Brown Derby lunch menu.

DB here:

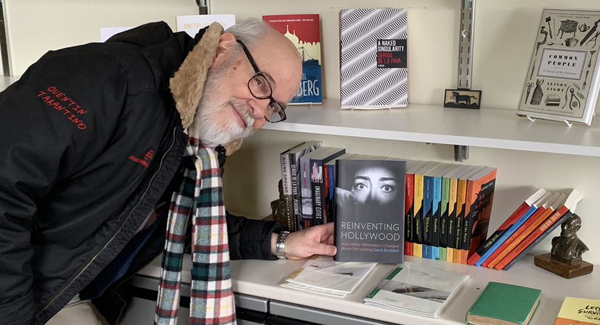

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted at some point. I hope these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

Prosperity helps the movies

Lobby, Loew’s theatre, Rochester, New York, 1940.

Apart from studies of single creators, film historians have often sought to go macro, to tie the films to a broader cultural context. Elsewhere on this site I’ve criticized claims that films directly reflect national character, zeitgeist, or a mood of the moment. There’s no denying that films bear the traces of the societies that make them. The question is how to understand that process—and how to explain it.

I vote for seeing cultural material as filtered through the constraints and choices of the institutions that filmmakers work in. Writers, directors, producers, and other participants (deliberately or unwittingly) pick out bits of cultural flotsam and reshape them. Buzzy ideas become plot premises. New technologies fulfill old functions. The newspaper-headline montages of the 1930s are replaced by shots of chyrons and cable news feeds today. Stereotypes become characters-sometimes unstereotypical ones. Not reflection, then, but refraction, with agents and social institutions recasting some trends that are out there.

But the macro level shapes cinema in another way: as a set of economic and technological preconditions. Around 1900, a society without a market economy and access to machine technology couldn’t have invented cinema. Before the smartphone, people living in certain countries lacked the infrastructure to access the Internet.

Historians sometimes distinguish between proximate causes—factors we can trace with some specificity—and distal causes, those more basic and pervasive preconditions that provide a background for the proximate causes. Along these lines, I wish I’d drawn on Robert J. Gordon’s 2016 masterwork, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

Thanks to the Great Depression, FDR’s recovery scheme, and the start of World War II, both the American economy and most American lifestyles improved dramatically. Home electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, radios, telephones, central heating, cheap clothing, sanitation (no more horse droppings on Main Street), the rise of life expectancy, and the fall of infant mortality transformed everyday life. Most of these improvements were tied to the growth of cities. As Gordon puts it:

Except in the rural south, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940. Urbanization brought fundamental change. The percentage of the population living in urban America—that is, towns or cities having more than 2,500 population—grew from 25 percent to 57 percent. By 1940, many fewer Americans were isolated on farms, far from urban civilization, culture, and information.

Reinventing Hollywood emphasized the boom in movie attendance that took off around 1940. Surely American migration to cities fed into this.

The growth of the film industry in the early and mid-Forties parallels a surge in everyday circumstances as well. By 1950, 92 percent of households had a motor vehicle. Penicillin and streptomycin had begun to drastically reduce instances of pneumonia, rheumatic fever, syphilis, and tuberculosis, while a new vaccine eliminated polio. And the rural population continued to dwindle, particularly when people were lured by the fat paychecks in war-related industries.

Did the diffusion of the major consumer technologies through American society directly affect the form and style of the films? No. Just as the struggle with the Axis didn’t demand flashback structure or voice-over narration, neither did the economic forces in society at large. But they did provide a basis for a leisure economy in which filmgoing could flourish, especially when the war cut down rival entertainments and provided more discretionary income. I discuss these processes at some length in Reinventing. Likewise, radio technology didn’t automatically create new narrational devices like voice-over and auditory flashbacks. Radio’s creative artists chose to develop specific techniques to achieve immediate ends. The rise in American standards of living is not a proximate cause but a powerful precondition for the 1940s surge in innovative storytelling, I could have signaled that factor more strongly.

