Growing up: we all do it. No two people have exactly the same coming-of-age story, yet more often than not, we’re drawn to many the same youth-centered stories on screen, deeming them classics and rewatching them again and again. Young people are rarely given the power to tell their own stories, so a coming-of-age film that captures a specific generation, culture, or subculture feels like a rare and special thing for those who are reflected on screen, especially when the film itself finds a viewer during their most formative phase. A good coming-of-age film can become an emblem of sorts, a touchstone that’s at once deeply personal in its description of a fleeting, emotional era of life, and universal in its appeal to anyone who’s lived through it.

The best coming-of-age films mix nostalgic familiarity, impressionistic experiences, and a dollop of brutal honesty that comes with the jarring, often unwelcome understanding of the adult world that accompanies adolescence. That last part is usually handed across time from the more experienced filmmaker to the younger protagonist, a retrospective technique that’s unique to the subgenre and that lends the greatest coming of age stories a sort of prismatic blend of naivety and wisdom.

Although the entries on this list span eight decades, you may notice a significant amount of recent movies. Have coming-of-age films gotten better over time? Maybe not, but American films have certainly begun to reflect the diverse realities of the off-screen world more in recent decades than ever before, so it’s no wonder the best new teen stories each feel honest, unique, and timeless. It’s worth noting that we made the editorial decision to leave off any would-be classics that are too new to look at with any distance, meaning that staff-loved 2019 films like Booksmart and Little Women are excluded from the ranking.

Read on for our list of the best coming-of-age stories of all time, then join us in being grateful to have made it out the other side of adolescence.

50. Ginger Snaps

Getting your period is an oft-examined topic in the horror genre. The body bleeds and the body changes, making it the perfect vehicle for body horror. The transformation of the female body has also lent itself to creature features, as what cultural critic Barbara Creed calls “the monstrous-feminine” cannot possibly be perceived in the human body. Enter Ginger Snaps, a werewolf movie about Brigitte (Emily Perkins) an outcast girl who must figure out how to cure her sister Ginger’s (Katharine Isabel) lycanthropy. Not only is this a film about the unruly female body, but it is also about sisterhood and trying to stand by your ideals as you grow up. Your period isn’t the only weird thing you have to deal with as a teenager; it’s also about recognizing what you believe in and what’s worth fighting for.

Isabel is the werewolf sister who oozes the kind of sexuality we all wish we had in high school. Her transformation from goth outcast to the hottest girl in school is a narrative many of us weirdos wished we could achieve, though there is obviously a massive cost. Plus, Ginger Snaps features one of the best werewolf designs of the horror genre. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

49. Daisies

Sometimes growing up means recognizing just how selfish the world can be. Such is the case for Marie I (Jitka Cerhová) and Marie II (Ivana Karbanová) in Vera Chytilová’s 1966 film, Daisies. Chytilova was a seminal director in the Czech New Wave, an experimental film movement where filmmakers from Czechoslovakia experimented with narrative, particularly in the name of politics. Chytilova did just that with Daisies. These two young girls recognize the world is spoiled, so they decide they want to be spoiled, too. They stuff their faces, tease men, and reject the common ideas of femininity. They do not wish to be like everyone else. The Maries want to be themselves and discover how they wish to navigate the world. In the process, they get a little messy but have a lot of fun doing it.

Using the absurdist film techniques that characterize the Czech New Wave, Chytilova creates a nonlinear coming of age story that refuses to give any kind of narrative satisfaction. The satisfaction and joy lie within two young women who realize that they don’t have to be what society wants them to be. (Mary Beth McAndrews)

48. The Perks of Being a Wallflower

The feeling of the air on your face during a night drive, your license still new enough to burn a hold in your pocket. The magic of hearing a song on the radio that for just a moment feels like it was made for you alone. The brick-by-brick formation of self and community that takes place in high school: a journal all your own there, a spontaneous Rocky Horror Picture Show performance here, a first kiss and a pot brownie to top it off.

