Summer at Grandpa’s (Hou, 1984).

DB here:

This is another phantom entry I posted as Private for the seminar I’ve been teaching this term. I’ve opened it up for a wider audience because some readers have written to ask for access to the ideas. These are comments based on assigned reading for the course. Just as important, this entry serves as an introduction to a guest post coming up next week from Malcolm Turvey.

An earlier phantom entry, which considers how critics interpret a movie’s themes, intersects with this one. This is no less wonkish than that was.

The course has been an examination of the theory and practice of a particular perspective on studying film, the poetics of cinema. A poetics of any medium tries to study the principles undergirding the craft (technê) of artistic work in that medium. These principles may be explicit rules, or guidelines steering the makers’ decisions. But poetics can also reasonably try to trace how those principles and practices are designed to shape effects on perceivers. (For film, let’s call them spectators, but they of course listen as well as watch.) What are some fruitful ways to think about effects?

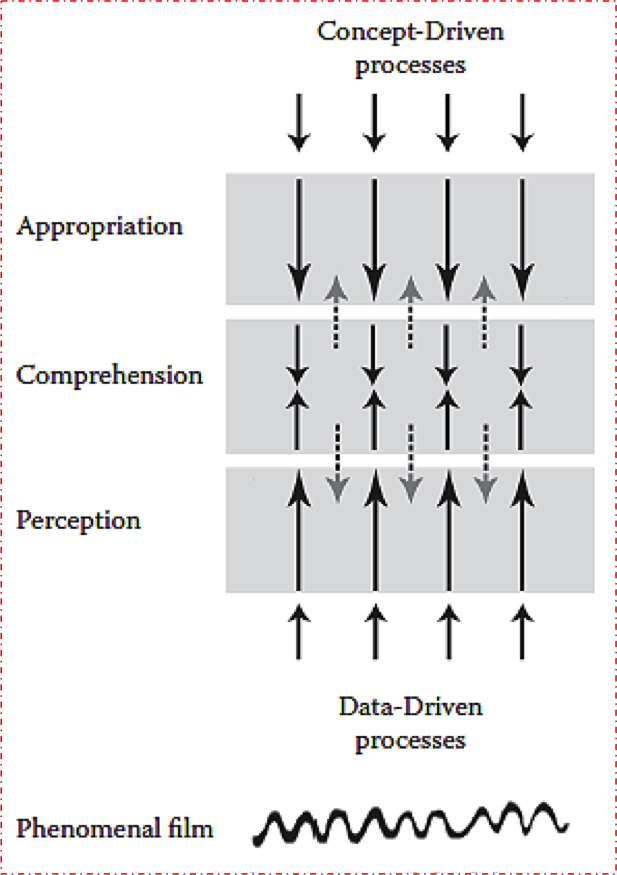

My initial stab at this was the bottom-up/top-down diagram of viewer activity.

To recap: As viewers we have capacities that are data-driven (bottom-up); these yield what we normally call perception. That’s already a huge range of activities, carried out mostly below the level of consciousness. (You can’t watch yourself registering color wavelengths.) In film viewing, perception runs from very fast, encapsulated, specialized, and “dumb” systems, like the phi phenomenon and apparent motion, to somewhat slower (but still fast and involuntary) ones like object recognition, speech recognition, and the like.

The top-down processes, which I called appropriation, are concept-driven, more voluntary, more deliberative, and more extensively funded by experience. A prototypical case would be judging a movie good or bad, or picking a clip to show in class. Interpretation, which I considered in this entry, is a common act of appropriation in the film-viewing community.

In the middle zone are what I called activities of comprehension. A prototypical example is following a story. It’s data-dependent (I can’t make Jackie Chan into James Bond) but it’s also concept-dependent (I can identify the conflicts and combats in a martial-arts film because they make the plot advance in a conventional manner). In non-narrative filmmaking, other comprehension skills come into play, drawing on knowledge bases, heuristics, and the like. You need some experience of art and life to follow the poetic fishing documentary Leviathan.

I wanted to allow feedback too, so the dotted lines in the middle try to suggest how comprehension can fund certain aspects of perception. We recognize Jackie Chan as likely to be the hero, and this concept helps steer our attention to him in his shots. Comprehension of course also funds appropriation, as when after grasping the film’s story we pick it apart in analysis.

