Kristin here:

Last May, I posted an entry responding to all the lamentations about a supposed slump in box-office revenues for theatrical films in the early months of 2019 compared with the same period of 2018. I pointed out that the cause of the slump was not due, or at least not entirely due, to a sudden lack of interest in movie-going resulting from the rise of streaming. The main reason was that most of the biggest BO hits of 2018 had been released earlier in the year than usual. As a result, most or all of their income came entirely within the calendar year. In tallying annual BO, however, money brought in after December 31 gets added onto the new year’s tally.

Thus the fact that the four biggest hits 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom, all came out in the summer or earlier. No revenues from these films carried over into 2019. That almost inevitably meant that there would be a decline in 2019, but it wasn’t due to people deciding to camp out on their couches and watch stuff streamed to their TV sets. They had simply bought their tickets to those movies long before.

For some reason, pundits never seem to notice this. Or maybe some do, but, as I wrote last May, it’s much more dramatic to tear one’s hair over a dire slump than to point out that these ups and downs really don’t reflect any dramatic changes in the overall industry, at least not yet. Also, it’s more difficult to figure out and then explain the results of the fact that films still in release at year’s end have their grosses divided between two calendar years.

Assuredly there has been big shifts in the balance of power among the major studios. Obviously Disney is doing very well indeed, with seven films in the top ten domestic grossers for 2019, including all the top six. In contrast, Paramount, long ago the most powerful studio in the young Hollywood, is in a sad state. Quite possibly it will disappear into a larger firm, as 20th Century-Fox did. This imbalance within the current industry is not good for any of them apart from Disney, but it has so far had no discernible effect on the industry’s earning power as a whole.

Annual box-office totals, in numbers not adjusted for inflation, are percolating along as usual. There was no slump last year, just a little adjustment downward after a record year. Let’s take a look at what’s really going on.

Up and up, and down, and up and up

We’re barely into 2020 and already the trade papers are pointing out that the domestic box-office total for American theatrical films fell in 2019. Yes, but …

Here’s a chart from Box Office Mojo of the grosses since 2009, the first year when the figure topped $10 billion. (These figures are in dollars unadjusted for inflation. The three columns on the right side are number of features released, average take per film, and the top grosser of the year.)

Note for a start that there was a 7.4% rise in 2018 over 2017. In 2019 there was a drop of 4.8%. Now note that the decline of 4.8% in 2019 still left the total higher than it had been in 2017. Note also that this has usually been the case. The years of big growth–10% in 2009, 6.5% in 2012, 7.4% in 2015 and 2018–are followed either by smaller rises or by declines that do not wipe out the gains of the previous years.

If you look at the larger chart from which this was excerpted, it’s much clearer that theatrical income has risen impressively.

BO has nearly quadrupled from 1985 (again, in unadjusted dollars, so a significant part of that growth is inflation). In 1985 the total was a mere $3,041,480,248. Since then there have been 27 up years (though a few were nearly flat) and only 7 down years. Down years tend, not surprisingly, to come after record years. In 2014, there was a decline somewhat greater than that of 2019. Between 2014 and 2019, the total BO rose by 14.4%. About half of that, 7.4%, was in 2018, almost inevitably leading to a decline in 2019. But really, is a 4.8% decline that big a deal in comparison with a 14.4% rise? The basic point is that the BO continues to climb overall, despite these occasional “adjustments,” as business people would call them.

Moreover, note that 87 more features were released in 2018 than in 2019, and considerably more films than in previous years. Given the average box-office gross in 2018, that would add a little over a billion dollars. In fact the difference between the 2018 and 2019 totals was only about $570 million, so presumably some of those extra films brought in well under the average. Still, some of the record year was due simply to a greater number of films. Conversely a drop in the number of 2019 films to something closer to normal does not suggest a slump due to waning interest in theatrical movie-going.

Writing in Hollywood Reporter in November, 2019, Pamela McClintock made the 4.8% drop sound like a big deal, even while acknowledging that in fact 2019 would be the second biggest BO year in history (in unadjusted dollars, of course). McClintock’s figures differ slightly from the chart above, partly because final tallies were not in and partly because she used Comscore figures instead of Box Office Mojo ones.

With Dec. 31 fast approaching, industry leader Comscore projected Sunday that box office revenue in North America will hit $11.45 billion for the full year, a decline of 3.6 percent from 2018’s record bounty of $11.88 billion.

