In our new column Kino Color, Luke Hicks chooses a handful of shots from a favorite film in order to draw out the meaning behind certain colors and how they play into both the scene and the film as a whole. For his first entry, he digs into Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust.

Julie Dash is a slice of visionary splendor so singular and uncompromising that she makes you believe in a new kind of cinema, one detached from whiteness, western worldviews, and male hegemonies. Her aura bleeds through the page and into an emboldened heart or sudden smile.

Dash’s feature debut, the mythical and poetic Daughters of the Dust, remains her masterpiece and her only nationally distributed film. The film is a period piece about the women of the Peazant family, descendants of African captives living on an island off the coast of Georgia in 1902. From the perspective of a phantom “Unborn Child” (Kay-Lynn Warren) to the ancestral ritualism of the matriarch, Nana (an unshakable Cora Lee Day), we witness past, present, and future through the eyes of several generations wrestling with identity, history, and memory.

Among other things, the dreamlike cinematography (by then-husband Arthur Jafa), natural imagery, embedded womanism (feminist theory specific to women of color), alternative storytelling mode, spiritual momentum, existential gravity, and evocation of Black excellence will swell inside your mind for years to come. And the explosion of color makes it ripe for a color theory reading.

I’ve chosen four shots that represent the many ways in which Dash uses color to communicate theme, tone, emotion, style, history, memory, and abstract thought in Daughters of the Dust. Using color theory, I interpret what we can glean from the shots to add layers of depth and insight to Dash’s delightful, depressing, and thought-provoking wonder.

This shot comes near the beginning of the movie, set in the middle of a montage that introduces us to Ibo Landing and the Gullah people awaking into the last full day on the island for all but the old souls. We see a woman mundanely examining tomatoes and putting the good ones in the basket. The candy apple red pops from the image, the sheer vibrance cluing us into the “distinct, imaginative, and original” culture of the Gullah islanders, as the prologue reads.

The lighting is like that of a chiaroscuro painting, casting a shadow as strong as light to create even greater contrast. A color scheme with one high-contrast color that sticks out from the rest is called a discordant color scheme. But, for a relatively simple image, there is a lot at play off-screen.

Red often represents passion, energy, danger, and aggression, all of which could be held in that tomato as it is placed into the straw-colored basket, whose hue represents home, stability, comfort, and endurance. The contrast between the glowing straw basket and the darkness surrounding it makes the photo seem like a still life yet to be populated with food.

That is true to the scenario. Much of Daughters of the Dust is spent nestled into the dunes with the women as they talk and prepare a mouthwatering final meal. But it would be superficial to stop there.

Shucking corn, peeling shrimp, dicing onions, and slicing okra is also the ideological battleground for generational discussion about everything: ancestral tradition, migration, and suffering, to name a few. If the basket is comfort and stability, the tomato is the anger and the energy of the new generations to disrupt that stability through heated, candid discussion. If the basket is home, the tomato is the dangerous-yet-impassioned migration to the mainland to which the film builds. As Yellow Mary (Barbarao) says, “The only way for things to change is to keep moving.”

There is also the chameleonic indigo in the image. The pitch darkness of the unseen woman’s hands is not her natural skin color; rather, it’s a stain from her years enslaved at an indigo-processing plant, which means she is one of the older women. But she is, in effect, every Black woman carrying the weight of her past.

Indigo is an associative color in Daughters of the Dust in the sense that it carries particular meaning throughout. In a 1993 Sight & Sound interview with Karen Alexander, Dash explained, “The color, which is in the bow in [the Unborn Child’s] hair and on the hands of the ancestor, is my way of signifying slavery, as opposed to whip marks or scars, images which have lost their power. […] The color is a trace like a scar.”

It adds layers of meaning to the image, one reading being that the older, dyed hands are the passages through which younger passion and energy are ushered through to create change, a new home, a revitalized endurance, and an existence free of pointed oppression and degradation.