Hanging out

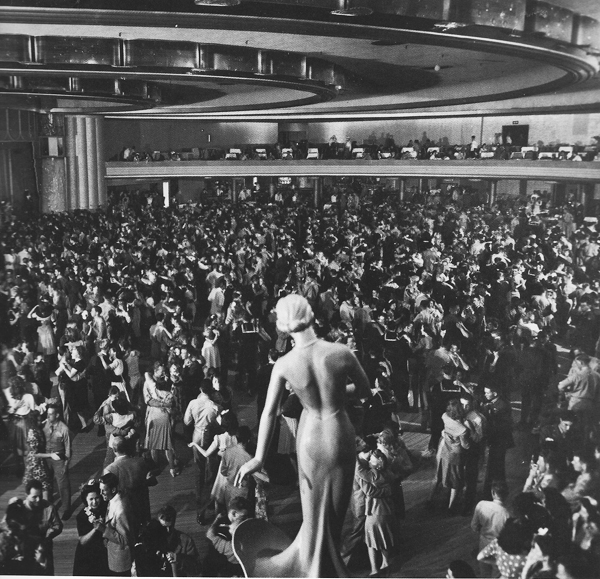

Hollywood Palladium Café.

If the bottom-up approach I tried out is to get anywhere, it needs to show that there’s a community of creators aware of what other folks are doing. Accordingly, the first chapter of Reinventing argues for the importance of Hollywood as bristling with social networks that facilitated cooperation within competition.

Formal organizations, which Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I traced out in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, include professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These served as clearing-houses for filmmaking information. Reinventing adds in the more informal ties among personnel on the job or outside work hours (partying, playing cards or polo). In that era of loanouts and independent production, people who socialized might wind up working together.

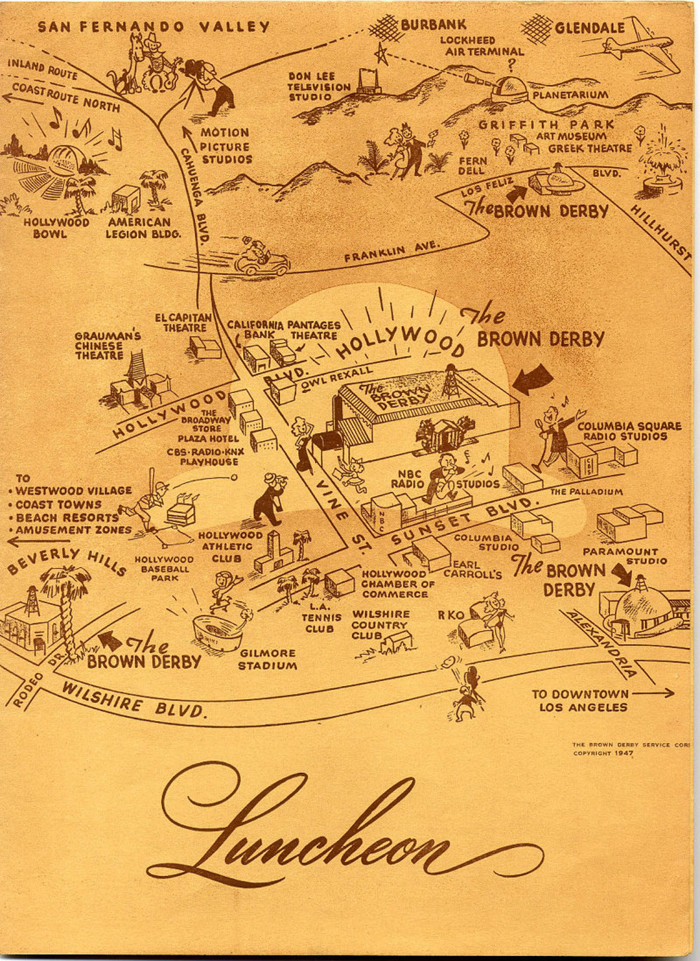

I mention a few Hollywood hangouts, but now I wish I’d done more with the night spots that sprang up in the 1930s, most notably the Hollywood Derby, the Cocoanut Grove, and the Trocadero.