One implication, already touched on in the interpretation entry, is this: As we go up from perception to appropriation, the filmmaker’s control wanes and the viewer’s control increases. Spielberg structures Raiders of the Lost Ark the way he wants, but you can appropriate his movie as a piece of imperialist ideology and he can’t do a damn thing about it. In the middle, it’s a negotiation: He steers you to construct the story a certain way, but you can also fill it out with your own inferences, or claim he hasn’t given you enough cues to do so. (Does Marion really love Indy? How much?)

And emotion is involved at all stages of the process, from the jolt of jump scares to the high-level social satisfactions of fandom.

Functions and inferences

Think of all the vending machines you’ve encountered in your life. Each one yielded you those tasty snack treats in a predictable way, but there are different designs and materials. There are those drop-down machines that usually clamp your wrists when you try to reach into their pilfer-proof trenches. There are the little-window ones, which rotate the goodies into place (sometimes). There are even ones that use claws or turntables. And the bits and pieces can be made of plastic or metal, while the gearing and electronics and the machinery for grabbing your money (and denying your change) can be widely varied. But all in all, they have the same basic function and purpose: to take your payment and give you something deliciously unwholesome.

In the same way, my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so. Maybe we should think of the mind as having a core-periphery topography with outward-facing systems (the senses) as discrete modules picking up data while “central systems” supply the top-down treatment. Or maybe the mind is just a tangle of wetware, wires running all over the place, with “higher” functions jammed against, or crisscrossing “lower” ones.

I leave sorting all that out to the experts. But in terms of functions, I think it’s fair to say that most psychologists let the bottom-up/top-down metaphor capture distinct sorts of activities, however they are manifested in our senses, brains, and nervous systems.

More controversial is my argument that these activities are inferential in nature. This signals my commitment to New Look thinking, the early cognitive trend launched by Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Noam Chomsky et al. Computational models of mind emerged from this research. Nobody doubts that in the comprehension and appropriation phases, inferences are involved. Understanding a story or interpreting a movie as sexist clearly relies on inferences, “going beyond the information given.” The tougher controversy comes with perception.

Following Helmholtz, who believed that perception was “unconscious inference,” the information-processing perspective holds that perception is inference-like. It is defeasible. My eyes can fool me, as with mirages and the bent-looking stick in the pond. This is one reason New Look psychology is interested in illusions.

Moreover, perception operates with assumptions, just as inferences do. Many perceptual assumptions may not be learned but rather “innately specified” to some degree–that is, as presets. It seems, for instance, that we are evolutionarily “wired” to expect light to come from above. It’s also very advantageous for us to be able to separate figure from ground and tell living things from nonliving ones. These basic perceptual acts are funded not only by experience but by presets that steer us in a certain direction. No blank slate here; lots of veins and grooves. And given that we enter a structured ecosystem at birth, rich and flexible innate dispositions can be tuned to information pickup during a critical period. Babies learn fast because they’re primed to set the switches.

This perspective is usually contrasted with the view that holds that perception is “direct.” Most famously, J. J Gibson held that “the information is in the light.” Thanks to evolution and our mobility as creatures, we don’t need any elaborate inferential activity. The input is so redundant that we reliably detect the features of the environment automatically.

I think that the Embodied Cognition theorists are somewhat akin to Gibson in their belief in minimally mediated sensory pickup. Admittedly, though, as Gregory Hickok suggests in The Myth of Mirror Neurons, the Embodied Cognitivists do seem to have a computational side in treating mirror neurons as supplying “representations.” And one strain of Embodied Cognition, identified with George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, denies the inferential and computational model but still adheres to conceptual schemes (like metaphors) as representations of bodily experience. So some categorical, mediating inferences seem to play a role.

The next section discusses how New Look thinking can help us understand visual arts. My comments target two essays in the 1973 collection Illusion and Nature and Art: R. L. Gregeory’s “The Confounded Eye” and E. H. Gombrich’s “Illusion and Art.”

