DB here:

The Donovan Affair was Columbia’s first all-talking picture, and Frank Capra’s as well. We discussed it a little in an entry devoted to a Cinema Ritrovato retrospective of Capra’s films. The film lacked, and still lacks, a soundtrack, which may be lost.

The Donovan Affair is an unusually fluid early talkie, and that led me to speculate we might be seeing the silent release version. Wrong! It really does survive only as a sound film without a soundtrack; the Library of Congress print I studied last month has a leader labeled “synchronized version.”

The clunky plot didn’t improve on repeated viewing, but the film did teach me some things about those transitional years 1928-1932, when filmmakers were figuring out how to make a sound feature. I thought I’d share some of those findings with you today.

But I must warn you that there’s one big spoiler coming up. I tell you whodunit. It’s necessary to make a point, but I will warn you just before the offending paragraph, so you can skip if you wish.

Blood-spattered footlights

Murder ran wild on the Anglo-American stage of the 1920s. While melodramas of love and betrayal waned, mysteries rose in popularity. There were plays about gangsters, trials, and domestic homicide. There were comedies of lethal intrigue in spooky settings, like The Bat (1920), The Last Warning (1922), and The Cat and the Canary (1922). A little more seriously, in response the rise of the genteel British detective novel (Christie, Sayers, Allingham et al.), there emerged plays that dumped murder into society drawing rooms.

You know the format. The setting is typically a mansion, with portraits, plush salons, and an impressive library. The victim, usually a bounder, deserves killing. The suspects are both high and low: businessmen, doctors, lawyers, dowagers, flappers, playboys, ne’er-do-wells, gangsters, and servants. Into this ménage steps a police inspector, often with a bumbling assistant, who will more or less skillfully reveal the culprit. In the process, though, someone else is likely to die.

The prototype is Bayard Veiller’s The Thirteenth Chair (1916), but by the 1920s Britain and the US produced a host of popular and well-reviewed drawing-room mysteries: The Nightcap (1920), In the Next Room (1923), The Creaking Chair (1924), Interference (1927), The Man at Six (1928), The Clutching Claw (1928), and The Canary Murder Case (1928). The most famous entry in this cycle is probably Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (1929), which stands out because it presents the crime from the killers’ viewpoint. The question isn’t “Who did it?” but “Will they get away with it?” Rope’s “inverted” structure (no put intended; it’s a trade term) was anticipated by A. A. Milne’s The Fourth Wall (1928).

Owen Davis’s play The Donovan Affair (1926) fits snugly into this cycle. The action starts with Inspector Killian and his assistant Carney ushering the suspects into the Rankin family library. The rakish Jack Donovan has been murdered at a birthday dinner. The circumstances are odd: To demonstrate a glowing ring Donovan wears, the lights were turned out. In the darkness, he was stabbed with a carving knife.

Most of those at the table have good reason to kill Donovan. He was having affairs with married women and had an eye on Rankin’s daughter Jean, whom David hoped to marry. The first act is centered on exposition that emerges from Killian’s questioning of the guests. One, Horace Carter, comes forward to declare he knows who the killer is, because the victim’s missing ring was slipped into his pocket. Killian doubts that the ring could have been visible, and so the lights are switched off a second time as a test. Bad idea: When the lights come back on, Horace has been stabbed with the same knife. Score one for law and order. Later one character will shoot another as Killian looks on.

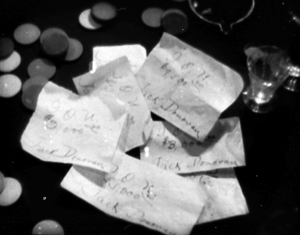

The next two acts expose more motives, lay false trails (David has brought a gun to dinner and has blood on his cuff), and string out physical clues, including a fake ring and some threatening letters to Donovan. In frustration, Killian leaves the suspects to pool their information, in hopes that they’ll discover the killer. Once more the lights are put out to allow the culprit to replace the ring and a missing letter. The killer is revealed, and there’s a struggle in semidarkness. Killian and his men burst in to seize the guilty party.