These are the youthful experiences that make up The Perks of Being A Wallflower, but there’s an undercurrent of darker themes, too: suffocating anxiety, paralyzing awkwardness, the acute pain of trauma realized. Each of the three protagonists of Stephen Chbosky’s book-turned-film is wrapped up in a personal struggle and each deals with it differently. Sam (Emma Watson) pursues men who treat her poorly because she doesn’t think she deserves love, Patrick (scene-stealing Ezra Miller) buries the pain of homophobia under a flamboyant exterior, and Charlie (Logan Lerman) is plagued by depression and intrusive thoughts that keep him from fully experiencing typical teen life. Perks does the hard work of looking closely and earnestly at teen life, not only the triumphant highs but also the lows that must be bravely overcome. “We could be heroes,” as the Bowie song says, “Just for one day.” (Valerie Ettenhofer)

47. Boy

When you’re a kid, idolizing at least one of your parents is practically the default. This is especially true for Boy (James Rolleston), a Maori pre-teen who elevates his absent father to mythical proportions. When his dad Alamein (writer-director Taika Waititi) finally returns, Boy and his silent younger brother Rocky (Te Aho Aho Eketone-Whitu) have to reconcile the Shogun warrior/king of pop/superhero they imagined with the obvious shortcomings of the impulsive, selfish, relentlessly human man in front of them.

Boy is Waititi’s most serious film, and also his most personal. It was filmed in Waihau Bay, New Zealand, the place where the filmmaker grew up, and although it’s got an imaginative undercurrent, Boy also has a verisimilitude that blends impressively with its more creative elements. Boy is for anyone who ever had to realize that their dad was just another person, but it’s also for anyone who grew up in a neighborhood with tons of kids and seemingly no parents, with broken down cars in the backyard and sticks for toys. Boy and his friends are on the precipice of discovering everything they don’t have, and it’s clear that the protagonist’s playfulness could curdle into rage or sorrow at any moment. In the end, it’s not his father but himself who Boy must imagine a version of that he can live with. (Valerie Ettenhofer)

46. Picnic at Hanging Rock

A supernatural mystery, an exploration of adolescent power and obedience, and an unrequited queer love story wrapped up in one ineffable story, Picnic at Hanging Rock lives in its own genre. There are numerous characters to which a young viewer can connect: the beautiful, commanding Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert); the awkward Edith (Christine Schuler); the traumatized Irma (Karen Robson); or the outcast Sara (Margaret Nelson).

While Sara gets most of the screen-time, Peter Weir’s film is about all of them and their growth through and after the enigmatic disappearance of four people. It’s incredibly elegant in style, but there’s more substance tucked away in the glances and gestures of these girls than initially meets the eye. It’s an incredible, horrifying film that is much less invested in satisfying an audience when, instead, it could linger under your skin and stay there. (Cyrus Cohen)

45. Aparajito

Grouped together, the Apu trilogy of films by Indian master filmmaker Satyajit Ray form one of the greatest cinematic coming-of-age narratives of all time. But we can’t really name all three for one slot, and unfortunately, they’re not each popular enough to take up three spots on this list either. The greatest and most famous of the three, Pather Panchali, leans a little too young on its own to count as a coming-of-age film and take the single representative of the series, so Aparajito stands in.

In the middle installment, which is based on the end of Bibhutibhushan Bannerjee’s novel Pather Panchali and the beginning third of the follow-up, Aparajito, Apu (Smaran Ghosal) loses more of his family members and begins to learn to live on his own. First, once he becomes a teenager, he receives a scholarship to study in the big city of Kolkata, then he also begins working to keep afloat there. To complete his transition from childhood, his mother dies at the end, leading to part three, The World of Apu, to follow him as an adult. (Christopher Thompson)

