Making Montgomery Clift (2018).

DB here:

Our days and nights at our annual film festival would have been hopelessly frustrating if we hadn’t already seen several of the fine items on offer. At other festivals we caught Asako I and II, Ash Is Purest White, Dogman, The Eyes of Orson Welles, The Girl in the Window, Girls Always Happy, The Image Book, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lucky to Be a Woman, The Other Side of the Wind, Peterloo, Rosita, Shadow, Styx, Transit, and Woman at War. As you can see, our programmers assembled a spectacular array of movies. Most of these we’d happily watch again, but there were so many new offerings we had to resist.

With this elbow room I could pay attention to three documentaries I’d been looking forward to. They had all the appeal of a fictional film, with keen plots and tricky narration and fascinating characters. It didn’t hurt that two were about world-class celebrities and the third appealed to my deepest conspiracy-theory instincts.

Heart of Glasnost

Werner Herzog’s Meeting Gorbachev was a surprisingly conventional effort for this legendarily odd filmmaker. As my colleague Vance Kepley remarked, Herzog typically makes documentaries of two types. He probes eccentric personalities (the “ski-flyer” Steiner, or a man trying to hang out with grizzly bears) or he treks into remote, dangerous landscapes (Antarctica, a swift-moving volcano, the fires of Kuwait).

But this portrait of Mikhail Gorbachev is neither. Herzog’s interview with the elderly but still vigorous Soviet leader is interrupted by biographical inserts tracing his career, his struggles, and his policies. Newsreel footage and other talking heads provide context in a mostly straightforward account of the man’s life and work. Only a story about tree slugs briefly diverts Herzog’s attention.

The film revives our appreciation of a politician many people have tried to bury. Gorbachev emerges as a thoughtful, upbeat man who tried to make the Soviet Union more democratic and open to the popular will, to create Communism with a human face. But he triggered events that cascaded too quickly. He broke up the USSR but also cleared a path for economic collapse and a corrupt kleptocracy. His suggestion for his tombstone inscription: We tried.

Herzog’s montages dramatize the breakdown of national borders, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the coup that destabilized reforms while Gorbachev was away from Moscow. The main principle of swimming with sharks in a bureaucracy is: Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do until you do it. The 1991 unseating of Gorbachev by Yeltsin reminds me of a second: Don’t take vacations.

Meeting Gorbachev is actually a double portrait, because Herzog puts a good many personal feelings into it. He remembers the emotion he felt as Germany reunited. Gorbachev’s call for “a common European home” rouses him to recall his youthful Wanderjahr when he walked across the continent.

Although I don’t think the name Trump is mentioned, his shadow falls over the whole film. Portraying a sane, reasonable leader today seems virtually a bid for controversy. Gorbachev reminds us of the reductions in nuclear weaponry that he negotiated with Reagan and Thatcher. “People say that Reagan won the Cold War. Actually, it was a joint victory. We all won.” The idea of pursuing policies that benefit the whole world seems oddly old-fashioned right now.

When Herzog gives us a glimpse of a robotic Putin peering down into the casket of Gorbachev’s beloved wife, we’re forced to register what Russia has become, and how the US is now complicit with it. Maybe this film has more of the director in it than I initially thought. As Herzog dared to declare in an earlier film, Nosferatu lives.

Unmaking an icon

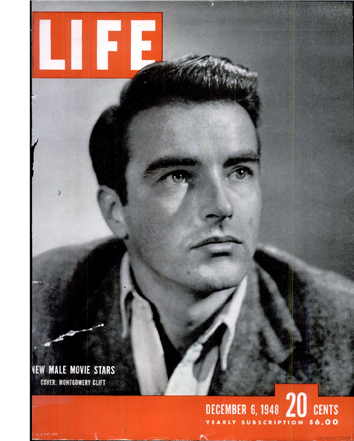

Whenever I see Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift kiss in A Place in the Sun, I think: Here are the two most beautiful people in the Western world. I’m not alone. Clift was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars after the war, partly because he didn’t easily fit the molds of either the old guard or the new.

In this context, Clift looks like cannon fodder. Put him alongside Lancaster in From Here to Eternity, and you’ll find it hard to believe he’s the prizefighter; in that movie, only Sinatra looks skinnier. Delicate, with an innocent stare and an angular body, a wide-eyed Clift takes over his debut film, Red River (1948), from the lumbering John Wayne. Hawks claimed he told Clift that if he quietly watched the action from behind his tin coffee cup, he could steal every scene.

Clift carved out a space all his own. Late in his career, the tremor in his voice and a wary tilt of the head gave him antiheroic quality, as in Wild River (1960). Not for him the over-underplaying of Brando or the unpredictable gestures and dialogue cadences of James Dean. He has his own method, not The Method.

One of the many merits of Making Montgomery Clift, a fascinating documentary by Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon, is that it triggers such thinking about the actor’s craft. Emerging from a hillock of papers, home movies, video tapes, and audio tapes, the film documents two dramas–that of Clift’s life, and that of the process through which complex human beings get flattened into media clichés. As a bonus, we reap many insights into how actors shape their performances, sometimes against the grain of the script they’re handed.

On the life, we learn that Clift was often a buoyant, bisexual fellow, not the brooding and moody figure of legend. He was also a demanding artist who turned down juicy parts. When he signed up for a role, he insisted on vetting the script and sometimes rewriting it. In split-screen Clift and Demmon present the page on the left, scribbled up with Monty’s notes and excisions, and then run the scene alongside. The excerpts they give us from The Search and Judgment at Nuremberg show how a committed actor can strip an overwritten scene down to an emotional core.