Gregory, Gombrich, and art

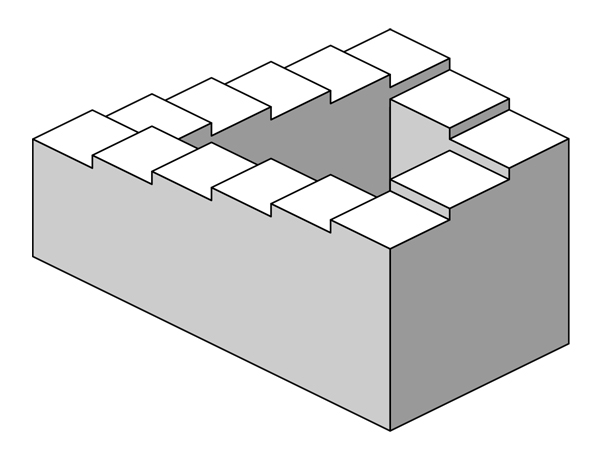

The Penrose steps.

New Look psychologist Sir Richard Gregory (lower right) was a passionate connoisseur of illusions like the Penrose stairsteps. He was famous for pushing the cognitive model of inference-making very far, deep into the basics of perception. He saw perceptions as the usually reliable results of assumptions and hypotheses, in a process significantly similar to what scientists do when they launch hypotheses and check for confirmation. For a career overview, go here.

I take it that he’s trying to answer the question: What perceptual processes generate visual illusions? We evolved to pick up accurate information from the environment, and normally our perception is accurate. The obvious problem with illusions is that they yield false information. What has fooled our eye?

As for perceptual strategies, perhaps in film we could cite special effects and green-screen backgrounds, where perspective, lighting, focus and so on are calculated to suggest space that isn’t really in front of the camera. Our visual system assumes regularities of space that aren’t justified; we usually can’t force ourselves to see these backgrounds as flat.

Some controversies dog Gregory’s theory, chiefly in his reliance on prior experience. He thinks that even pretty low-level outputs depend on knowledge of some sort, if only about our world of discrete edges and solid shapes. He doesn’t seem to treat evolution as shaping many of our perceptual proclivities. In this essay “The Confounded Eye,” he appeals to classical conditioning (p. 66) to get the system off the ground.

But crucial are the ideas we also find in the work of E. H. Gombrich. Gregory assumes an active perceiver, one who takes fragmentary stimuli as cues for building up a perceptual conclusion, through a process of hypothesis-testing. Expectation, assumptions, and probabilities all play a role. Perception is inferential because it can be wrong.

In addition, Gregory reminds us of the importance of habituation (sometimes confusingly called “adaptation”). This means simply resetting the threshold of your sensory input. At first the coffee shop seems noisy, but soon enough you’re paying no attention to it and completely sensitive to your partner’s whisper. People can even adjust to wearing eyeglasses that turn the world upside down! Habituation is perhaps the most robust finding in all of psychology—and something that, when it becomes all-powerful, Victor Shklovsky deplores. (“Habitualization devours works, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war.”)

Gregory’s last book, the cleverly titled Seeing through Illusions (2009), published a year before his death, is a detailed expansion of these ideas. He classifies dozens of illusions according to a richer scheme than the one laid out in his 1973 article.

There’s a lot more in Gregory’s essay, not least the homunculus argument which has been broached against a lot of cognitive theorizing (mine included). But now let’s look at Gombrich’s essay “Illusion and Art.” He was a friend of Gregory’s and he borrowed heavily from New Look psychology.

Despite the book’s title, Gombrich’s magnum opus Art and Illusion doesn’t center on illusion as such. In trying to answer the question Why does [European representational] art have a history? he had to confront “illusionistic” styles, but that issue was secondary to the larger issue of continuity and change in representational traditions. So with an essay called “Illusion and Art,” Gombrich offers a more explicit and careful account of illusion.

I take it that his guiding research question is something like How may we explain the artistic and psychological processes that generate illusion in the visual arts? Not surprisingly, he will make use of some of Gregory’s ideas.

What seem to me crucial here are Gombrich’s reflections on animal perception. Far more than in A & I, he posits a continuum of sensory appeals and so a sort of spectrum of degrees of illusion. To a considerable degree, he has turned my vertical diagram into a horizontal one.

There are automatic, involuntary processes he calls “sensory triggers.” Moving along the spectrum, there are more elaborate strategies for conjuring up illusion, but these will rely on more deliberative processes. Throughout, we never lose the sense that we are watching a representation, however realistic it looks.