If Comscore’s rough estimate is correct, that would be the biggest year-over-year decline since 2014, when domestic revenue tumbled a steep 5.1 percent over 2013 to $10.36 billion. The North American box office rebounded in a major way in 2015, rising 7.5 percent to $11.13 billion.

The good news: $11.45 billion would represent the second-best showing of all time, besting the $11.38 billion collected in 2016 (a 2.2 percent uptick). Underscoring the cyclical nature of the film business, revenue was down 2.3 percent in 2017, followed by last year’s dramatic 6.9 percent jump.

While international box office numbers aren’t yet tallied for 2019, analysts expect worldwide ticket sales to match, or best, last year’s all-time high of $41.1 billion.

“Given the level of competition from a plethora of options across multiple platforms on an incalculable number of devices, it should be actually heartening to the industry that 2019 will deliver the second-best annual box office revenue in history,” says Paul Dergarabedian of Comscore.

Yes, it should, but again, second-best is not as dramatic as a worrisome slump. After all, the threat of streaming to theatrical business is the big story of recent show-biz journalism.

Carry-over into 2020

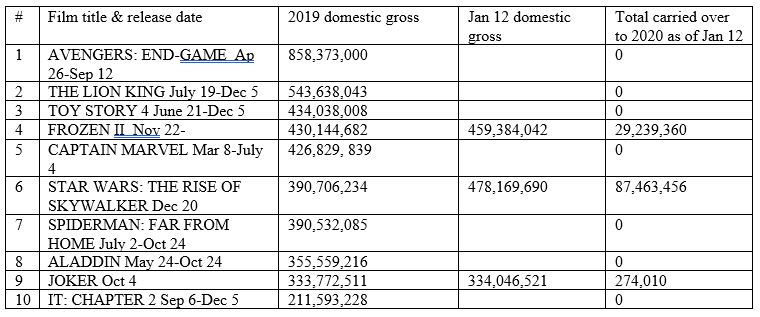

Is there likely to be much carry-over of box-office revenues from 2019 films into 2020? In other words, is there likely to be a repeat of 2019, with too many big grossers released well before the end of the year? It does seem possible. My home-made chart above, derived from Box Office Mojo figures as of January 12, 2020, shows that seven of the top ten domestic-earners went into and out of release in the spring or summer, somewhat as the comparable films from 2018 did. Of the three films still in release, Frozen II and especially Joker seem to have already earned much of what they will earn. (Indeed, Frozen II has already slightly outpaced my prediction, based on the gross of the original Frozen in adjusted 2019 dollars, $441.8 million.) The Star Wars entry, the latest release in the top ten, is still going strong and should contribute a fair amount.

1917 will provide most of its income to the 2020 figures. It opened in only eleven theaters on Christmas Day, stayed at that level for two weeks, and went wide (into 3434 theaters) on January 10, meaning that all but $2,721,279 of its domestic income will count for 2020. The film’s surprise Golden Globes wins and possible BAFTA and Oscar awards may help land it a higher gross than many would have predicted. As of January 15 it had grossed $51,561,309 domestically and was still at number one.

It’s way too early to predict what effect all the as-yet unearned carryover money from 2019 films will have on the 2020 total we’ll be discussing a year from now. I haven’t yet bothered to survey the new year’s anticipated blockbusters and their release dates. If studios continue to scatter their big earners throughout the year instead of saving them for the November-December holiday season, then carry-over income will be less significant and will perhaps cause fewer ups and downs. If so, pundits will need to find something else to make us nervous as regards the future of movie-going.

That something should not be the extremely common claim by journalists that streaming is killing theaters. It has been shown that people who stream more movies also go to more movies in theaters.

A final point

While noting in passing that 2019 both suffered a big decline and was the second-biggest BO year, Rebecca Rubin of Variety pointed out that the global box-office haul for 2019 hit $31.1 billion, the first time it has ever topped $30 billion. This rise in part reflects the fact that nearly 70% of Avengers: Endgame‘s total grosses came outside the US/Canadian market.

Rises in foreign ticket sales don’t entirely compensate for declines in domestic ones. Not as great a percentage of the box-office income returns to the American studios from some markets–notably China, which pays back 25%, as opposed to closer to 50% from other markets. (Ryan Faughnder and Robin Dixon summarized that and other problems faced by American films in the Chinese market for the Los Angeles Times last February.) But any foreign income helps, and so far the foreign markets continue to rise, even as streaming penetrates more of them.

0 comments:

Post a Comment