Most of the watering holes lingered into the Forties, when new attractions like Ciro’s and the Mocambo were added to the list. There were some more risqué ones, like Club Zombie and Florentine Gardens, which advertised topless/ bottomless performers. And there was the vast Palladium café, with a dance floor that could accommodate 7500 people.

These and many more venues are featured in magnificent photos in Jim Heiman’s Out with the Stars: Hollywood Nightlife in the Golden Era. Yes, everybody is shown smoking cigarettes.

I did edge into this area by discussing Breakfast in Hollywood (1946) as a network narrative. It features Bonita Granville, Zasu Pitts, Spike Jones, Nat King Cole, Hedda Hopper, and, I’m told, the mothers of Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. The movie was a spinoff of a current radio show that broadcast from Sardi’s before moving to a dedicated venue on Vine Street. An enormous sign promised “Glorified Ham and Eggs from Pan to Mouth.”

The minimal switcheroo

Reinventing Hollywood surveys flashbacks, subjectivity, voice-over, ellipsis, multiple-protagonist plots, and other techniques. They were taken up widely and explored in various directions.

But they weren’t brand-new. Apart from voice-over, of course, these storytelling strategies appeared fairly often in the silent era. And although the 1930s largely swerved away from these strategies, they did pop up occasionally. I discussed several examples, such as The Power and the Glory (1933), The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), Peter Ibbetson (1935), and the crazed Poverty Row item The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

Tom Gunning reminded me of another important precursor. Confession (1937), a Warners melodrama starring Kay Francis, tells of a young woman becoming the prey of a suave but rapacious composer. When she leaves a supper club with him, he’s shot by the woman who has just performed a song. In the singer’s trial, she reveals that he seduced and abandoned her and that his target is her daughter. The court goes fairly easy on her.

The tale is told through some devices that would proliferate in the 1940s. Voice-over monologue to let us in on a character’s thoughts? Check, although it’s very minimal. Flashback to illustrate trial testimony? Check, although that was already a fairly common option from the silent era onward. And a replay of events that show us an event from different viewpoints? Check, although another trial drama, the RKO Ann Harding vehicle The Witness Chair (1936) had pursued the same strategy. (It can be found as far back as The Woman Under Oath (1919), as discussed in an earlier entry.)

What makes Confession more interesting, as Tom also told me, is that it’s a maniacally close remake of Willi Forst’s Mazurka (1935). Here Pola Negri plays the avenging discarded lover. Joe May was a very talented director, but in Confession, he was content to copy the original scene for scene, and sometimes shot for shot. A portion of the German version’s first shot is re-used in the beginning of the American film.

The courtroom is one of several sets that are more or less replicated. Again, the Mazurka shot is first.

Both versions include a replay of an earlier scene. In the first instance, the daughter is unaware that her mother hovers in the hall outside. In the replay, we’re attached to the mother watching the young woman with her adopted mother. The parallel Mazurka sequences are on the top, the Confession ones below.

May’s remake supports a couple of points I made in the book. One source of Hollywood’s 1940s narrative ambitions was foreign cinema. French, German, and British films were exploring these techniques in the 1930s, and some relevant titles got exported to the US. A few were remade, with The Long Night (1947), based on Carné’s Le Jour se lève (1939), being one of the most famous. At the same time, some European directors, like May, started working in Hollywood. Julien Duvivier, for example, leaped into the new US trends with Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

Hollywood endlessly recycles material, as the new Star Is Born shows. Remakes weren’t as common then as they are now, but they did exist. We might see them as part of the process that includes the switcheroo, the habit of varying an existing premise or gimmick with a change that makes the thing look fresh. I suppose the most famous switcheroo comes in His Girl Friday (1940), where the male protagonist of The Front Page (1931) becomes a woman. Neatly, the name Hildy Johnson works both ways. Even Lydia can be seen as a switcheroo on Duvivier’s own Carnet de bal (1937). Everything, as we know, is grist for the Hollywood mill.

Most broadly, popular entertainment exemplifies what I call the variorum impulse, the urge to tweak or twist existing materials and devices. The aim is to produce something new that’s at once novel and familiar. More on the Variorum in a later entry.