Moreover, Gombrich attributes the fast and mandatory illusions, the ones Plato called “lower reaches of the soul,” to evolution. He posits that just like other creatures, we have sensory systems that respond to “triggers” automatically, and sometimes we can be deceived–as predators are fooled by the camouflage of their prey.

So what about illusions? At one end is pure delusion, as with say counterfeit money. Trompe l’oeil is a little further along; you really have to get close to detect the difference. Flat objects, like letters tacked to a board, are good for this trickery, as are fictitious postage stamps like those of Donald Evans.

These cues are very realistic, but crucially the trigger need not be a close replica of what it represents. Approximation can work. The duckling can follow a moving brown box if it moseys like its mother; the box doesn’t look like Mom, it just triggers the Mom-response. Stickleback fish will strike a red cloth that doesn’t look much like another fish’s belly–except in being a moving patch of red. Recall as well the Frog Multiplex. These critters are slaves to innate “action programs.”

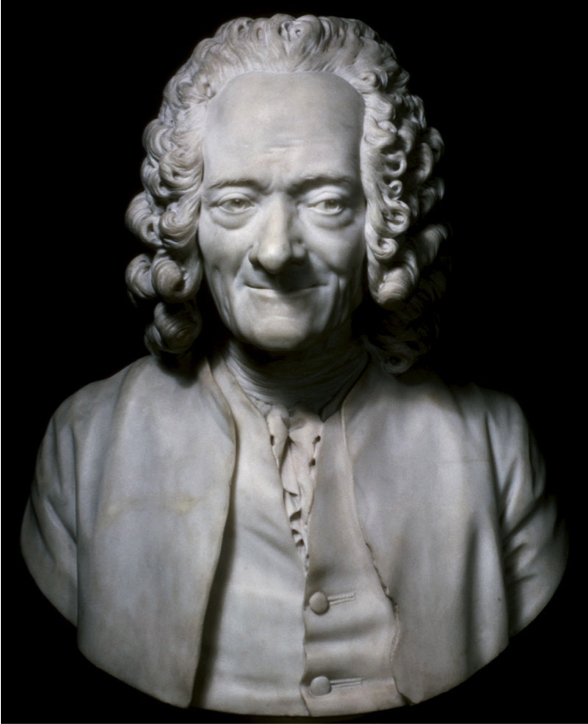

A flat, impoverished display of a wiggling worm is enough to get the right (wrong) reaction. And note a fascinating Gombrich example, Houdon’s bust of Voltaire, where the sparkle in the eye is actually a tiny lump protruding from the surface. You couldn’t get farther from a non-realistic device for depicting a gleam of light.

Hence a typical Gombrich formulation: What matters most is stimulation, not simulation. Images at whatever degree of realism rely on key features that trigger our automatic systems. The big transaction isn’t resemblance. The link is not between image and object but between the activities involved in processing the image and those processing the object. The image has hitched a free ride on perceptual habits, or faults, that we already have and cannot always see beyond.

Further along the spectrum, our response can be more flexible, less data-driven. We can learn to control and use the illusion, appreciating it. We can consciously factor in context, prior experience, interpretative possibilities. We can shift mental sets and adjust our expectations, we can test projections by trial and error. We’re now in my realms of comprehension and appropriation–comparatively self-conscious film experiences. But we couldn’t go so far and wide without anchoring our response in the fast, mandatory “lower reaches of the soul,” whose powers derive from evolution.

Gombrich’s essay also emphasizes time more than Art and Illusion had. The sequential nature of perceptual activity–scanning an image–doesn’t occupy him much, but I think it’s quite important. I’ll give an example later on. But he’s right to stress the pressure of time in an evolutionary context. Fight-or-flight decisions have to be made fast, and so creatures with oversensitive mechanisms had a better chance of surviving, even if they sometimes wasted effort in avoiding harmless things. This time dimension takes Gombrich to movies, of course, as well as to flight simulators.

The last main point I’d stress is Gombrich’s insistence that we’re always after meaning. In Art and Illusion he proposes that we never see space as such, but rather medium-size objects in an environment. Representing “space” is tough, but people can provide convincing information about the spatial layout of people, places, and things. Mapmakers do it, technical illustrators do it, we make stabs at it, and painters do it with precision, delicacy, and force. Ditto textures, lighting, and other features of the world.

