Each morning I wake up, stumble from my bed to the bathroom, and confront the slob in the mirror. He’s put on some weight, and he ponders how many layers are required to hide that fact from others. His chin is not as separated from his neck as it once was. The hair is a wreck, and it will remain so no matter what combination of shampoo and conditioner he slathers up there. He wonders, “Would a beard fix things?” Nah. Quit fooling. This beast is you, and he smiles at the atrocity you’ve created together.

On my darkest mornings, I imagine mirror-me penetrating beyond his frame a la Ash Williams in Evil Dead 2: “We just cut up our girlfriend with a chainsaw. Does that sound fine?” No. No, it does not. Nothing is fine. We’re a hell of our own making. We all want a Necronomicon to blame, but the only fool responsible for the mess you’re living stares you down every day in the mirror. He’s a jerk, and you hate him.

The world is an awful place. Get Out recognized it to be such, and targeted the grotesque system that grinds its wretched gears. Jordan Peele knows there are villains to blame, but in Us, he is spotlighting our culpability for the nightmares we witness on the television every damn day. The monsters on our doorstep wear our faces, and we will die by our own hands.

Doppelgängers have creeped me out since I was a little kid. The image of your double acting beyond your control is primordially scary and speaks to the guilt we hold deep within ourselves. Mom knows about those cookies I stole from the top shelf. Gulp. Does she know about the money I also pinched from her wallet? If she does, then she knows my true self to be a gnarly, snaggletoothed Cro-Magnon brute. I’m not Dr. Jekyll; I’m Mr. Hyde.

The first double I ever encountered in cinema was the Beta Unit android sent to Earth as a placeholder for Alex Rogan (Lance Guest) while he was out saving the universe as The Last Starfighter. The faceless unit is dropped in his subject’s bed, rolls around in Alex’s filth, and replicates his appearance. His poor younger brother knows something is wrong from the jump, but it takes several awkward exchanges, and a few more uncomfortable make-out sessions before Alex’s girlfriend catches on.

The Beta Unit means well, but he also resents his status in the world. Why should he be stuck with all these boring meat sacks while Alex is playing hero amongst the stars? Thankfully, his main purpose is served when the Kodan Armada dispatches an assassin to take out their great enemy, and Beta gets his moment as sacrificial galactic champion. While he’s ultimately revealed to be one of the good guys, the image of a sibling replaced by an artificial lifeform was enough to deliver a few sleepless nights.

Superman III is a terrible film. Not a lot of people will argue on its behalf. At least, it’s not as bad as Superman IV. That being said, Clark Kent (Christopher Reeve) getting demolished by his demonic Superman double after a dose of synthetic Kryptonite creates the two personas is worth the price of admission. What happens when an all-powerful, selfless god-man falls victim to desire? With no Ma and Pa Kent morality to steer him, Superman is a creature of base emotions. Me mad, me punch.

The sequence is ridiculous but utterly compelling to a child. Poor weak Kent bumbling about a junkyard, taking hard punches to the face but refusing to let his inner bad guy prevail. The image of Clark Kent strangling evil Superman to death atop a pile of scrap metal absolutely ruined the ideal of truth, justice, and the American way. A part of me would never trust the spandex boy scout again. If the Beta Unit’s biological takeover prevented sleep, the destruction of that ideology forever altered my belief system. Thanks, Superman III.

While it is scary to consider the demon that might lurk beneath your flesh, it is just as unsettling to consider the purer version of yourself. Insert the cliche: the road not taken. Ernest Dickerson‘s Tales From The Crypt: Demon Knight does not get enough love. The siege film that sees a group of hapless nobodies squaring off against Billy Zane‘s unholy armies of hell is a gorgeous-looking biblical horror that offers a feast for its character actors to chew on.

The moment in which Zane’s Collector entices Jade Pinket Smith‘s Jeryline with images of herself galivanting across the globe is a heartbreaking attack. Join me, and I’ll give you the world you’ve never seen. Betray your friends, and I’ll show you the star you were always meant to be but are too afraid to reach towards. If The Collector had tried this tactic a little earlier in the film before his minions revealed the true beauty secrets of hell’s followers, then maybe Jeryline would have taken the bait. As is, even the possibility of what-might-have-been or what-could-be is not enough to woo her to the darkness. Score one for the big G.

That question of the better you is a haunting earworm. Once it roots inside your head, it gnaws and gnaws and gnaws. If only I were a little more confident. If only I were a little bolder in my actions. If only, if only, if only… Charlie Kaufman could not figure out how to crack his screenplay for Susan Orlean‘s The Orchid Thief. He didn’t see an in until he wrote himself and his imaginary twin into the story itself. From there, Adaptation became not just a saga of creative turmoil but one in which the writer flayed every nagging aspect of himself. It’s ugly, it’s brutal, and it’s relatable.

Tired of bashing his head at the blank page, Charlie (Nicolas Cage) invites his twin brother Donald (also Nicolas Cage) to assist in the formation of the plot. The invitation forces Charlie to engage with his inadequacies as he witnesses his carefree double connect immediately with the material, offer absurd adjustments, and encouragement that literally forces the pair into the action of the narrative. How can Charlie be a better person? By being Donald. Who doesn’t actually exist, but also, yeah, he totally does. He’s you stupid.

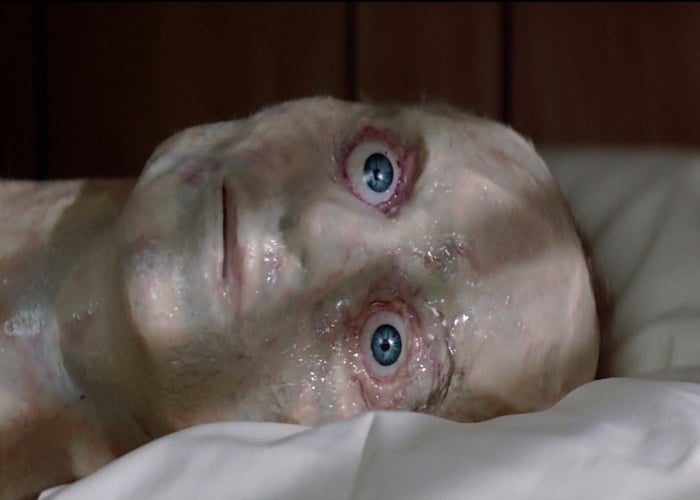

We spend a lifetime building ourselves. We like to believe we know who we are. I’m me. You’re you. John Carpenter‘s The Thing introduces an alien threat that drops from the skies, crawls into your skin, and replicates your self so well that maybe you don’t know who or what you are. Watching another walk around in your body is one thing, but not knowing if you are you is a terror kicked up another three or four notches. When you can no longer trust yourself, you are officially lost.

While Kurt Russell may never confront a body double, he and the rest of the folks trapped in that arctic station are forced to reevaluate the man in the mirror. The alien infection throws everyone in doubt. Carpenter refuses to end the film with an answer. Instead, just enjoy the dread of two maybe-men sitting around a campfire. Are you the thing? Am I? Let’s sit, wait, and see. Whatever your answer to those questions determines how you see the rest of the universe. That depressed lump that meets the mirror most mornings is pretty sure The Thing is the end of us.

The post The Monster in the Mirror appeared first on Film School Rejects.

0 comments:

Post a Comment