Welcome to How’d They Do That? — a bi-monthly column that unpacks moments of movie magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off. This entry looks into the making of The Blob.

The texture of horror films in the 1980s was goop. Viscous, visceral, and virtually everywhere, slime was a cost-effective way to enhance creature effects and convey a horrifying sense of tactility. And as far as ’80s slime goes, they don’t get much slimier than Chuck Russell‘s The Blob, a sci-fi horror-comedy about a meteorite-hopping pile of goop wreaking havoc on a small California ski town.

Despite being a body horror remake of a 1950s classic, The Blob is rarely mentioned in the same breath as Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Thing, and The Fly. The 1988 version of The Blob retains more of its B-movie roots than the aforementioned auteur-driven efforts. It’s campy, comedic, and has a lighter spring in its step. Which is to say: it’s easy to dismiss.

Indeed, historically, the remake of The Blob has had a bad rap: “Needless, if undeniably gooey,” Leonard Martin put it. I’m not going to argue that Russell’s remake is of the same caliber as Kaufman’s, Carpenter’s, or Cronenberg’s. But I do think Russell and Frank Darabont’s sharp script is under-praised, efficient, and more subversive than folks give it credit for. (Shadowy governments sacrificing a handful of innocents to save face? Why does that sound familiar?).

By Russell’s own admission, The Blob didn’t get a proper shot during its theatrical run: “It was released late in a very hectic summer filled with big films,” he says, “and it didn’t have a particularly good ad campaign.” Thankfully The Blob took on a new life in the era of home video. It certainly helped that The Blob has one of the most horrifying VHS covers of all time. Indeed, as much as I will vouch for the film’s underappreciated charms, the reason The Blob has survived all these years is its effects.

Made right on the cusp of the CGI takeover, The Blob is a snapshot of a high watermark of practical creature effects-work. As a result: the Blob itself is a brain-buster to look at. Unlike its 1958 predecessor, this Blob is fast. It moves up walls, across ceilings, and through sewers, like it has a mind of its own, oozing in different directions, pulsating, and flowing with terrifying ease. I get monsters in suits. I understand puppets. But how do you build a creature like the Blob? And how do you control something that unwieldy?

How’d they do that?

Long story short:

Puppeteered silk blankets injected with a common food thickener.

Long story long:

The Blob was realized through the combined efforts of creature effects coordinators Lyle Conway and Stuart Ziff, and makeup effects wunderkind Tony Garnder (“I lied and said I was 25“), with post-production opticals and miniature work by Greg Jein, Dream Quest, and All Effects. The stratified teams worked out of a former auto-repair shop, aptly re-christened “The Blob Shop.”

In keeping with its vexing nature, the daunting task of bringing a sentient pile of space goo to life frequently eluded the filmmakers. “Part of the problem was that the Blob hadn’t been properly locked down from the beginning,” confesses VFX supervisor Hoyt Yeatman in American Cinematographer Vol. 69. Effects were handled by different groups, which in some instances backfired and resulted in “very little usable Blob footage during production.” As straightforward as a blob might sound on paper, “it proved very difficult to get a performance from it,” explains Yeatman.

Eventually, the filmmakers settled on a guiding concept. As relayed in a two-part profile by Fangoria‘s Bill Warren: the Blob was “a giant, inside-out vampire stomach.” The idea was that the Blob was highly acidic. So instead of just absorbing whatever it touched, the Blob’s victims would dissolve at different speeds depending on the creature’s strength.

Before leaving the production (in frustration, supposedly), Conway resolved one of the Blob’s big “performance problems.” In shots where its movement was limited, the Blob was sculpted full-size and cast in stiff rubber. When a lot of movement was required, Conway’s team developed a puppeteering device called the “Blob quilt”: layered silk with “ravioli-sized pockets” injected with methylcellulose, a food additive derived from wood pulp. The methylcellulose would secrete through the silk, obscuring the base structure and allowing the puppeteers to manipulate the apparently fluid mass. One of the ways they would puppeteer the quilt was with “mitten-like Blob chunks,” that hid the hand-shapes of the operators. In addition to keeping its shape, the design of the quilts produced small surface movements as the sacks jiggled of their own accord.

There were, however, some drawbacks: a veiny quilt of ooze took hours of prep, the puppeteering was doable but basic, and water-retention made the quilts very heavy. “Those quilts were two-hundred pounds of slime,” according to puppeteer and mechanic Peter Abrahamson. As creature effects crewmember Jeff Farley puts it: “There was not a day when the puppeteering crew would not go home covered in slime. We would wear plastic garbage bags to try to cover ourselves, but it never worked.”

The Blob quilts were draped over everything from fiberglass forms to mechanical armatures, to air bladders, and even over the puppeteers themselves. Additional Blob material included — but is probably not limited to — vinyl, urethane and foam latex, lycra, nylon, rubber, and gallons of commercial “Slime.”

