The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley continues its editions of classic silent films previously unavailable on disc or available only in inferior copies. Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features, Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927), and The Heir of Genghis Khan (commonly known in English as Storm over Asia, 1928), are packaged here as “The Bolshevik Trilogy.” (As of now, the discounted price at Flicker Alley’s own site is considerably cheaper than what Amazon is charging.) All three films have appeared in my annual survey of the ten best films of ninety years ago; see the entries for 1926, 1927, and 1928.

The only restoration in the set is Storm over Asia, done in connection with Lobster Film in Paris.

Mother

Pudovkin’s trilogy is a sort of survey of key events in Russia’s move toward becoming the Soviet Union. Mother, based on Maxim Gorki’s novel of the same name, deals with the failed Revolution of 1905. That revolt was viewed as an important precursor to the Communist Revolution of 1917. Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) was an anniversary film for the same struggle.

Pudovkin is known for centering his films around individual protagonists rather than the group protagonists favored by Eisenstein in his first three silent features. Here the hero is Pavel, a young worker and clandestine revolutionary who lives with his drunken father and downtrodden mother. When guns that Pavel has hidden in the house are discovered, the mother naively betrays her son to the police. He is imprisoned. After a prison break, Pavel joins a protest march, and his mother, now converted to the rebellion, sees him mowed down but carries the flag onward.

Pudovkin’s style is already fully formed here. It’s very flashy, employing the usual fast cutting and depending on highly unconventional ways of framing shots. Pavel’s escape from prison, for example, contains a bird’s eye view as he climbs down some railings to help his comrade put a guard out of commission (above) and a shot during Pavel’s trial uses one of the director’s favorite compositions, shots of police or soldiers seen past their horses heads.

Pudovkin also tends to use imagery of nature to symbolize the revolutionary impulse, as in the famous breaking up of ice on a river during the prison break and protest march. Rivers and lonely trees against low horizons appear in all three films, and the escape over ice floes returns in Storm over Asia (see bottom image). Such techniques perhaps help explain why Pudovkin was the most popular of the major Montage directors.

Given the importance of having these three films available, I hate to find fault. This print of Mother is simply the old Blackhawk/Image. It’s certainly acceptable, but a restoration of Mother, and as we shall see below, The End of St. Petersburg remains to be done. That better prints exist is shown by the illustrations I used in the 1926 entry linked above, which were taken from a 35mm archival copy.

The End of St. Petersburg

For many film fans, The End of St. Petersburg is perhaps the least emotionally involving of these three films. Pavel in Mother and the unnamed Mongolian hunter in Storm over Asia are appealing characters, friendly, brave, and ready to stand up to imperialists, soldiers, and police–and both the victims of flagrant injustices. The unnamed peasant who is at the center of The End of St. Petersburg is initially an ignorant, selfish young man. In a time of famine shortly before World War I, he goes to the city in search of work and becomes a scab, working at a large factory during a strike.

The peasant is friends with one of the workers who fomented the strike, and, echoing the actions of the mother in the earlier film, naively betrays the man to the management of the factory. Once the war breaks out, the peasant stolidly suffers through the entire conflict at the front. Only late in the film does he realize his folly and join the Bolsheviks in the 1917 attack on the Winter Palace. This ends the period when the city was named St. Petersburg.

The peasant is also not in the film nearly as much as the central characters of the two other films. Instead of a compact dramatic narrative, Pudovkin takes us from an era in which the stock market rules society through the war–also waged for the benefit of capitalists–to the Winter Palace attack of October, 1917. The peasant weaves through this, but there is no real point-of-view figure.

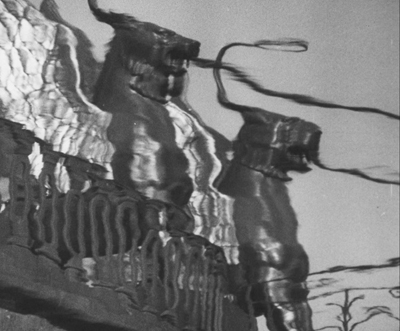

The End of St. Petersburg is a marvelous film nonetheless. In his survey of revolutionary progress, Pudovkin’s flashy style is even more self-assured. In a sense, the city becomes the central symbolic source, with the statues for which St. Petersburg (as it is now again known) is famous representing the power against which the Bolsheviks revolt. The opening scene includes a remarkable series of shots, not of the famous landmarks, but of their reflections in the city’s canals, filmed and then shown upside down, as if the city is shimmering with the weakness that will soon bring down its rulers. The image above shows the griffins holding the cables for the well-known suspension pedestrian bridge, the Bank Bridge.

