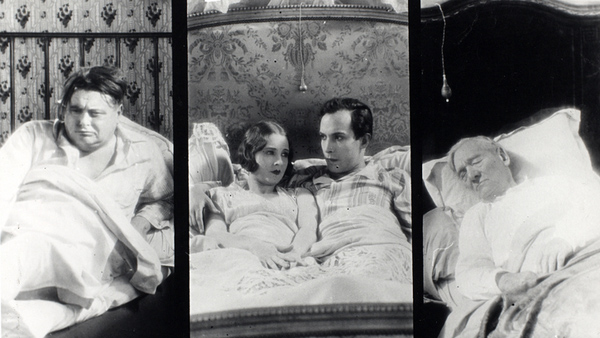

The Woman under Oath (1919).

DB here:

Hard to keep up. Herewith, some highlights as Cinema Ritrovato, the Cannes of classic cinema, winds down.

Grease, still the word

Patricia Birch has been a dancer and choreographer since she worked on West Side Story. A member of Martha Graham’s troupe, she also danced with Agnes De Mille. She designed dances for The Wild Party (1975) and both stage and film versions of A Little Night Music (1973, 1977). What brought her to Bologna was the restored version of Grease (1978). She choreographed that on both stage and screen, and she talked about it at a stimulating panel with Ehsan Khoshbakht and her son Peter Becker, of Criterion Films.

I had thought that Grease followed the vogue for boomer high-school nostalgia triggered by American Graffiti (1973), but it was actually ahead of that. The original Chicago version, reportedly raunchier than the New York version, premiered in 1971. It opened on Broadway in 1972 and ran until 1980. The film modified the stage show and added some songs.

Ms Birch was a font of information about how she conceived the numbers. She says she thinks of dance as “timed behavior,” not set steps but patterns of motion. This idea allows her to choreograph actors who may didn’t have dance training but who could “move well.” Peter ran a clip showing a passage of cascading hallway mischief that was as rhythmic as a dance number. This was one of several group-action scenes that Ms. Birch coordinated.

The Grease ensemble was huge, and Ms Birch organized it in a quasi-military way. There was a core of twenty proficient dancers, ten male-female couples. They supervised and coached the less skilled performers. For “We Go Together,” set in a carnival, each couple found business and steps for thirty other dancers.

“We Go Together” was the sort of big showstopper she called “Paramount numbers.” There were also the smaller-scaled “semi-Paramount numbers” and the intimate, character-driven “Internal numbers.” Ms Birch pointed out how the Paramounts built their power on unison steps and, eventually, massive kicklines. “People like to see the world in unison. Gets ’em every time.”

I learned a lot from Patricia Birch’s spirited discussion. Watch for a version of the panel to show up online.

Cutting edges

Film curator Olaf Müller set a new Ritrovato record: the shortest retrospective to date. Three films running less than twenty minutes introduced us to the oeuvre of Franz Schömbs.

Schömbs was a painter who became, according to Olaf, “probably the only avant-garde filmmaker of 1950s West Germany.” He started in the thirties by mounting paintings in rows, inviting viewers to walk along and sense the changes among them. After the war Schömbs tried to revive the experimentation of the Weimar period, principally through abstract films rich in color and design.

The films on the program were dense. Opuscula (1946-1952) consists of patches of color that slide to and fro “on top” of one another thanks to panning and tilting movements. The superimpositions create some striking visual hallucinations, as when blocks of white refuse to change color while other forms around them do. Die Geburt des Lichts (“The Birth of Light,” 1957, above), my favorite, transposes that constant movement to the patches of color themselves. These patches, as crisp as paper cutouts, have thrusting edges that keep slicing into the mates around them. Apparently Schömbs achieved the effect applying paint to layers of glass and adjusting them frame by frame. Den Eisamen Allen (“To All the Lonely Ones,” 1962) uses what seemed to me traveling mattes, again enlivened by rich color.

Once more, Bologna proves a showcase for films that would otherwise go missing from film history.

Trial, with error

The courtroom drama was a mainstay of early twentieth-century theatre, but in 1915, playwright Elmer Rice gave it a twist. On Trial (1915) presented a murder trial by dramatizing the witnesses’ testimony in flashbacks. Rice offered another innovation as well: his flashbacks are non-chronological, starting with the most recent incident and reserving the climax for the earliest piece of action. Using the courtroom drama to play with time and viewpoint became a staple of American theatre and cinema.

Popular culture is a teeming mass of copies and near-copies–the switcheroo principle–so it didn’t take long for other storytellers to vary and complicate the trial format. One of the neatest examples was on display in Bologna. In the John Stahl silent drama The Woman under Oath (1919), flashbacks replay key actions according to what different witnesses know. We get no fewer than six flashbacks, some presenting incidents leading up to the crime, others recounting the murder itself. The later ones fill gaps in the earlier ones and culminate in a full, accurate version of the killing.

Proving once more that 1910s cinema can be very intricate, the same pieces of action get redeployed in different witnesses’ testimony. Sometimes the camera setups are varied to differentiate the versions.

At other moments, nearly identical framings mislead us by concealing important information. The young man accused of the murder is shown near the victim in three pieces of testimony, with the first two instances being essentially identical but the last presentation providing different information. (To avoid a spoiler, I don’t show the portion of the third shot that yields that information.)

The Woman under Oath shows a sophisticated understanding of how framing can conceal information without our being aware of it. And in retrospect what seems a colossal coincidence during the first presentation of the killing turns out to be a perfectly motivated key to the solution.

Switcheroos on the trial-testimony format showed up in other Ritrovato films. By 1928, the idea of conflicting testimony enacted in “lying” flashbacks was conventional enough to be parodied in René Clair’s Les Deux timides (“Two Timid Souls”). Here the disparities are wildly comic, accentuated by split-screen and freeze frame. Albert Valentin’s La Vie de Plaisir (1944), made under the German occupation of France, is an elegant social comedy pitting a couple against one another in divorce court. The spiteful witnesses offer testimony damning the husband only to get refuted in replays that reveal extra information. Throughout world cinema, the flashback trial film seems to have been one way oblique narrative strategies were made understandable for a wide audience.

Thanks as ever to Guy Borlée for assistance, and to the Ritrovato programmers for supplying so many treats. Thanks also to Kelley Conway for discussion of the courtroom movies.

One rough precedent for Rice’s play is Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). The lingering awareness of Rice’s play is evident in Variety‘s review of The Woman under Oath, which the critic labeled “a sort of ‘On Trial’ affair” (20 June 1919, 52). In the same year there was an interesting parallel in the flashback testimony in Dreyer’s The President (1919).

You can find more about the switcheroo premise in my Reinventing Hollywood, which also discusses the trial format. For more on flashbacks see this entry. A series of entries on complex 1910s cinema start with this one.

Les Deux timides (1928).

0 comments:

Post a Comment