Miniature sets and actor stand-ins were used and composited together in post-production. They even built an entire mini version of the town of Abbeville in a 1:8 scale. While the Blob’s movement was primarily hand, wire, and rod puppetry, some stop motion was used. You can glimpse a brief stop motion sequence in the theatre scene. The sequence is noticeable thanks to a strobe light effect and because of the contrast with the high-speed live-action miniature work.

Now, speaking of compositing: The Blob’s shiny surface created a real headache for optical matting. Because the Blob’s slimy surface was reflective, front-projection blue-screen set-ups were much more effective for pulling mattes off the Blob. “Everything had to be composited in optical in order to ensure the Blob’s actions coincided with what was happening in the background and foreground of each shot,” explains Yeatman. Since many shots mixed frame rates, the crew employed a density control device to maintain control of the variable frame-rates.

Detailing every effect in the film would result in a very informative if exhaustive SFX textbook. So, for your sanity and mine, let’s look at a single, iconic scene: the death of Donovan Leitch Jr.‘s football jock Paul — a.k.a. “the guy in the blob” sequence. This is the scene that adorns the film’s traumatizing VHS cover: the gasping white-eyed face encased in hungry goop.

Up to this point, the first act of the 1988 remake adheres pretty closely to the original. But, borrowing a bait-and-switch trick from Psycho, Darabont and Russell reveal that, while he seemingly fit the bill, Paul isn’t our Steve McQueen surrogate — Meg (Shawnee Smith), his girlfriend, is. The rug-pull is especially effective because Paul doesn’t just die…he suffers.

Shot at the end of the schedule, the sequence came together very quickly. Like, “in less than a week” quickly. While Conway’s original approach to the scene centered on mechanical miniatures, Gardner “felt puppets were a really good idea in that they would give us a lot more control and permit us to shoot with a wider angle…I also felt we needed Donovan himself to sell the effect.” As Gardner details, the sequence begins as a full-sized live-action effect. And over the course of the scene, there are cuts back and forth between the puppets, miniatures, and the actors.

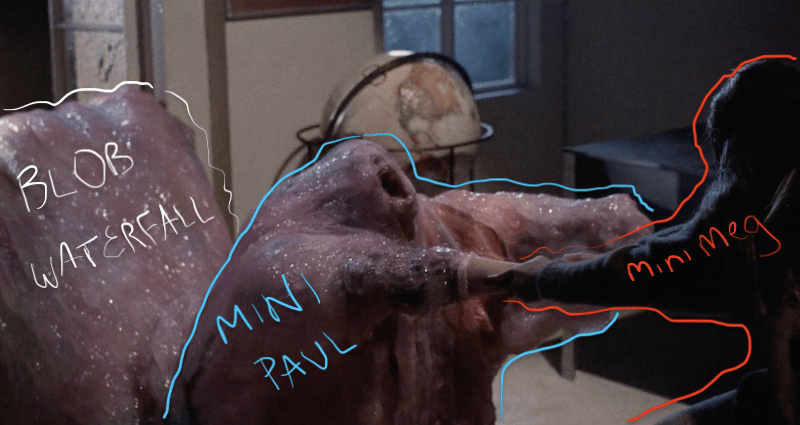

Speaking of puppets, the sequences required the construction of two elaborate rigs: one full-scale rig that would house Leitch, and another smaller rig that would contain Leitch’s mini-counterpart. Both featured a sliding, pivoting Blob-platform that came through the floor. They also included a separate fiberglass piece — covered in vinyl bladders, and Blob quilts — nicknamed “The Waterfall,” which stretched from Leitch’s head to the window behind him. The platform Leitch sat on rolled back into a cavity inside the Waterfall. These components give the impression of the Blob moving in two different directions at the same time: sliding over its victim while moving up the wall and out the window.

