True Stories (1986).

DB here:

In the decades since, Blue Velvet has received luxurious DVD and Blu-ray treatment. True Stories, however, wasn’t well-served by Warners’ offhand DVD transfer. Now the Criterion people have given us a lustrous Blu-ray edition of another movie that shows that the 1980s weren’t all big hair, padded shoulders, and John Hughes pity parties. This will quickly become a fetish object for the vast True Stories cult. Visit us way down in the codicil for details.

This movie has been a favorite of mine since I saw it in 1986. Kristin gave me a 16mm print for a long-ago birthday. I’ve wanted to write about it for years, and the Criterion release provides a nifty opportunity. (Full disclosure: I’ve done work for the company. Fuller disclosure: I happily paid for this Blu-ray.)

But I realize that music is so ingredient to the sneaky pleasure of this film that I need expert help. Hence this entry will be followed by one by Jeff Smith. Jeff, as you probably know, is our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our FilmStruck/Criterion series Observations on Film Art, as well as being a frequent contributor to the blog. His deep knowledge of music will yield an entry you’re sure to find interesting.

Many true stories

In the film’s publicity Byrne was at pains to claim that he drew the narrative material from tabloid articles he collected over years of touring with Talking Heads. These clippings supply the initial characterization of the lovelorn Louis Fyne, the Lazy Woman lolling in bed, and the Culvers who never speak directly to each other. Other aspects of the film come from fringe culture more generally, like conspiracy theories and extraterrestrial communication. (The Computer Guy sends signals “up”; in a cut scene available on the Criterion release, he’s transmitting New Age music to be picked up by aliens.)

At the end of the published screenplay, Byrne admits that he used these and other faits divers as inspiration more than as well-documented material. Is this stuff true? “I don’t even really care. . . . It seems to give the movie an extra little bit of excitement to think that maybe it could be true.” The dossier he collected includes not just weird anecdotes but articles about prefab architecture, the computer industry, the malling of America, and other social developments. These are just as important “true stories” as any tales from The Weekly World News.

Do all these stories add up to A Story? Sounding a bit like Wim Wenders, Byrne notes: “Movies are a combination of sounds and pictures, and stories are a trick to get you to keep paying attention.” So he began with drawings, which he posted on walls and kept shuffling around. Eventually two screenwriters, Beth Henley and Steven Tobolowsky, pulled a plot out of them, but Byrne went on to fragment that considerably. The result shifts between episodic and classically plotted cinema.

True Stories has a clear time frame: four days, from Wednesday to Saturday night in and around the fictitious town of Virgil, Texas. This period is followed by an indeterminate gap, ending in epilogue showing a wedding and the Narrator’s departure. The whole tale is framed, beginning and end, by the solfège song of a little girl on the road. Jonathan Demme told Byrne that a movie needs a clock, so the plot creates a soft deadline, the variety show on Saturday.

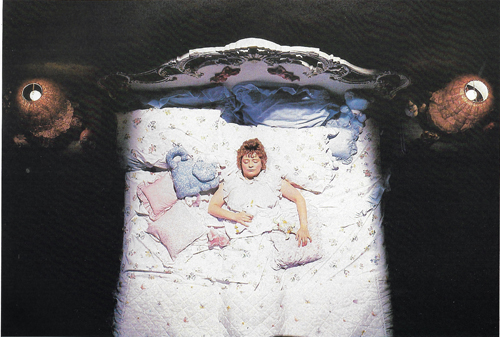

We get something like a tandem story line. First, there’s Louis Fyne’s quest for a woman to marry. More casually, we explore everyday life among the locals. Mostly these revelations come through the wanderings of the Narrator, a lanky outsider dressed in cowboy clothes nobody else wears and possessed of hesitant curiosity. At times, without his guidance, we get other glimpses of town life, such as the habits of the Lazy Woman and the divination powers of her servant Roberto. There are also some very brief vignettes on the margin. The big show ties up the romance line of action when Louis’s stirring performance of his song, “People Like Us,” rouses the Lazy Woman to propose to him. Despite Byrne’s desire to avoid “too much story,” I think most viewers are grateful for a fairly tidy plot that helps us engage with these offbeat characters.