Among all this claptrap, the blackout gimmick is worked very hard. Bayard Veiller’s Thirteenth Chair had staged a stabbing in a dimly-lit séance, and Davis himself had let the electricity fail in The Haunted House (1924). The blackout-covering-a-killing would be reused in The Spider (1927). The Donovan Affair justifies the device through the luminous ring. In plot terms, it’s another red herring, but it plausibly motivates darkening the stage during the murders. The effect seems to have come off.

The audience found itself frequently strung almost to the endurance limit, and now and then a voice from the crowd would beg a relentless actor not to turn out those lights again. For it was generally in the darkness that stabbings, shootings and assorted mayhem would stalk through the play.

It must have been riveting to see the ring (a green-tinted flashlight) floating around the darkness. Capra’s film is at pains to reproduce this signature effect, but with some differences.

The screenplay subtracts some of the characters and adds a sinister caretaker and Porter, a gambler to whom Donovan owes money. The plot begins well before the crime, with an opening that establishes Porter among his cronies. A second scene shows Donovan brushing off Mary, the Rankin family maid; in the play their liaison is revealed very late. Then guests gather for the birthday dinner, and after some salon byplay they sit down to eat, with Donovan demonstrating the power of the cat’s-eye ring. In the darkness he’s murdered.

A title, “One hour later,” introduces the main stretch of the film, which corresponds more closely with the play’s action. Inspector Killian arrives and sizes up the suspects. Most of the play’s clues emerge, with suspicion scattered around freely.

Like the play, the film is built around blackouts showing off the wandering ring, but now these are motivated as reenactments of the crime. Killian puts Porter in Donovan’s seat, and in the darkness he becomes the second victim. After more intrigue, Killian demands another go-round, and this time the killer is exposed.

The film’s blackout scenes run 36 seconds, 42 seconds, and about 100 seconds for the climax. This last scene varies the treatment by showing some silhouettes.

These scenes feel surprisingly protracted: 30 seconds is a long time on the screen. Likely there would have been dialogue and sound effects, as there are in the play’s blackout intervals.

Here’s the paragraph with the spoiler. In both play and film, the butler Nelson is revealed as the murderer. (At this point in history, having hired help commit the crime wasn’t yet out of bounds.) Nelson is in love with Mary, whom Donovan has seduced. The film hints at this in a way that the play doesn’t. Mary is introduced early as Donovan’s mistress, Nelson seems to have eyes for her, and during a test to see if any woman’s handwriting matches that on a telltale letter, he lingers solicitously over Mary.

Variety praised Capra’s film as well-constructed and surprisingly funny, chiefly because of a whimsical old couple added to the ensemble. Capra claims that The Donovan Affair taught him to add doses of comedy as much as possible: “Comedy in all things.” Actually, though, Owen Davis claimed that he was teasing the genre in his original. “The Donovan Affair was, naturally, a success, although I am, I think, the only one who knows that it was as deliberate a burlesque as The Haunted House had been.”

Opening up the proscenium

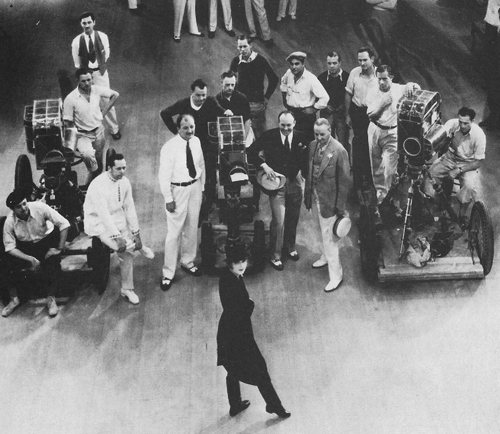

A posed shot of the multiple-camera teams for Sunny (1930).

In his autobiography Capra regarded The Donovan Affair as a turning point in his career. While complaining about the constraints on sound cameras, he regarded the film as “the beginning of a true understanding of the skills of my craft: how to make the mechanics—lighting, microphone, camera—serve and be subject to the actors.” To my way of thinking, what he did within the confines of early talkies was inject some of the pictorial fluidity and impact on display in the silent cinema. The Donovan Affair is a lot less pictorially stilted than most of the 1929 American films I’ve seen.