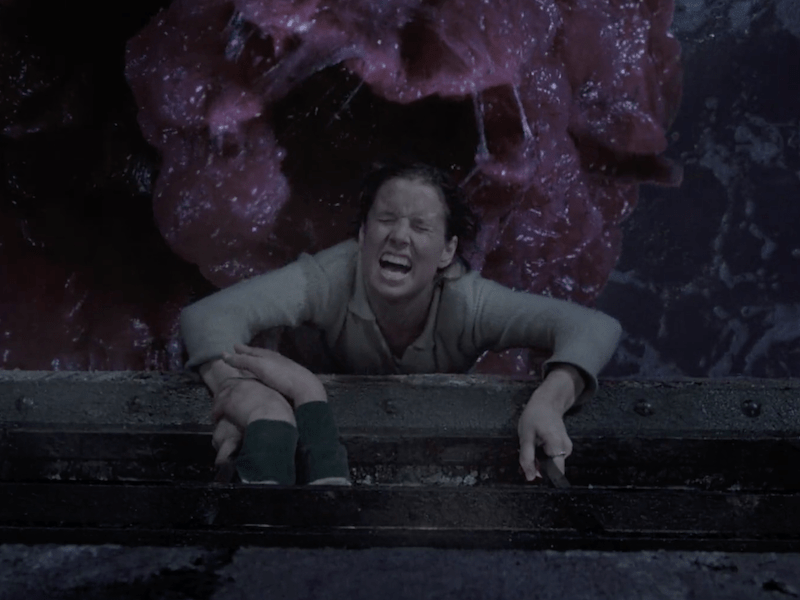

“Donovan spent a day in this horrible rig,” Gardner recalls. “He sat on a small seat mounted on a rolling platform, leaning forward. His body was encased in a translucent pink fiberglass shell, except where his head stuck out past the neck and an area where his right hand was exposed.” When the Blob pulls taut over Paul’s face, that’s really Leitch under there. Reportedly, it felt like being suffocated. Vinyl bladders that worked off air compressors sat directly on top of the fiberglass shell, simulating bulging surface movement. Finer “subdermal” surface movement was accomplished with layered nylon tricot fabrics pulled from different directions at different speeds.

A shroud of Aquapull, a fabric that becomes transparent when wet, was draped over the rig. The painted Aquapull hung over a nylon base with urethane tints and painted veins. Over that went the bulky “Blob Jacket,” a back-zipped vest made up of Blob quilt that fit over the whole structure. “We also used a couple of strips about three inches by nine inches long whose sides were heavily quilted while the center was clear silk with small little pockets sewn into it,” explains Gardner. “These moving pieces were streaked with blue while the pieces underneath were streaked with red.” When the two fabrics crossed, the Blob color-shifted purple. The slime in the quilt pockets was dyed varying colors to convey a sense of depth: a transparent halo around Leitch’s face that radiates out into a deeper crimson.

The sequence called for three visible stages of mechanical effects. First, a miniature of Leitch for the establishing shot of the football player. Then, another miniature of Leitch, with his face distended, holding onto a miniature of Smith. The third was the only full-sized close-up in the sequence: Leitch’s melting face with rolling eyes and a distended mouth — best glimpsed in these behind the scenes photos from Garnder, Zar, and Bill Sturgeon’s Alterian Studios.

To get the effect of Leitch’s face collapsing in, Gardner approached Image Masters, who scanned the actor from the collarbone up and fed the information into a computer that used the data to produce a six-inch wax bust. This was then placed into the Blob to imply a partially-consumed Paul.

For the effect of Smith pulling Leitch’s undigested arm off, the crew made use of an over-the-shoulder “Blob sled,” which consisted of an arm rig with a quick-release mechanism fitted with a fake appendage. Smith would fight against a crew member with a pistol grip release, providing resistance with the sled. “Then all the tendons would stream out, and she’d go flying!” Gardner recalls. “The take they used was the one where the operator got a little trigger happy and let go before she was expecting it, so her look of surprise was really genuine.”

What’s the precedent?

Look, obviously things like story, stakes, and strong characters are important. But at the end of the day, all Blob movies hinge on their special effects.

The Blob of the original 1958 film was created by the special effects team at Valley Forge Films. The effect relied primarily on silicone mixed with red vegetable dye, rendered gloriously on-screen in DeLuxe Color. They also, surprise surprise, made use of methylcellulose. Because silicone flows slowly, time-lapse photography was used to speed up the creature’s movements. Due to technical limitations and to impress a sense of scale, nearly all the shots featuring the Blob were shot in miniature on tilted sets. On occasion, you’ll see the 1958 Blob expand and contract; a lively pulsating achieved by smearing the dyed silicone over a modified weather balloon.

Director Irvin S. Yeaworth sums it up nicely on the original Blob‘s Criterion release: “The special effects certainly were not the star of the movie, though they held their own for the era.” Ultimately, despite being up against the technical limitations of the time and a wildly tiny budget, for what it is, the effects of the original Blob hold up. Sometimes, when you’re up against the wall, a goopy weather balloon will do just fine.

A 1972 sequel, Beware! The Blob... exists. In the film, the Blob is primarily made up of red-dyed powder blended with water. It was also made of other materials including a large red balloon, back-lit red plastic sheets, and a rotating drum of hardened red silicone. The only other thing worth mentioning about the effects in Beware! The Blob is that one of the people who worked on them was cinematographer Dean Cundey, who landed the gig through a connection with SFX Supervisor Tim Baar.

I’m sure the day will come when the Blob re-emerges in the 21st century as an uncharismatic CGI monstrosity. But until then, even at their worst, I cherish these practical piles of goo.

0 comments:

Post a Comment