The “effort after meaning” flows from the inferential, seeking nature of perception. In a memorable formulation Gombrich says we don’t see people’s eyes as such: “We see them looking.” We are geared to meaningful objects, actions, and implications, not purely physical metrics. Again, this makes evolutionary sense. Creatures who focus on measuring the distance between a tiger’s eyes aren’t going to leave as many offspring as creatures sensitive to gaze direction and threatening sounds.

Perceptual psychologists will debate whether the New Look/inferential model or the Direct Perception model of Gibson et al. is better for explaining real-life perception. But as my concerns are in studying art, particularly cinema, I think the inferential perspective is better suited to analyze what concerns me. For one thing, it grants that grasping art is active and skilled, something that I think we all acknowledge. Your and my skills of noticing, understanding, and responding complement the skills of the ‘poet’ or maker. We complete the artwork.

Moreover, artworks offer simplified, streamlined displays very different from the blooming, buzzing confusion of the world. Gibson’s perceiver has to hack through a lot of distractions to extract the texture gradients and optical flow that will specify the layout. Art works already do that for us. Art works, films included, are designed with precision to trip our inferential engines at all levels. As a result, an inferential model tracks more closely the critical analysis we want to conduct on films. I’ll try to give two examples at the end.

A personal detour: Monkey see, David do

The Chinese Feast (Tsui Hark, 1995).

In the 1980s, as I was studying narrative and style in Hollywood films, I was struck by the ways in which the films’ designs seemed to aim for particular responses from spectators. I wondered whether the norms in place were coaxing us to perform particular mental acts: assuming, trusting, hypothesizing, anticipating, and so on. A lot of what we see and hear in a film sets up “intrinsic norms” that in effect teach us how to comprehend the story.

This led me to float an approach to spectatorship based on then-current premises of cognitive psychology. I tried to work it out in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and later work. Other researchers found this intriguing (to use a Kristin word) and developed well beyond it. Over the years an entire subfield emerged, with its own journal, conferences, and academic network.

The psychological findings I found most useful for my research questions were rather robust, well-confirmed ones involving informal reasoning: the use of schemas, heuristics (quick and dirty inferential routines), prototypes, and other concepts. I call these findings robust because they’re fairly well-replicated phenomena that different theoretical paradigms have tried to explain. They’re especially useful tools for us as students of the arts, for they bear directly on matters of narrative–plot, characterization, causal connections, and the like. They map fairly comfortably onto our analytical categories.

The broad point is that just as visual illusions exploit deficits in our visual system, narrative often plays to biases and shortcuts in more elaborated inferences. We’re good at tracking cause and effect, but the principles we use are “folk psychology,” not the principles of physics. In real life, we may attribute Oscar’s grumpiness to his just having a bad day, but Oscar is a film character and is introduced to us grumpy, we’re inclined to take him as a permanent grouch. (This is called the fundamental attribution error.) This example also trades on the primacy effect, also known as anchoring, which lets the first instance we encounter shape our pickup of information encountered later.

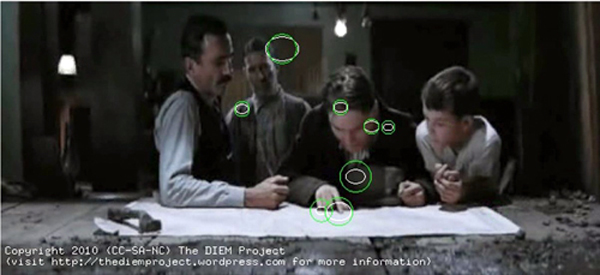

A prime instance of a robust finding was research into eye-tracking.

Film theorists have long considered that attention is central to filmic effects. Once eye-tracking devices became easy to use, researchers could use them to study how people scanned movie images. The pioneering work here was done by Tim Smith. I survey the research program here, and Tim did a powerful guest blog to follow up. His entry, probably the most popular post we ever had, earned him press coverage and a guest visit to film companies to present his research!

For more discussion of these middle-level findings, you can see this reader-friendly version.

Many of these activities are accessible to us, if only in retrospect. In following a narrative, if we pause the movie, we can think about what we’ve noticed and what we expect. As the years went by, though, I began to realize that probably a lot of what engaged us in films wasn’t so easy to tap consciously. Plato’s “lower reaches of the soul” invoked by Gombrich played an important role.