Like many early talkies, the film relies heavily on multiple-camera shooting of the sort still used in TV comedies and soap operas. For this film, according to Joseph McBride, five cameras were used. The range of coverage allowed for continuous sound recording while preserving the option of analytical editing. While one camera recorded a wide framing, a long lens could scoop out a closer view without moving that camera into the space.

So when Mary calls on Donovan in the second scene, we can see her arrive in a long-lens mid-shot, then we can see Donovan’s reaction in a long shot. Mary comes forward and a third camera picks them up in a two-shot.

The technique permits smooth matches on action, as when Mary turns her head in a medium shot and leaves in the background of the master shot.

But it’s also clear that multiple-camera shooting allowed for alternative takes. The mismatches we can detect across some cuts suggest this. /During continuous dialogue, Lydia’s arm is up in one shot and down in the next.

Capra claims that Columbia allowed him to print only one take, but he got around this by not slating his shots. He simply let the camera run and replayed the action, sometimes several times. This allowed actors to improve their performances in a fluid process. He wound up with only one take number, out of which he could pick the take he wanted. This might explain disparities of figure position like this.

Multiple-camera shooting could yield some awkwardness, especially when shot scale wasn’t adjusted. Here’s an interesting example showing Jean’s quarrel with her stepmother Lydia. As Jean crosses in front of Lydia, the match cut on my second frame below creates a little bump by not sufficiently changing the angle and figure size. The slight pan following the women accentuates the disparity.

A jerky cut like this would be very rare later in the 1930s, as it is today. As recording technology improved, Hollywood would move back to single-camera shooting for most scenes, and shot scales were more exactly planned and executed.

If multiple-camera shooting feels a bit theatrical, it’s because it surrenders a degree of freedom in camera placement. We always seem to be watching things from outside a proscenium, even when items are enlarged. I think that the early talkies’ habit of starting with a flamboyant camera movement, as in Sunny Side Up (1929) and The Broadway Melody (1929), was a way of saying, “Don’t worry, this is still cinema.” Capra follows this habit by beginning on a close view of a pile of Donovan’s IOUs and then tracking back very far to set his first scene among the gamblers.

The film’s second “act” starts with a comparable flourish. A long shot of the library shows Carney bustling toward the offscreen front door in the background. The camera tracks in and waits for him to return.

Presumably we would be hearing him greeting Inspector Killian offscreen, but the frame is empty for about fifteen seconds. Then Carney and Killian stride in, and the camera pulls back to something like the initial master framing.

Another way to add fluidity was to insert shots that don’t require lip synchronization. Cutaways to objects or reaction shots could be inserted into the dialogue-laden stretches. For example, Nelson and Mary peer into the library to watch the guests, and Ted Tetzlaff’s cameras give us two shots from positions different than we’ve seen so far.

More boldly, after Donovan is killed, Capra gives us not only a shot of Mrs. Lindsey wailing but brief close-ups of Jean’s and Lydia’s reactions.

These two shots are only 32 and 36 frames respectively, harking back to the punchy montage of silent cinema, and they stand out by contrast with the extreme long-shots around them.

Similarly, you have to think of all those subjective POV shots in 1920s silent films when we watch Killian survey the suspects. As he talks with Rankin, he scans them right to left in a series of POV shots, including one longish, zigzag pan. Here are some extracts.

The end of the pan shot shows Lydia shifting her gaze from Killian to her husband, off left. We then cut to her husband and Killian, who’s just finishing his scanning of the suspects. Her gesture cast suspicion on her; after all, she’s hiding her affair with the dead man.

Most ambitious of all is Capra’s handling of the dinner table situation. Smoothly integrating singles and two shots of characters around a table was one of the triumphs of classical Hollywood style in the late 1910s. Matching character positions and eyelines from shot to shot became part of every director’s craft. Capra adapts talking pictures to these constraints in a flow of shots that include dialogue and keep all characters’ relationships clear and consistent while picking out important details and reactions.