There are fascinating parallels to Eisenstein’s October, which came out a year later. Both films were among three made to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Revolution. The End of St. Petersburg and Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October were finished and released in the anniversary year, but Eisenstein’s was not. Pudovkin and Eisenstein shared a fascination for the rich Tsarist trappings of the Winter Palace, which were, according to them, enjoyed by the short-lived Provisional Government and its supporters. Certainly The End of St. Petersburg contains some beautifully composed and lit shots of decadent luxuries surprisingly similar to those Eisenstein filmed. (See top.)

The print shares the cropping problems that I pointed out in my 1927 post including The End of St. Petersburg. Since this version is, like earlier releases, based on a 1960s Gosfilmofond “restoration” that sliced off the left of the frame to make room for a recorded soundtrack, all of the shots are too square. I was frequently aware that the frame was simply too close, eliminating part of the image. (The lady in the image at the top was originally more centered in the composition.)

As if to compensate for this problem, the visual quality of this print is startlingly good, as the images immediately above and at the top show. The clarity of the images is actually better than that of the restoration of Storm over Asia. I cannot resist showing another example. Here, in the final attack on the Winter Palace, there is an amazing precision of the lighting in picking out each member of the group of soldiers waiting for the signal to launch the offensive.

We still need a restoration of this film with the full width of the original. In the meantime, however, this version is a substantial improvement over earlier video releases.

Storm over Asia

Pudovkin completed his survey of the creation of the revolutionary struggle with an unusual choice: to set his story in one of the countries that would become close allies of the USSR. It takes place in the early 1920s in Mongolia, where White Russian forces were battling the Chinese for domination. The Bolsheviks formed an army in Mongolia and ultimately helped the country win its freedom. (Pudovkin distorts history by making the imperialist government British.)

The Mongolian hunter is played by Valerii Inkhizinov, a Mongolian citizen who had studied under Lev Kuleshov alongside Pudovkin. His character is cheated by British agents who cheat him out of the fair price for a rare, valuable fox fur (above). His retaliatory attack makes him a fugitive, and he joins a partisan group of Bolsheviks in the mountains simply in order to survive. He is eventually arrested and shot, but a document he carries seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. Nursing him back to health, the British officials exploit this connection to their own advantage. Ultimately he rebels. A final fantasy sequence has him leading at attack by partisans as a huge tempest symbolically sweeps away the British army

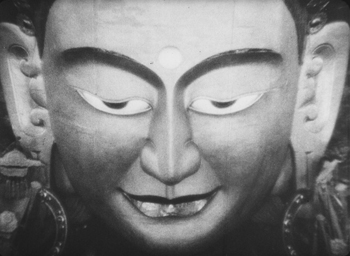

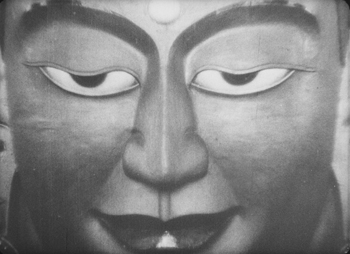

There are virtuoso passages of editing. One comes when he rebels against being cheated over the price of his rare fox fur. Another comes at the end, during the symbolic tempest. In between, Pudovkin often follows a convention of Montage filmmaking, breaking scenes into multiple shots. When a British official and his wife visit a local temple, Pudovkin strings together five increasingly close views of the face of a large statue.

Although the three films have no overlapping characters or social situations, they play very well as a trilogy.

This Blu-ray pair of discs is not a perfect restoration of the three films, but it is so much better than what was available before that this becomes a vital addition to any collection that purports to covers the basic historical classics of the silent cinema.

The set includes several informative extras, including a booklet essay by Amy Sargeant, author of two books on Pudovkin, and two commentaries by present and past curators at George Eastman House: Peter Bagrov on Mother and Jan-Christopher Horak on Storm over Asia. Some short videos analyzing Pudovkin’s editing and showing 1920s footage of St. Petersburg are also included.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley authored an in-depth book-length study, The End of St. Petersburg (I. B. Tauris, 2003).

Storm over Asia (1928)

0 comments:

Post a Comment