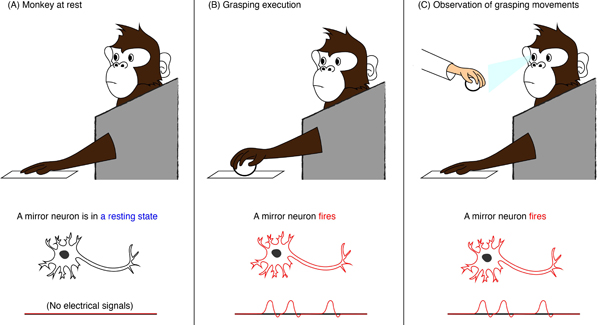

So in the 2000s, when research into mirror neurons was emerging, I drew two lessons. One was that certain primates could respond to film images much as we do–recognize objects, track movements, and so on. I thought, and still think, that this is an exciting piece of information. What was methodology for the researchers is a substantive finding for us. If macaques can recognize what a movie shows, it’s hard to argue that pickup depends on cultural codes.

Second, I thought that the prospect of mirror neurons held promise for carrying inference/computation down into the wiring level. Given all the presets supplied by evolution, isn’t it conceivable that social primates may have evolved to “resonate” to actions, expressions, and even emotions displayed by their conspecifics? It would be another part of a natural endowment that, suitably tuned by the social environment during the critical period of growth, could bootstrap a broader set of skills–such as following stories.

Hence the remarks I made in my 2008 “Poetics of Cinema” essay, where I took the view that “it seems we have a powerful, dedicated system moving swiftly from the perception of action to empathic mind-reading.”

Fairly soon mirror neurons became absorbed into a larger trend toward neuroscientific examination of film viewing. I’m not sufficiently expert to appraise that work, but I do have thoughts about what it can, and can’t, tell us about understanding film.

Mirror, mirror in your head

As I understand it, the Embodied Cognition research program aims to answer this sort of question: What role do automatic, low-level visual processes play in enabling spectators to respond to film? More specifically, do the processes enable us to understand and empathize with action, agents’ intentions, and agents’ emotional states? I think that the general answer proposed is yes.

Mirror neurons play a role in this process. They were first discovered in macaque monkeys, and there is some evidence that they exist in humans. The hypothesis is that when we see a piece of action, in life or in cinema, we spontaneously mimic, in the pattern of cell firings in our brain tissue, the sensory and motor processes that create it. Our brain mimics or “resonates with” the action we perceive. We don’t just “understand” that the man is lifting a glass; in a weakened form we are repeating the experience of his doing so. Of course we may not be holding a glass, but to a degree the sensory and motor cells in our brain tissue rehearse the lifting gesture. Because we’ve executed similar actions, the cell firings are marked out through electrochemical patterns.

This argument takes us into the specialized areas of brain science. A useful account of the general scientific debate is here. The appended articles quickly turn technical, though. An easier read is this piece in Wired. For film, the fullest account of this view is provided by Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra in their recent book, The Empathic Screen: Cinema and Neuroscience.

In our next blog entry, a guest post, Malcolm Turvey will offer an analysis and critique of that book’s arguments. As a pendant to that, I’m just going to signal my reservations about the project and its results. In the last section of this entry I also want to make a point that Malcolm will explore conceptually: How much specificity does a “psychology of cinema” need for us to say useful and unusual things about film?

My first general comment: What the authors mean by understanding, or “involvement,” or the “from the inside” part of experience could do with more specifying. Malcolm will explore this question in detail. In addition, I wonder whether concepts like “identification” and “immersion” fruitfully characterize our engagement with all films, or even those we find exciting.

Camera movement occupies a privileged place in Gallese and Guerra’s scheme. “The involvement of the average spectator is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” Yet what about the first thirty years of cinema, in which camera movement is quite rare? Tableau cinema, as discussed in many entries hereabouts, was presumably quite effective in moving audiences. If camera movement automatically steps up engagement, why didn’t it become more common sooner? And are we talking only about camera movements forward, which are the privileged examples cited from Notorious, The Spiral Staircase, and other 1940s films?