For example, when Donovan talks with Mrs. Lindsey, we get her husband’s glare as he watches from across the table.

Here the proscenium is broken. Instead of covering the action from outside, now the camera penetrates space and can take up a variety of angles among the characters.

This camera ubiquity can be exploited to dramatize the murder weapon. A master shot shows the dinner party, with Rankin at the head of the table and his wife Lydia at the foot, turned from us.

Mary brings the roast and the carving knife to the table. Cut in to Mary lifting the knife, which glints.

Donovan flinches as the reflection dazzles him. Cut to Lydia, from the foot of the table, saying, “Mary,” and looks down the table to where Mary would be.

We’re in a sort of triangular space—Mary-Donovan-Lydia—and the relationships are reaffirmed when a return to the earlier setup shows Mary responding to Lydia’s look.

The dialogue continues within these shots. Capra’s changing setups must have required quite a bit of effort in 1929, what with cameras in booths and the pressures to stick with continuous multi-camera takes. But, reviving silent-film table coverage, he gives us what would be one conventional way to handle such an action in the 1930s.

There are other felicities in the film, but I think I’ve said enough to indicate how it’s an enlightening transitional work. Tied to the multi-camera technique for most of its running time, Capra breaks away for significant stretches. He found a way to give camerawork and cutting some moments of the sort of fluidity that would pervade Hollywood in the 1930s.

Capra wasn’t the only major director to cut his talkie teeth on adaptations of stage thrillers. Hawks made The Criminal Code (1931) from a 1929 prison drama, while Hitchcock based Blackmail (1929) and Number Seventeen (1932) on popular plays from 1928 and 1925. Film mysteries would change in the 1930s, with sophisticated detective comedies like The Thin Man and adaptations of the adventures of Charlie Chan and Perry Mason.

Creaky though it might seem in later decades, the manor-house murder would remain a reference point. On stage its premises were given a new twist in Christie’s The Mousetrap (1952), enhanced with social criticism in J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls (1945), and parodied in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1962). You can argue that the provincial procedurals with a British accent (Wexford, Midsomer Murders, Inspector Morse, and so on) grow out of the spillikins-in-the-parlor tradition, but shifting the viewpoint to that of the detectives.

Thanks to Lynanne Schweighofer, Zoran Sinobad, and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress and Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach of our Cinematheque for arranging my viewing of The Donovan Affair. Thanks also to Ben Brewster for discussions of the film and 1920s theatrical practice.

A fleshed-out synopsis of the film was published at the time.

Bruce Goldstein had the excellent idea of adding live performers to screenings of The Donovan Affair. He details his efforts to find the original dialogue in this TCM article.

My quotation about rapt audiences for the stage version comes from the review, “’The Donovan Affair’ Thrills in Mystery,” The New York Times (31 August 1926), 15. Quotations from Capra are from the first edition of his autobiography, The Name above the Title (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 105. Joseph McBride has written the most comprehensive and probing biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

In his autobiography Owen Davis remarks that the failure of The Haunted House, a “burlesque mystery melodrama” impelled him to write The Donovan Affair. That was a play that “could hardly be accused of not being mysterious enough, and one that actually dripped with blood and missed no trick at all of the tried and true tricks of mystery story writing from Gaboriau through Poe and Doyle and Anna Katherine Green and Mrs. Rinehart, even taking in the tricks of the present, and very skillful, crop of hard-boiled detective story writers who were at that time printing their first compositions on a slate in some primary school.” See My First Fifty Years in the Theatre (Boston: Baker, 1950), 94-95.

My exploration of theatrical thrillers has been aided by Amnon Kabatchnik’s two excellent reference books: Blood on the Stage: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire, 1900-1925 (Scarecrow, 2008) and Blood on the Stage, 1925-1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire (Scarecrow, 2010).

As ever in such matters, Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website offers background information and critical discussion of authors, periods, and conventions.

On multiple-camera shooting in early sound film, see Chapter 23 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. A good primary source is Karl Struss’s article “Photographing with Multiple Cameras,” TSMPE XIII, 38 (1929), 477-478.

The Donovan Affair (1929).

0 comments:

Post a Comment