this with animatronics. The team even built a cable-controlled lip-synching puppet. However, according to makeup crew member Cliff Wallace, the puppet proved “too complicated for its own good.”

Instinctually, Keen knew something was missing from the birth sequence. Over the course of principal photography, “the film had become something else.” And the dry birth, as scripted, just “wasn’t visceral” enough. As a result, the team scrapped the idea of dusty Frank in favor of a… wetter approach. One that, according to Barker, Keen had conceptually wanted to do for a very long time: a living corpse reconstituting itself from the ground up.

“I found it interesting to start with the bare bones and work up to something quite skinny but definitely alive,” recalls Keen in Fangoria #66. “A total reversal to the usual effect where you’re making someone decompose.” (Speaking of “quite skinny but definitely alive,” wispy actor Oliver Smith was the one who embodied “Frank the Monster.”)

The realized birthing sequence is an entirely in-camera effect, shot on a stage in South London well after principal photography had wrapped. The re-constituted attic was, in fact, the only part of the film shot in a studio. Where, helpfully, the crew had the luxury of a raised stage. This allowed for the effects team to operate the puppets and pumps from underneath the floor.

The shot of Larry’s blood seeping unnaturally through the floor was a simple reverse shot of a red fluid being pumped up through rigged nail holes in the floorboard.

The false floor allowed for the establishing downward pan revealing the pulsing heart-like mass. This “embryo” was designed by John Cormican. And as Keen relays to Heather A. Wixton in her book Monster Squad, the effect was “made out of a condom, a piece of tubing, some glue, and some bits and pieces to pull the whole thing together to make it look like a real human organ.”

According to the crew, the backbone of Hellraiser‘s special effects was, in fact, lube and condoms. Which, given the erotic nature of the film, is quite fitting. The crew actively sought out condoms because they were made out of latex. And sheet latex was something constantly in need if you were doing SFX makeup in the ’80s. Lube made things look wet (and stay wet) under the camera lights. According to the crew, they were mortified whenever they’d have to make a run to a shop to load up on what surely looked like a king’s ransom of orgy supplies.

As for the birthing sequence, the SFX gang actually used a step up from lube. That’s right: it’s the return of our good friend methylcellulose, the food thickener/SFX mainstay. “We would pump up methylcellulose by the gallon” recalls Keen. You can see the pump in action early in the sequence, as pools of clear goop ooze up from the floorboards. The thick, snot-like strands coating Frank’s in-progress body are also likely methylcellulose.

When Frank’s “arm stumps” (what else to call them?) erupt from the pools of ooze, those are two animatronics. “We built lots and lots of puppet rigs,” stresses Keen. Watching the sequence, the puppetry is especially apparent when you know about the false floor. You can just imagine the operators, huddled below, pushing out fingers, and pulling on shuddering spinal stalks.

The forming flesh effect itself — where bone, muscle, and tendons reconstitute Frank’s skinless body — was accomplished with wax and reverse photography. The team constructed models of body parts out of different waxes with different melting points, layering them as needed. Burned and filmed in reverse, the effect is that of re-forming flesh. This required a multitude of stages as well as close-up appliances to show the growth of Frank’s hands and organs.

The crew also used colored thread for Frank’s veins, which when pulled and played in reverse, looks like conscious, slime mold-like sinew. As mentioned above, puppet rigs also featured in the “reverse melt” parts of the sequence. Wires were used to pull away pieces of Frank apart bit by bit, mimicking, in reverse, the in-film demise of the character himself.

“The sequence involves a whole bunch of ideas merged into one, and I don’t think that’s been done before,” emphasizes Keen.

What’s the precedent?

As far as reverse decompositions go, Keen is probably correct in saying that there is no precedent. Especially at this scale. However, I can think of at least two pieces of early ’80s SFX that put some of Hellraiser‘s ingenuity in context.

The first is a melt. In fact, maybe one of the most famous melts of all time. And, like the Frank birth effect, it made use of heat and liquifying materials layered to give the impression of human flesh. That’s right, we’re talking Raiders of the Lost Ark. In which, near the end of the film, Steven Spielberg treats us to the unforgettable image of two Nazis’ faces melting off.

Luckily for us, the good folks at Industrial Light & Magic have spoken about the effect at length. Probably because traumatized kids who are now entertainment journalists won’t stop asking them to foot their therapy bill.

After making molds of the actors’ heads using alginate (a rubbery substance used in dental molds), the artists sculpted the heads and added eyes and skulls made out of a material that could withstand the face-melting heat. Instead of wax, ILM used different colored layers of a gelatin formula with a low melting point. Then it was just a matter of aiming the heat guns at the heads and speeding up the recorded footage.

The other effect I want to mention is from John Carpenter’s The Thing. We’ve covered the Norris-Thing effect on the column before (and at length). But I want to highlight one moment from the sequence in particular: when Norris-Thing’s fleeing head defensively sprouts legs and eyestalks. In terms of “pushing gross spindly shit up through a fake floor,” it’s the effect that springs to mind. So to speak.

The Norris-Thing’s transformation isn’t all that dissimilar from what Keen and co. did for Frank’s limbs in Hellraiser. To achieve the effect of the metamorphosing Norris head, The Thing SFX team, lead by wunderkind Rob Bottin, worked on an elevated set with a fake floor. This allowed the operators below to push everything up and out through Norris-Thing’s hollow head.

There’s a lot of love out there for 1980s special makeup effects. And I’d venture a guess that a good part of that love is rooted in the period’s penchant for texture. Whether it’s a crab-head, a goopy corpse, or a melting Nazi head, these are effects with an endearing tactility. They certainly touched audiences. Whether audiences would have the guts to reach out and touch them back is another matter.

0 comments:

Post a Comment