Happy New Year 2020. We’re two months into the future that Blade Runner promised, and I’m damn disappointed that we’re not all piloting to work in our Spinners. Forty years ago, the fictional flying car felt like a certainty. So did our dystopian present, but it would be nice to nab a bird’s eye view of the hellscape below. If we don’t get above the asphalt in my lifetime, and all that sci-fi fantasies delivered on were Boston Dynamics robodogs and water-propelled jet packs, then I’ll be planted in my grave with a pair of very stern, crossed arms. I still believe in Syd Mead.

The visual futurist was a dream-weaver. As a kid, he was reared on the pulps, diving into the worlds of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. More importantly, Mead lost himself within the covers that wrapped the tales, featuring the brilliant architecture of Hugo Gernsback. There he saw a future in radical contrast to the Great Depression and World War he was born into. There he saw hope and a humanity that pursued knowledge over devastation, spaceways over breadlines. His gift would be to continue in that bright tradition.

After spending a little time in the army, Mead sharpened his skills at ArtCenter (then known as the Art Center College). He was almost immediately recruited by the Ford Motor Company in 1959 and placed inside their Advanced Styling Studio. Mead was in his element, amongst the likeminded, free from the constraints of reality, and designing cars powered by unknown propulsion systems. While operating in the early stages of development, Mead and his cohorts were given total freedom of expression, and the results were vehicles destined to populate cinema.

Mead’s work in Detroit would eventually land him jobs with United States Steel, Allis-Charmers Machinery, 3D International, and Phillips Electronics. His vision gained a reputation, and by the 1970s, his artwork was touring across Europe and gaining attention in Hollywood. The studios who regularly pilfered concepts from automobile shows didn’t just see exceptional fantasy with Mead — they saw his reality.

In 1979, John Dykstra, the special photographic effects supervisor on Star Trek: The Motion Picture, was in trouble. His director, Robert Wise, was a man of exceptional creativity, but he didn’t necessarily understand the craft required to bring science fiction concepts to life. When the original photographic effects supervisor, Robert Abel, was fired because Wise bucked against his computer-graphics-driven process, Dykstra was brought on board. Starting nearly from scratch, with half the time to complete production, Dykstra needed access to a strong, immediate vision. Syd Mead was his man.

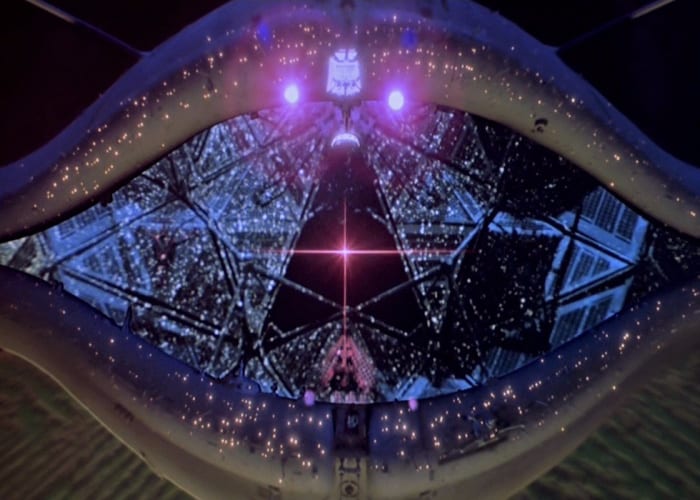

Mead was given the task of realizing the central threat of the film: V’ger. In the story, the massive space vessel is on a collision trajectory with Earth, and any starship that crosses its path is decimated by a “twelfth-power energy field.” The structure is ridiculously immense, an AI metropolis with a NASA satellite at its core. Mead was also confined in his design due to a gargantuan, six-sided rotating aperture model that had already been built by the previous team and had to be used because money was spent. Mead plopped the space-vent in the middle of his concept and worked outward like spokes on a wheel.

At the time, Hollywood was just another industry to dominate. Mead was primarily living in Holland during Star Trek‘s production, cranking out blueprints for toasters and video recorders during the day and V’ger sketches by night. He was not a Trekkie, but he was the product of the same optimism that spawned Trekkies. With his foot in the door, other artists recognized his artistic foresight and came calling.

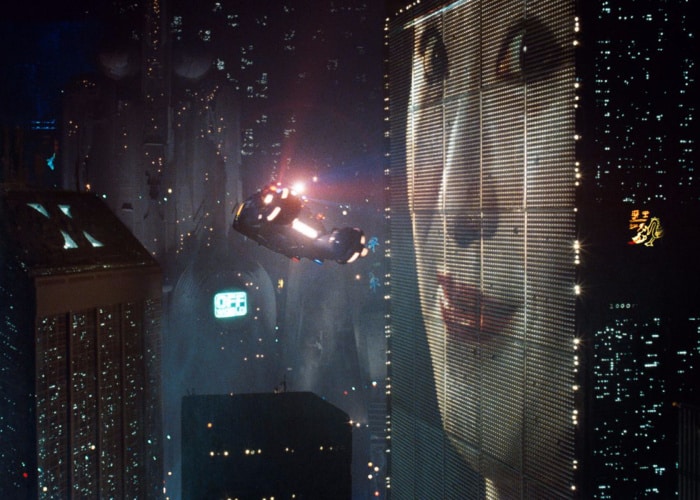

Ridley Scott was next. He was initially brought on board to design only the cars, but when the director saw Mead’s painted backdrops for the Spinners, he demanded that the artist take over the rest of Blade Runner‘s aesthetic. The city came out of the sleek yet sharp cut of the vehicles. As he did with the cars, Mead operated through the process of retrofitting, building bobs and whistles atop designs until they appeared functional.

Mead called the world of Blade Runner “retrodeco” or “trash chic.” All the instruments, whether they are cars, rooms, or garbage bins, are rooted in the reality of 1980 and only slightly boosted by imagined future-technology. Even the flying car was thoroughly considered and theorized from the notion of British harrier jets. The idea was that beneath the Spinner is a turbine that takes in air and redirects the thrust to control the direction of the car. Guys, we can make this happen.

Elon Musk is certainly doing his part. He’s the man with the money that Syd Mead’s creations demand. Musk’s frustrations over landlocked treads and by-the-numbers style emboldened him to launch Tesla’s infamous Cybertruck late last year. Clearly lifted from the brain of Syd Mead, Musk made one helluva statement with his ugly pickup. Form follows function, yes. Also, it’s 2020; the future is here. Let’s deliver on what we were promised. The Cybertruck is his vision board. He’s putting it out there. We’ll be in the air before I’m fertilizer, hopefully.

From Blade Runner, Mead went on to design the light cycles and tanks of TRON, Short Circuit‘s Johnny 5, and numerous other star-worthy vessels in 2010, Aliens, and Mission to Mars. He was a futurist and a dream-weaver, but he never struck imagination without consideration. His toys could work, given time. We’re just waiting on the economics to catch up to his propositions.

On December 30th, Mead died in his Pasadena home after a three year battle with Lymphoma. He was 86 years old. He never saw his flying car, but he got the Cybertruck. He also left us knowing that the future he pictured was the same one we all desperately want to live. His work can be thoroughly lavished and explored in a recent hardcover collection entitled The Movie Art of Syd Mead: Visual Futurist, published by Titan Books. One cannot distinguish the care he took between the realm of Hollywood and Ford Motors. It’s all possible.

0 comments:

Post a Comment