The only effects of the nonmoving camera noted by Gallese and Guerra are expressive ones. “In the absence of movement the editing and arrangement of figures and spaces within a shot can produce a feeling of oppression.” Well, editing and staging within a fixed shot can indeed produce that effect, as we see in Antonioni, but it need not. This makes especially curious the authors’ claim that Dreyer’s La Passion of Jeanne d’Arc, with its close-ups, is a static film evoking through editing “the violent shades of power and persecution.” But of course from start to finish Jeanne d’Arc contains many camera movements.

And are we to assume a “progressivist” conception of history, so that the Steadicam is a step toward “better” (=more engaging) filmmaking? Would all those spectators aroused by crosscut last-minute rescues, from Griffith to Black Panther, have been even more carried away if there had been more camera movements?

Gallese and Guerra don’t assert that every shot would be improved, immersion-wise, by adding camera movement. We also need, they claim, more calm and stable orienting shots so that camera movements can create “peak moments” for maximum impact. Yet, to revert to their favorite director, Hitchcock created quite a peak moment in a certain shower scene wholly through editing. Again, would a flurry of camera movements have made it even more visceral? In fact, the leave-taking camera movement that ends this scene serves as the calm after the perceptual onslaught of cuts.

Of course Gallese and Guerra realize that camera movements aren’t the be-all and end-all of cinematic technique. Yet their discussion of editing seems to me rather unrevealing. Their experiment in varying camera angle through cutting yields the conclusions that “we use the same processes that we employ in our visual perception of the real world” and that our brains register violations of continuity rules to some degree. I am not surprised, though it’s good to have confirmation.

Malcolm will take up several other areas of inquiry in his followup entry. I want to end with a couple of examples to set us thinking about the difference between the neuroscientific arguments and those from a poetics perspective. Here’s a chance to weigh research questions against one another, to see the sort of ideas and information each can yield.

Direction and misdirection: Delicacy via precision

Let’s ask a poetics-weighted question: How can viewers understand the construction of shots designed for perceptual force and narrative comprehension? At the least, we should expect that the pictorial design will solicit attention and emphasis. Deploying these ideas enables us to talk about deflected attention and gradation of emphasis. And we need not assume that the camera is a surrogate for us.

In Summer at Grandpa’s, Hou Hsiao-hsien gives us a somewhat episodic tale of kids sent to live with their grandparents while their mother is hospitalized. In the village they play with the local children and have minor brushups with their stiff grandfather. They’re exposed to aspects of life and death that the modern city has shielded them from. One of those is a madwoman who wanders through the countryside keening.

The boys won’t play with the little girl Ting Ting. So, bearing the toy fan she always carries, she wanders to the railroad tracks and stumbles in the path of a train.

The madwoman’s rescue of Ting Ting is a harrowing, gripping moment. (No need to be energized by camera movement.) The pounding rush of the train, very loud, is an assault on us. The narrowness of her escape is emphasized by glimpses of the two huddling on the other side of the tracks. No need for camera movement to amp up this jolting moment.

But Hou has introduced something else, the fallen fan that tips over and just barely escapes being crushed by the train wheels. Its childishness–pink and orange and green, tipped over by the rush of the wheels–is a kind of stand-in for Ting Ting. It also, by virtue of color and the absence of anything else to look at, rivets our attention.

No less striking is this: When the train has passed, the fan’s blades reverse direction and spin the other way! This tiny bit of movement, visible on a big screen if not here in miniature, provides a kind of coda for the shocking action. This exemplifies, for me, Gombrich’s “visual discovery through art.” We see wind power in miniature, in a natural experiment in the sheer physics of a situation.

All of which proceeds from careful craft decisions. Hou has stretched the norms of framing and staging in fresh ways to achieve a powerful effect. Nothing I see in the mirror-neurons story could address, much less functionally explain, what’s on display here.

Similarly, the Embodied Cognitivist position seems to me too coarse-grained to capture the rather different range of artistic effects in a sequence from River of No Return. Matt Calder and his son Mark help rescue Kay and Harry from their clumsy efforts to raft their way to town. Preminger films the rescue in shots that exploit the CinemaScope ratio. Many critics have noticed how Kay’s wicker trunk of clothes falls into the current and remains visible far into the distance as the dialogue in the foreground develops.