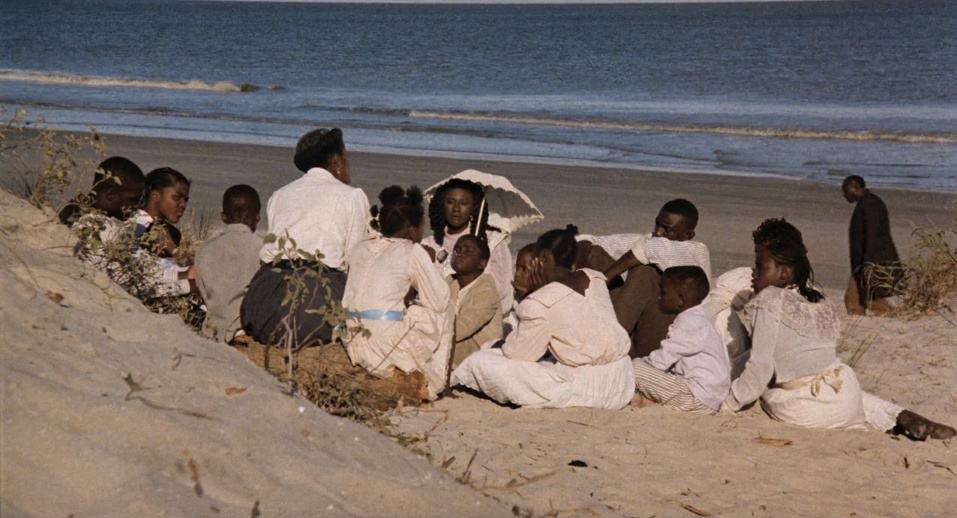

The image of different Peazants resting, learning, and communing in the sand is one of the more common images of Daughters of the Dust, though it’s no less alluring for it. “The camera-work stresses the communal […] Space is shared, and the space (capaciousness) is gorgeous,” writes Toni Cade Bambara, one of Dash’s greatest creative influences.

Of course, the first thing you’ll notice is the baby blue ribbon wrapped around one of the daughters’ waists. Like the blue bow in the Unborn Child’s hair referenced above, it is visual memory, a reminder of the colonialism that ravished them.

Grass pokes out from expansive sand and the eternal ocean crashes softly in the distance, but the eye is drawn to the costumes – peach, canary yellow, lavender, and eggshell hues draped over Black bodies and all but blending into each other and the khaki sand. The sand also matches some of the boys’ darker pants and jackets, an adolescent version of the black suits worn by the peripheral men, one of whom can be spotted in the background.

The color theory temptation is to equate the lightness of their clothes with the goodness of their spirit or being, but if Daughters of the Dust asks anything of us, it’s to stop seeing and interpreting the world through the white western patriarchal lens that has dominated and continues to dominate film spectatorship and criticism.

A deeper reading of the color in their clothes is a “corrective history lesson” that hearkens back to the vivacity of the Gullah culture, “an all-but-lost Black aesthetic” as Karen Alexander puts it. She explains, “Hiding or distorting Black people’s history has denied us images of them, and Daughters works powerfully to recover these from the past.”

In this case, it’s not about the meaning behind each color. It’s about the colorfulness in the collective, the radiance of Blackness when severed from the domination of the white imagination. But Dash’s lack of a film career since shows how unwelcome Hollywood is to insurgent imagination. Unfortunately, Alexander’s words are as dire and true in 2020 as they were back then: “What we can hope for instead [of conformity] is the exposure of a sophisticated Black cinema aesthetic to wider audiences.”

In the image, Viola (Cheryl Lynn Bruce) is teaching the children about Christianity. Viola is one of two women, along with Yellow Mary, who returned to the island from the mainland at the beginning of the movie. But unlike Mary and the rest of the women, Viola wears a black skirt. The sharp division in her white blouse and black skirt depicts the division within her.

In Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African American Woman’s Film, writer bell hooks calls Viola “a force of denial, denial of the primal memory.” She goes on to propose that if Viola had it her way, “she would strip the past of all memory and would replace it only with markers of what she takes to be the new civilization. In this way, Christianity becomes a hidden force of colonialism.”

“Uh-huh, exactly,” Dash responds promptly.

One of the more well-known images from Daughters of the Dust is this monochromatic shot of hands cradling dust. The shot bookends the film. When we first see it, we aren’t sure whose hands they are or what is the context. But, when the image returns, with context, and we come to understand that they are Nana’s hands from when she was much younger, touching for the first time the soil she would build her life and family on.

This image is central to the film and one of eight shots Dash chose to showcase from her film in Karen Alexander’s interview. In the captions, Dash writes, “Young Nana, with dust on her hands, is questioning the fertility of the land […] The dust is the past, and Daughters of the Dust means the daughters of the past.”

By creating a monochromatic image in the brown dress and background that match the dust, Dash immerses us in the dust, in the past, in the rootedness of the Peazants in the natural world, though they will soon migrate to urban, industrialized land. Her characters are daughters of the dust in the sense that we are all forged from dust, humanity’s unifying ancestor, as James Baldwin would put it.

But, in another sense and more importantly, they are daughters of their mother’s past, a past that cannot be jettisoned or erased, regardless of the religion or spirituality any of them hold to. Hooks points out the rarity of a film in which dirt is “not seen as another gesture of [Black] burden” but one of fertility and memory. As Nana says, “Ancestors and the womb are one and the same.”

The visualization of the past in the dirt and hands depicts that unity with a languorous charm, the dirt slipping through the cracks of her fingers and lifting off from her palm into the wind with the same unpredictability as the time-hopping narrative structure. The lifelong charge to “remember and recollect” echoes in the image.

The monochromatic color tone also bleeds into scenes like the one pictured above that are more zoomed out, where the lighter costumes blend into the sand to show their oneness with the land and past that serve as their collective memory.

Nana, Yellow Mary, and the youngest, Eula (Alva Rogers) – three different generations of women with wildly different experiences – embrace near the end of the film. Yellow Mary has caused shame in the family for her prostitution on the mainland (“The raping of colored women is as common as fish in the sea,” she says with a gut-wrenchingly casual tone). Nana has just implored everyone to stay, crying out, “How can you leave this soil? This soil? The sweat of our love is in this soil.” And Eula has just begged the community to love Yellow Mary as they love themselves that they might let go of the cross-generational shame that weighs them down (“Let’s live our lives without living in the fold of old wounds.”). Tears cascade on both sides of the screen.

Depending on how one interprets the hues and saturation, the case could be made for calling this a triadic color scheme. Regardless, it’s complex in color, like it is in context. The triadic read focuses on the indigo of Nana’s dress, the golden gleam in their hair, and the green palms in the background. The same indigo that represents suffering in her hands represents suffering in her dress, but this time it is centered to exemplify a shared suffering between them.

All three women carry the sexual trauma of having been raped by white landowners. All of them carry the degradation and oppression of Black womanhood. In representation of the pain, Nana’s face is as sharp as ever. More tears roll down Yellow Mary’s face.

Eula, however, looks out toward the water with a glimmer of hope that’s mirrored in the golden-orange sunlight caught on the horizon of their hair. Orange is often associated with courage, confidence, and success, all of which sit on their heads like a crown in the sunset. And for Eula, it’s the courage and confidence she needs to set off the next morning.

The image also highlights Dash’s choice to zoom in on Black women’s faces (something hooks points out is rare) and use light for “caressing them rather than assaulting them,” as Dash puts it. The gold in Nana’s earring becomes a symbol of prosperity and tradition. And the green palms bring the whole scenario to fruition, representing growth and healing as the three come together ideologically before they part.

It’s a scene — and a film — you’re likely never to forget.

0 comments:

Post a Comment