If nothing else, Making Montgomery Clift shows us how performances shape movies: the actor as auteur. But it’s exactly this analysis of craft that’s missing from most film biographies. Those doorstep volumes revel in scandal and exposés because publishers think that a straightforward account of hard-won artistry–the sort of thing we routinely get in biographies of composers or painters–don’t suit movies. The result is glamor, excitement, sad stories, and banal interpretations rolled into one fat book.

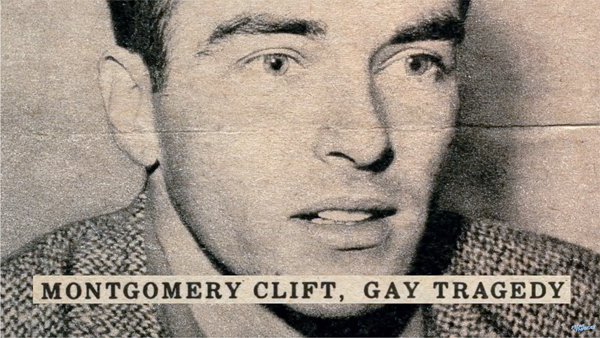

This is the other drama so patiently traced by Clift and Demmon. They show how two 1970s biographies set a mold for the Tragic Homosexual story that has dogged the Clift legend ever since. Just as they pay attention to the movies, they provide close readings of passages in the books, and the evidence of sensationalism, inaccuracy, and offhand speculation is pretty damning. One description of Clift’s injured face after his 1957 car crash savors brutal detail. And it’s not just the ambulance-chasers; passages from John Huston’s autobiography also radiate bad faith.

Clift understood that cookie-cutter journalism would oversimplify him. Thanks to the endless tapes he and his brother Brooks made of their phone conversations, we hear his quick condemnation of “pocket-edition psychology.” There’s a continuum between the tabloid headline, the talk-show time-filler, the celebrity memoir, and the bulging star bio. All try to iron out the wrinkles. During the Q & A, Robert Clift talked about traditional biographies as exercises in taxidermy: “It feels so real because it’s dead.” Hillary Demmon remarked that they wanted to “open up Monty to more readings.”

Making Montgomery Clift proves that academic talk about the “social construction” of this or that isn’t hot air. The film ranks with Errol Morris’s Tabloid as combining a fascinating life story (full of, yes, drama) with a serious argument about how celebrity culture reduces that story to captions and soundbites. Let’s hope the film makes its way to wider audiences, in theatres and on disc and streaming services. It belongs in the library of every college and university, so that students can get acquainted with an extraordinary performer, appreciate the art of star acting, and witness how the media shrinks people to less than life size.

In the crosshairs of history

Like other baby boomers, I’m a connoisseur of conspiracy theories. But we have an excuse. Today’s kids grow up with school lockdowns and street shootings; we had assassinations. Patrice Lumumba (1961), Medgar Evers (1963), John Kennedy (1963), Lee Harvey Oswald (1963), the Freedom Summer murder victims (1964), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968), and Robert Kennedy (1968): this cavalcade of killings made political life seem a theatre of Jacobean intrigue.

Not the least of these was the 1961 death of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld. Hammerskjöld had pressed for peace in the Middle East and was a patient advocate for decolonization in Africa. En route to the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga, his plane crashed. For years many people, including former President Harry Truman, believed that the plane was shot down in order to murder Hammerskjöld.

So of course I had to see Mads Brügger’s Cold Case Hammerskjöld. It did not disappoint.

At first it seems cutesy, with the filmmaker dictating his findings to two African women typists, who occasionally turn to question him. He’s both pedantic and flamboyant (wearing white clothes to match the habitual outfit of a villain he will expose). In contrast there’s the veteran Hammerskjöld researcher Göran Björkdahl (on the right above beside Brugger). Björkdahl is a steady presence as the men question witnesses to the crash and then, crazily, set out to dig up the site. When they’re forbidden to do so, you might think that we’ve got another film about not making a film.

Instead, in the spirit of Morris’s Thin Blue Line, the story we’re investigating drifts into another story, and then another, as documents and witnesses and people who refuse to talk to the filmmakers lead to some appalling charges. Let’s simply say, to preserve the film’s shock value, that the Hammerskjöld case reveals SAIMR, a white supremacist militia for hire. The most horrifying claim about SAIMR and its leader is broached by a well-spoken mercenary purportedly haunted by guilt. His claim has been contested by researchers (as reported in the New York Times). Even if his charge doesn’t hold water, though, the existence of SAIMR seems well-documented.

We conspiracy theorists are often told that history proceeds by accident, not by intention. Yet some intentions succeed splendidly (viz. the killings itemized above), and some succeed by luck. Perhaps the darkest intentions chronicled in Cold Case Hammerskjöld were too crazy to be implemented. But that doesn’t lift responsibility from the feverish minds who dreamed them up, or from the institutions–perhaps mining companies, perhaps MI6 and the CIA–that gave them a hand. In an era when white supremacy has come on strong, Brügger’s film will remain the provocation it was intended to be.

One more entry will talk about still more films at this festival which so generously spoils us.

Thanks to film festival coordinators Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, Zach Zahos, and their dedicated staff for this year’s wonderful event.

Cold Case Hammerskjöld.

0 comments:

Post a Comment