Beyond the Classics is a bi-weekly column in which Emily Kubincanek highlights lesser-known old movies and examines what makes them memorable. In this installment, she investigates the origins of film noir with John Garfield in Busby Berkeley’s They Made Me a Criminal.

Film noir has never been an easy genre to pin down. A film’s dark and gloomy cinematography can earn noir status. The crime-ridden plot can qualify as noir. A double-crossing femme fatale can turn a mystery into a noir. It may be hard to define noir in a way that captures all its possibilities, but you know when you see it. This is especially true when looking back at movies that came before the film noir genre took hold. Crime dramas, gangster films, and other 1930s films contain elements of the noir movies of the following decade. And looking back at movies like 1939’s They Made Me a Criminal helps reveal how Hollywood inched towards a more cynical representation of America and how it persecuted its own in the process.

The last director we’d usually associate with film noir archetypes is the famed choreographer Busby Berkeley, who is known for his involvement in elaborate Depression-era musicals like Footlight Parade and The Gold Diggers of 1935. At the end of the 1930s, his musicals were on the decline at the box office, and he longed to move towards more serious films. Warner Bros. handed him They Made Me a Criminal, a remake of 1933’s The Life of Jimmy Dolan. Berkeley’s version was the perfect vehicle for the studio’s newcomer John Garfield, a young and rebellious actor fresh out of Lee Strasberg’s troupe at the Group Theatre and fresh off an Academy Award nomination for his first Hollywood role.

Garfield plays champion boxer Johnnie Bradfield, who has fooled the public into believing he’s a real stand up guy. But that all changes the night after his big win. While celebrating with his manager, Doc (Robert Glecker), his girl, Goldie (Ann Sheridan), and her friends, Johnnie gets into a drunken brawl but blacks out before he can witness Doc murder a man. Doc and Goldie take Johnnie with them when they flee the scene, but they abandon his unconscious body when they realize they won’t be able to prove their innocence.

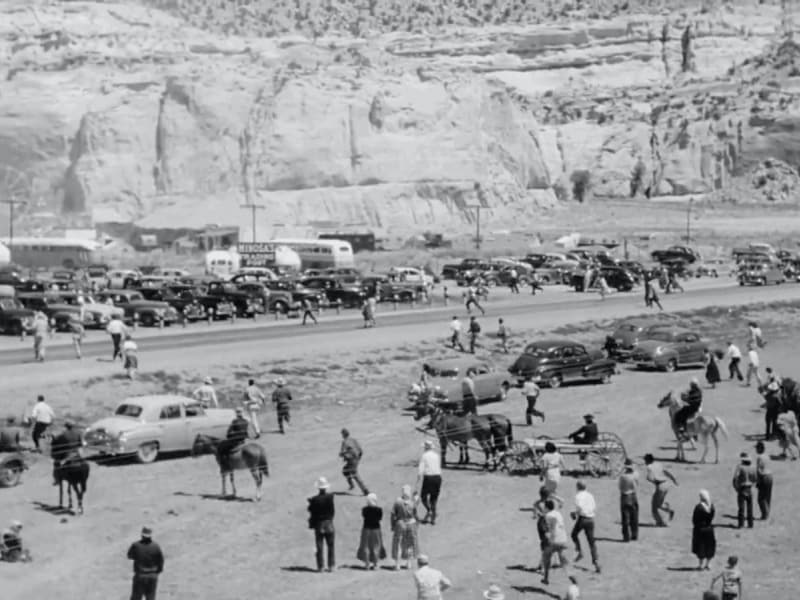

As they leave Johnnie to fend for himself, the two double-crossers are chased by police and perish in a violent car crash. Police assume the man in the car is Johnnie, and the real boxer wakes to find the world thinks he’s not only a murderer but a dead one, too. He must flee from New York and assume a new identity to evade the one detective (Claude Rains) unconvinced of Johnnie’s death. Johnnie ends up in the care of two women who reform delinquents on their Arizona date farm. As he tries to make a new life, Johnnie can’t shake his champion boxing ways and risks his freedom for some prize money.

They Made Me a Criminal lacks the high-contrast cinematography associated with film noir. Berkeley is unable to completely shed the light-hearted comedy and corny romance of his previous films. These aspects keep They Made Me a Criminal from being a strictly serious crime drama. However, it holds a lot of elements the genre would adopt in the following decade. Garfield’s Johnnie has the cynical look on life synonymous with noir criminals and hard-boiled detectives. He’s got questionable morals to match. Everyone in life is a “sucker” if they’re not taking advantage of someone else, and because of that, he trusts no one.

Johnnie’s drunken monologue about the unfairness of the world sounds like it was plucked out of Double Indemnity or Out of the Past’s voiceover narration. This “nobody’s got any friends” attitude proves to be right, at least in terms of those closest to Johnnie. His manager and girlfriend leave him in the dust, despite being his closest allies earlier in the night. Johnnie’s hard look on life follows him into his new life in Arizona, even when farm owners Peggy (Gloria Dickson) and Grandma (May Robson) prove they’re nothing but good-hearted.

