Martin Scorsese‘s The Departed came out in 2006 and did pretty well for itself, picking up four Oscars including those for Best Picture and Best Director (Scorsese’s first). The film, which is about moles planted in both the Massachusetts State Police Department and Boston’s Irish Mob, is orchestral and gritty, and one of Scorsese’s best at-bats. And in case you didn’t know, it’s also a remake of a 2002 Hong Kong action flick Infernal Affairs.

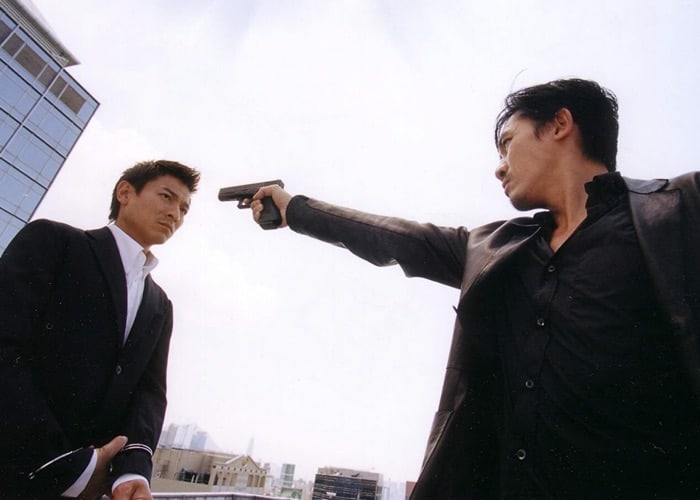

Andrew Lau and Alan Mak‘s original stars Andy Lau and Tony Leung as two warring sides of the same coin. If you’ve seen The Departed, the basic plotting is the same. Lau’s character (who is also named Lau) begins the film as a young member of Hong Kong’s mafia, the Triad. Similar to Matt Damon‘s character in Scorsese’s film, Lau is tasked by his boss, Sam (Eric Tsang), with infiltrating the police force. Lau is slippery, using his position as a mole to kybosh investigations into Sam’s gang.

Leung plays Yan, a young police cadet who shows such promise that his superintendent (Anthony Wong) asks him to immediately take on an undercover assignment in the Triad. Yan occasionally loses sight of his police roots in light of Sam’s powerful influence. The impact of his character is similar to that of his Scorsese parallel, Billy, played by Leonardo Dicaprio. But where Billy can be manic, Yan just shuts down. Leung brings a greater degree of maturity and has more bottled-up energy than DiCaprio, but it works great with Infernal Affairs‘ more ambiguous nature.

Other than the basic plotting of the films, they couldn’t be more different. Infernal Affairs has a frenetic energy and is a combination of intense melodrama and slick crosscutting. Sometimes there’s a hyper-romantic music cue and sometimes a slow-motion, quick-cut flashback sequence. Andrew Lau worked as a cinematographer for Wong Kar-Wai on two of his films, and this likely lends Infernal Affairs its ’90s arthouse influence. The filmmakers opt for tinny lighting and switch from color to black and white, especially at moments when the two main characters cross paths.

Infernal Affairs constructs its thematic foundation around the idea of fate. The focus is not on how different Lau and Yan are, but how similar. Their parallel avenues are not directly linked to an environmental factor (such as South Boston) or birth circumstances. The film leans into the sketchy moralism of each institution — mafia and police — and doesn’t land on a definite answer. A more ambiguous glint gives it a lot of intrigue. This ambiguity is also represented at the end of the film, which is one of the only major plot differences from The Departed.

In light of this impressive, flashy film about souls intertwined by fate, Scorsese’s remake surprisingly swerves away from all of it. He uses the same plot to tell a very different story in his trademark authorial style. Instead of early-aughts excess characterized by constant cuts and videogame sound effects, he uses a more classical style as a means to a thematic end. Scorsese employs his beloved voiceover at the very beginning of the film, when Jack Nicholson, playing the crime boss, says, “I don’t want to be a product of my environment, I want my environment to be a product of me.” This is a bit meta, almost as if Scorsese himself is announcing the remake as something with his artistic stamp.

Scorsese’s camera tracks, it doesn’t jerk. During one early sequence, he pans across multiple frames showing Sullivan (Damon) and Billy getting accustomed to their roles. His love of music-as-mood is made apparent in the heavy use of the Dropkick Murphys’ “Shipping Up to Boston,” a clanging metal track that riles you up just thinking about it. He uses long close-up shots to put the viewer inside the scenes and uses location shooting masterfully. When Billy and his chief are almost caught on the rooftop, Scorsese creates a lot of urgency through his camerawork that pays off with the slow-motion fall of the chief off the building and the devastating thud as he hits the ground in front of Billy.

Scorsese also switches up some of the characterizations in the film to better get to the nitty-gritty relationship turmoil he often represents in his movies. The role of the crime boss is played by Nicholson and is therefore significantly beefed up in terms of screen time and story function. His relationship with Sullivan is also much more paternalistic than the parallel in Infernal Affairs, not only because Sullivan calls him “Dad” whenever he has to make a snitch call, but it’s present in their familiarity. This makes the ending, when Sullivan kills him, more of a personal statement than the murder in Infernal Affairs, and it suits Scorsese’s interests and abilities.

One of the greatest things about The Departed is the space Scorsese gives himself to gnaw at the little slights of these interpersonal relationships, like the one between Billy and his psychiatrist Madolyn, played by Vera Farmiga. The character in Infernal Affairs is played by Kelly Chan, and her connection to Yan is more based on understanding than sexual chemistry. Infernal Affairs also gives Lau a fiancée, whose role lends an interesting sadness to the film in its final moments. Farmiga’s character is given the additional wrinkle of her connection with both men, and it creates another cobweb of relationships for Scorsese to dig into. His choice to modify the mob boss and psychiatrist characters reflects how much he loves investigating these predatory, capricious relationships.

Nicholson’s first line in the film also brings a cultural context and American-specific sociopolitical angle that is necessarily absent from Infernal Affairs. One of the threads running through The Departed is the idea of how a person’s birthplace can dictate a great deal about their circumstances, represented in each main character. Billy has a scene in the early moments of the film in which Sergeant Dignam (Mark Wahlberg) spews insults at him, attacking his parents, his upbringing, and his neighborhood. This is the linchpin to The Departed’s success as a remake. By changing the context and thematic underpinning of the film to reflect the unfortunate truth of birth circumstance, Scorsese mines new meaning from the story and creates something distinctive and impactful.

The Departed has almost an hour longer runtime than Infernal Affairs, but that fact is a credit to both films. Scorsese’s operatic approach is not indulgent, and Lau and Mak’s tight, punchy storytelling isn’t rushed. We should be asking for more out of our Hollywood remakes, and The Departed is, in many ways, a perfect example of how to do a remake right. The basic plot and even some specific story beats were grafted onto a new idea, so you get two distinct artistic endpoints. There’s so much to get out of each film, but neither one steps on the others’ toes. Infernal Affairs is spectacular, and The Departed is an absolute masterclass in a remake.

The post ‘Infernal Affairs’ and ‘The Departed’: How to Do a Remake Right appeared first on Film School Rejects.

0 comments:

Post a Comment