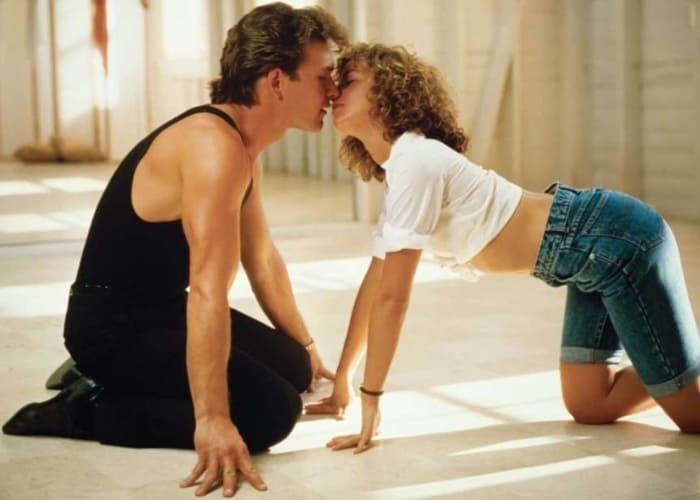

44. Dirty Dancing

Dirty Dancing calls its shot in the coming-of-age canon with Johnny Castle’s famous line “Nobody puts Baby in a corner.” The film watches Francis “Baby” Houseman (Jennifer Grey) grow up over the course of a summertime family trip to the Catskills. When she meets dance instructor Johnny, played iconically by Patrick Swayze, Baby realizes just how small her world has been. Johnny introduces her to a world of dance, sex, and complicated adult decision-making. Dirty Dancing has a lot of dirty dancing and makes great use of its ‘60s setting to soundtrack the film with mambo and Motown galore.

The masterstroke of this film is that it’s not a dynamic where Castle takes a naive, inexperienced young woman and sexes her up exclusively for his purposes (looking at you, Grease). Instead, Castle helps Baby realize that she’s capable of much more than anyone expects of her. Baby is able to embrace her sexuality along with her intelligence and ability. As far as coming-of-age romance stories go, Dirty Dancing remains a relatively early example of a relationship built on mutual trust, equal agency, and personal change for the better. (Margaret Pereira)

43. Boyhood

Boyhood is one of the few films on this list in which you quite literally watch its characters grow up and come of age. Filmed over a 12 year period by maestro Richard Linklater — a director reputed for his warm, nostalgic depictions of the passage of time — the movie is an astounding documentation of the lapsing years in Mason Evans’ (Ellar Coltrane) life, especially the wax and wane of his relationships with mom Olivia (Patricia Arquette) and dad Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke). The film’s success is rooted in its attentiveness to life’s smaller moments; we don’t get to see the graduation ceremony or the divorce proceedings, but we don’t need to. Boyhood is an ode to the nooks and crannies of an ordinary life — and sometimes that’s all you need for an extraordinary movie. (Jenna Benchetrit)

42. Marie Antoinette

It might not be a growing up experience we’ll ever go through, but the playful historical fiction feels supremely relatable in the hands of writer-director Sofia Coppola. She can fashion Kirsten Dunst, her career muse, in extravagant dresses, shower her with ungodly amounts of attention, and drown her in luxury while preserving the well-tread deafening silence of a first romantic encounter, or a reticence around adults, or a cute innocence that expires at a certain age. After all, Antoinette is 14 when we meet her, swooning at the possibility of love (Jason Schwartzman perfectly cast as the awkward boyfriend/heir to the French throne) and lavish living for the rest of her life, before she has children and tragedy starts to set in. It’s through coming-of-age stories like this one that we get a glimpse of the threads of universality that sew growing pains and discomforts in adolescence. (Luke Hicks)

41. Raw

The French New Extremity as a subgenre is all about, well, being extreme. Its films are bloody, gory, and nihilistic as the human body seems to fall apart at the seams. They often focus on the torture of the female body and watching a female character writhe in turmoil. Julia Ducournau’s Raw is all of that but more. She takes a borderline exploitative subgenre and makes it a cannibalistic feminist coming-of-age story where female rage is taken seriously.

Justine (Garance Marillier) is sixteen years old and heading to vet school. There she is forced to consume raw meat which awakens something animalistic in her. Suddenly, she is embracing the rage that has always been bubbling inside of her. She begins to consume human flesh in increasingly larger amounts. Raw is deliciously disgusting, a film that lets its female characters be gross within painting them as monsters. Coming of age is messy and full of anger, so why not portray it that way? (Mary Beth McAndrews)

0 comments:

Post a Comment