Even though she’s only in the film for about fifteen minutes, Ann Sheridan makes an impact as Goldie. She’s got everything the iconic femmes fatale embody in noir movies that follow. Goldie knows how to seduce a man. She has Johnnie wrapped around her finger, even though he knows she’s only with him for the money, the fame, and presumably the sex. In the span of one night, Goldie goes from Johnnie’s fun girlfriend to ruthless double-crosser. She doesn’t take much convincing to leave Johnnie for dead and seems to be thrilled to go on the run with Doc. After all, he’s the one in control now, and a femme fatale always sticks by the man who’ll benefit her the most.

Sheridan’s transition from sexy girlfriend to back-stabbing femme fatale is comparable to Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai or Joan Bennett in Scarlett Street. Sheridan’s Goldie embodies exactly what Halley Sutton describes when talking about the femmes fatale in classic film noir: “You know her the moment she’s on-screen: she’s got the best lines and the best wardrobe. She’s having more fun than anyone else around her—which usually means she’ll have to be punished by [the] film’s end.” That punishment comes swiftly for Goldie, but her brief time in They Made Me a Criminal provides the framework for the dangerous female characters that follow her film history.

Johnnie’s predicament is one that mimics later crimes in famous films noir. He wakes up having a murder pinned on him and has to prove his innocence or run away from the possibility of being caught. It’s extremely film noir for a character to be mistakenly considered dead. In fact, this happens in several noirs like Laura and The Third Man. Even more common in noir is the idea that an innocent man is framed for a crime he didn’t commit: The Wrong Man, The 39 Steps, Kansas City Confidential, and Nightfall are just a few that have characters faced with the same problem Johnnie deals with in They Made Me a Criminal.

This precursor to film noir does more than just foreshadow the newfound genre that would take Hollywood by storm. It also represents the persecution of its star. Garfield is just feeling out his persona as the antihero and cynical criminal in They Made Me a Criminal. The movie forces a happy ending on Johnnie, making sure he’s redeemed and proven to be a good man after all. Garfield’s roles after Johnnie would continue to get darker and more desperate, leading him to the film noir role we best remember him by today: Frank Chambers in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Garfield had a promising career as the brooding, working-class manly men of film noir and prestigious dramas, but Hollywood’s conservatives and the FBI cut his career short.

Garfield became the biggest star to fall victim to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigations into supposed Communists of Hollywood — what is known today as The Hollywood Blacklist. In the late 1940s and 1950s, the United States was thwarted into a Communist scare, suspecting any citizen who exhibited left-wing ideals to be a Communist and a major threat to the American way of life. Hollywood became the government’s most dramatic target, and they put suspicious filmmakers, writers, and actors on trial for the world to see.

Born Jacob Garfinkle, Garfield was guilty by association in HUAC and Hollywood’s eyes. He was the child of working-class Jewish immigrants from Russia, a combination sure to signal a Red allegiance. During his days at the Group Theatre, he worked with actors and playwrights who held radical ideas and snuck them into the social problem plays they put on stage. Garfield’s wife Roberta was a former Communist, but there was no evidence that Garfield himself was a member of the Party. He was never shy about his liberal political views and advocated fiercely during and after World War II against fascism. His on-screen persona, a working-class man who distrusts inherently American ideals, was an even better reason to suspect Garfield was corrupting Hollywood films with a Communist agenda.

In 1951, Garfield got the dreaded subpoena from HUAC to appear in court and prove his innocence. He denied that he ever was a Communist or knew any Communists within Hollywood. Just as the other HUAC victims who refused to name names of suspected Communists, Garfield became the kind of actor to avoid in order to evade investigation. He was never cast in another Hollywood film after his testimony, even though the FBI had nothing to prove he was a Communist. Making a movie with the man who was the go-to rebel was just too dangerous. Even if he was innocent, the government had already made him into a criminal.

Following his HUAC prosecution, Garfield was constantly surveilled by the FBI and put under immense stress as his career was at a halt. He became desperate, moving back to New York and entering the theater scene again. His last-ditch effort to win the public’s trust back was an essay he planned to publish in Look magazine. He would confess how he was duped by leftist ideals and denounce communism once and for all. The title of this essay, “I was a Sucker for the Left-Hook,” was a direct reference to They Made Me a Criminal, in which Garfield’s Johnnie is known for his left-hook in the boxing ring and his affinity for the term “sucker.”

The essay would never see the light of day, however. After an agonizing year for Garfield, he died of a heart attack the day after his name was mentioned in front of HUAC once again in 1952. This time, Clifford Odets vouched for Garfield’s innocence. It was too late, and many believe the stress of his blacklist led to Garfield’s tragic death at 39.

Garfield should have had the long career of fellow stars like Robert Mitchum, Humphrey Bogart, and James Cagney. They were able to act into their old age, solidifying long-lasting reputations as some of the greatest actors in Hollywood history. In They Made Me a Criminal, Garfield’s Johnnie gets a happy ending when the detective ready to take him back to New York in handcuffs changes his mind. He recalls how he persecuted an innocent man and sent him to the electric chair in the past, a mistake that haunts him to this day. He refuses to make that same mistake again and lets Johnnie live out the rest of his days in Arizona as an innocent man.

If only Busby Berkeley could have given that happy ending to John Garfield himself. Revisiting this early performance helps us remember that Garfield didn’t just make film noir films great, he helped bring the genre into being.