Bing and Bob

I’ve had reason to praise Gary Giddins elsewhere on this site, but I never got around to talking about the wonderful first volume of his biography of Bing Crosby. Now he’s come up with Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years 1940-1946. Of course he deals with the musical career in definitive fashion, but just as important for me is his in-depth coverage of Der Bingle’s movies.

McCarey sold Crosby on the part as if he were peddling a modern High Concept project: “You’re going to play a hep priest.” Giddins carefully traces how the film took the country by storm and led to Crosby’s new, extraordinarily powerful contract with Paramount.

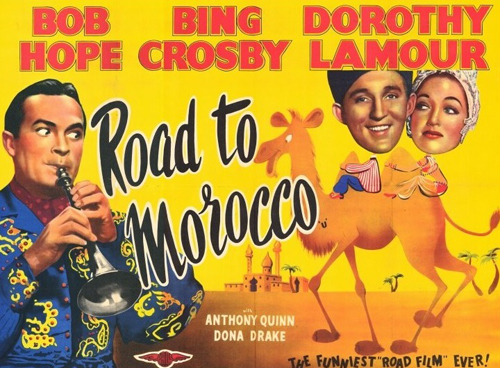

Bing enters my book in Chapter 11, as partner to Bob Hope in the zany Road films. These, along with other Hope vehicles, exemplify for me the acute movie-consciousness we find throughout the 1940s. Of course silent films and early talkies were often set among moviemakers (one of my favorites is Boy Meets Girl, 1938). But the theme shifted into higher gear in the 1940s and early 1950s, when we got films that exhumed Hollywood’s history (The Perils of Pauline, 1947; Singin’ in the Rain, 1952) and comic films that made fun of cinematic conventions. The latter is most wildly illustrated in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), but we get comparable cinematic in-jokes in the Road movies.

Giddins leads us behind the scenes, showing how the Road scripts, tentatively approved by the Breen Office, would get pulled apart during shooting and naughty bits of impromptu got shoved in in.

The writers aimed not only to make scripts funny but also to bamboozle censors. As Bing and Bob crisscrossed the set between takes, like fighters going to their corners, they would receive whispered zingers from personal gagmen, each star looking to unbalance the other; the constant comic rigor roused players and crew. Breen had no knowledge of the ad libs or how scenes would play.

Giddins is constantly throwing crosslights on these films. He shows, for instance, that the “high-velocity raillery” of The Road to Zanzibar (1941) owes something to producer Paul Jones, who had worked on Preston Sturges’ comedies. “The pace of the dialogue between crooner and comedian is impeccable, unforced, and funnier than the actual lines.”

To greater or lesser degree Giddins plumbs all the fourteen films Crosby made in these years, weaving them into the spectacular radio, touring, and recording career of one of the most popular stars in American entertainment. There’s plenty of sadness to go around too.

I could go on and on, as you know. After I finished the book I discovered George S. Kaufman’s 1945 play Hollywood Pinafore; or, The Lad Who Loved a Salary. It uses Arthur Sullivan’s score for H.M.S. Pinafore to mock the movie capital. Here’s a sample featuring the gossip columnist Louhedda:

Somehow all the weekly checks/definitely hinge on sex./ One man fills another’s shoes./Hard to tell whose baby’s whose./ Many autographs annoy/ Ella Raines and Myrna Loy./Goldwyn claims that all our ills/ Can be traced to double bills.

Et cetera. A bit labored, but cute.

Next time: Reinventing Hollywood and Happy Death Day 2U.

Thanks to Tom Gunning, Dan Morgan, Ally Nadia Field, Jim Lastra, Richard Neer, Jim Chandler, Mike Phillips, and Gary Kafer, as well as those who attended my lectures at the University of Chicago in January.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Yow.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. What a brain fart. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Sad!

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Steven Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

UChi marketing guru Levi Stahl tweets: David Bordwell stops by the office but refuses to pose with his own book unless you also let him include Richard Stark’s Parker novels in the picture. It’s as close as I’ll get to greatness.

0 comments:

Post a Comment