Our Town (not)

Because of the film tries to survey small-town life, it’s been compared to Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, and it seems that Byrne considered that one model. Still, the differences are pretty important.

Our Town concentrates on two families in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire. People live close together and duck into each other’s kitchens and stop to gossip in front yards. But in Virgil there’s mostly no there there. That town is seen chiefly in empty night vistas, lit by blinking traffic lights. Only the parade seems to energize the fairly sparse main drag.

Virgil is hollowed out; all the big stores relocated to the mall. This is the new Main Street, the Narrator explains, and even the music club sits among boutiques and chain stores. Elsewhere, people’s homes homes squat in splendid isolation, like the Lazy Woman’s mansion, or in half-finished developments pasted against a desolate horizon. People have to reinvent themselves in new spaces, we’re told; the cloistered community of New England hasn’t been rebuilt in the exurbs of the New Southwest.

Hence the importance of driving scenes, of which the film has some of the most beautiful in all of cinema. The Narrator cruises the flat, baked landscape, the sky reflected gorgeously in the sheen of his red convertible. Without a car, you can’t join the community, and the Sesquicentennial Parade boasts its share of customized transport, from the Low Riders to the Red Mustang Shriners.

Our Town builds its action out of work and family routines, ceremonies marking marriage and death. The pathetic fate of Simon Stimson, the church musician, warns of the perils of solitude. The romance of George and Emily shows that marriage at least provides companionship and at most nourishes devotion. Across three days separated by years (and with a flashback to a fourth day), Wilder tries to put this entire mundane rhythm into a cosmic context, a cycle of birth and death that should teach us to appreciate each precious instant of life.

So too, in its way, does True Stories. But here the work routines are post-Fordist: Earl Culver explains that people don’t differentiate between working and not working. He’s thinking of techies like the Computer Guy, who ransacks the mall for equipment to tinker with at home. But the blue-collar employees get into the 24/7 spirit. They make their day on the assembly line as casual as lunchtime, talking about love and money and quirks, even crooning to one another. Louis in the Clean Room can spare a moment for a monologue about his love life. At the bar and the mall, the same workers cross paths. In Greater Virgil, leisure is an extension of the break room.

The only family we see in detail are the Culvers, who under a surface perkiness play out rigid roles (and the parents don’t talk to one another). The Cute Woman and the Lying Woman seem to want more, as both meet Louis on dates, but neither can really break out of her obsession (smiling, lying). Even Louis’s eventual mate, the Lazy Woman, gets out of bed only to phone him. After the wedding he has joined her under the covers, presumably to watch TV forever.

Death haunts Our Town, and the same goes for True Stories in its original form. In the screenplay and footage shot, the Cute Woman dies during the parade (overcome by the sweetness emanating from the babies on display). The film’s final scene would have shown her funeral, where the Narrator shares thoughts with Roberto. Byrne deleted her death and burial as too sad, thereby also losing her melancholy Molly-Bloomish bed monologue. (These scenes are in the supplemental material as analog video; below are production stills.)

In a way, the burial would have rounded things off. While Louis’s quest for a wife is rewarded, the Narrator’s inquiry into Virgil’s not-so-wild life could have ended with his discovery of a death from pathetic obsession. It would have been marked by the Lying Woman’s pointless lie: “She was my best friend. . . . We had so much in common.” The comic grotesque would have become the pathetic grotesque.

Excising this scene leaves a gap. After Louis’s wedding (which the Narrator doesn’t attend), the Narrator is seen simply driving off and reflecting on why he likes to forget. Denying us a farewell between the two characters who have built up a friendship in the course of the film, expelling the foreign visitor back to the road and the horizon, Byrne gives us another flavor of sadness. Their encounter was as transitory as everything else in this post-Our Town landscape. And as we’ll see, the Narrator’s meditation as he drives off carries a burden as important as the postcard addressed to “The Mind of God” in Our Town.

Virgil’s guide

Our Town’s Stage Manager is omniscient. He knows everything about Grover’s Corners, past, present, and future. (He predicts the death dates of some people as he introduces them to us.) He indeed stage-manages the action, calling on experts and even summoning George and Emily to reenact their courtship. Yet although he can interact with characters, he can stand outside the story and address us directly. His presence comes to seem comfortable and reliable. He’s an all-controlling guide—at least until the climax, when Emily takes over the narration and tries to return to the world of the living.