Since the arc of Kay’s character traces the gradual stripping away of her past life as a dance-hall entertainer, this phase of her change is made visible in a soft-pedaled way. Attention and emphasis are played down. Preminger prepares us to watch for secondary and tertiary areas of importance–what Charles Barr has called gradations of emphasis. Alert viewers may notice the drifting basket, others not, but for those who do some inferences will be forthcoming. For one thing, What might be the significance of this basket?

Turns out that this was practice for using our eyes. Having prepped us at the riverside, Preminger again plays with graded emphasis. Before the rescue scene, Matt and Mark share coffee before going out for target practice.

Few of us will notice the rifle in its long holster there on the back wall until Matt takes it down.

Now compare this later scene.

Sparse as it looks, the main shot is busy. The men were decoys but the holster was waiting there to be used at just the right moment. We could have noticed it at any time. Maybe some folks did.

When the rifle pokes into the shot, stressed by Harry’s line, it probably surprises us. But those of us who may have noticed the empty holster earlier may experience suspense rather than surprise: Where did the gun go? We have to wait and see.

This sort of multilayered visual effect seems to lie beyond the sort of responses that G & G attribute to aggressive camera movements. We may not be “immersed,” but we are definitely engaged–albeit coolly. The image is a visual display we search, not a space we imagine ourselves interacting with.

You may say that this sequence is so atypical it’s unfair to use it as a counterexample. But I think it’s just an extreme instance of what filmmakers are doing all the time. Preminger uses classic cues: the holster is isolated, it’s sitting near the center of the picture format, and it’s well-lit. On the big screen in a 1954 movie house, it would be very evident, in principle. And we’ve seen it used before in a very similar camera setup.

But Preminger has steered us away from what’s important by creating competing centers of attention. There are the men’s faces and gestures, the words spoken the dynamically unfolding drama, the woman and the boy executing repetitive actions (what Gombrich in Art and Illusion calls the “etc.,” take-as-read principle). Attention and emphasis are led by lines of least resistance; you’d have to be pretty stubborn to study that holster.

Of course there is a neurological story behind attention and eye tracking. And perhaps Matt’s gesture of reaching and seizing the rifle may “resonate” with our neural circuitry. But for the artistic effect Preminger prompts, it’s surely less salient than our acts of following, scanning, noticing, and registering all that’s going on in this misleadingly muted visual, auditory, and dramatic array. Our neural circuitry isn’t available to us for inspection, but we can bring to awareness the way that directors direct–direct our attention, weight various areas of the shot–usually to supply information, sometimes to suppress it.

In bringing this scene’s constant flow of information and withholding to light, we’re homing in on an uncommon but precise craft decision that has distinct artistic effects on us. This is, I think, an instance of analytical poetics–analyzing a particular film by using the norms and practices we reconstruct on the basis of historical research.

I lay my cards on the table. If our research question asks about the fine-grained principles of cinematic craft, its creation and consequences, its norms and options, we are likely to have little need for generalizations about how all traveling shots may mimic cell firings. Functional explanations can be enlightening when we don’t know about the mechanics. We can attend to precise, often delicate, effects as results of weighted choices from a historically available menu of options. After all, artists are achieving these effects in other media. Even if neuroscientists don’t care about these things, filmmakers do. We should.

So much other bibliography I could suggest! Good introductory overviews are Michael Morgan, The Space between Our Ears: How he Brain Represents Visual Space (2003) and Jennifer M. Groh, Making Space: How the Brain Knows Where Things Are (2014). Both have clear, nontechnical accounts of fascinating experiments. More advanced, but a trailblazing study, is Jerry Fodor’s The Modularity of Mind (1983), a fun read.

I hijack the Frog Multiplex for a discussion of cinematic coding. For more on gradation of emphasis, see this long-ago entry in homage to Charles Barr. I discuss ‘Scope aesthetics from the standpoint of poetics in this online video. I consider Hou’s staging strategies in my book, Figures Traced in Light.

During the current health crisis, Berghahn has made all issues of Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind freely available. Several articles over the years debate issues around cognitive film theory and brain-based explanations of media effects. My version of cognitivism is discussed in the June 2016 issue. For still more, there’s this web essay and this broad overview.

Inception (2010).

0 comments:

Post a Comment