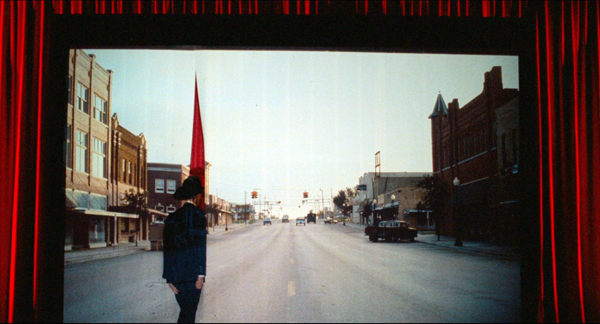

The Narrator of True Stories doesn’t stage-manage anything. He starts out omniscient, lecturing to us about the history of Texas and the occasion for Virgil’s celebration. But once he steps through the slit in the screen, he mostly becomes a naïve, passive presence. He quizzes locals as they deliver monologues, and he seems politely puzzled by their outrageous claims. His dude-ranch getup and geeky silhouette make him almost childlike. He marvels at all the nicknames for highway drivers and is staggered when he sees a four-car garage. (“Who can say it isn’t beautiful?”) The film is almost over when he assures us that this is not a rental car: “This is privately owned.” Who ever thought to ask? And now that you mention it, who does own it?

True, the Narrator issues grown-up pronouncements about the Varicorp chip-assembly plant, but it’s in the bland tones of a PR brochure. He gives us stray factoids like a schoolboy proud of memorization. Even his pronunciation (“special-ness”) suggests either ignorance or awkward efforts to be cute. He might be the incarnation of the voice in one of Byrne’s Knee Plays (“Social Studies”):

I thought that if I ate the food of the area I was visiting

That I might assimilate the point of view of the people there

As if the point of view was somehow in the food….

When shopping at the supermarket

I felt a great desire to walk off with someone else’s groceries

So I could study them at length

And study their effects on me

What sort of narrative authority is this?

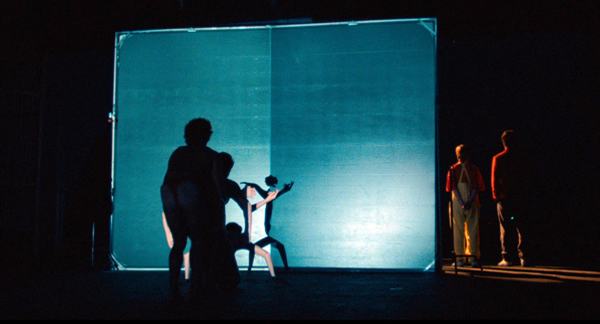

A sort, I think, we find in the calculated vacancy of post-Pop art culture. It’s the blankness of (Texan) Robert Wilson’s po-faced theatre spectacles, where counting off numbers and metronomic gesturing suggest behavior “on the spectrum.” It’s Jeff Koons, maker of gilded Michael Jacksons, saying, “Removing judgments lets you feel, of course, freer, and you have acceptance of things, and everything’s in play, and it lets you go further.” It’s above all Warhol, who perfected affirmative blankness in art and life.

I’m not more intelligent than I appear. . . . The world fascinates me. It’s so nice, whatever it is. I approve of what everybody does.

It’s an artistic strategy that invokes what Viktor Shklovsky called “defamiliarization” and Brecht called “estrangement.” The aim is to make us perceive ordinary life afresh, without the preconceptions we normally bring to it.

For Wilson, repetition and abstraction in the glowing stage box resensitize us to the unique signatures a body traces in space. For Warhol, and his decadent successor Koons, what gets “estranged” is contemporary mass culture, images of Elvis or soup cans or electric chairs or achingly cute balloon bunnies. We’re not far from Romanticism’s cult of the innocent eye, except that we’re not achieving a lyrical insight into nature but rather the thrill of seeing kitsch reveal elusive beauty and unexpected emotion. (I think that this is the point of Tati’s Play Time as well.)

Defamiliarization was of course on Thornton Wilder’s agenda too. Our Town’s bare-bones staging and breaking of the fourth wall aimed at refreshing our perception of stereotypes of rural life. The local-color writers before him had either celebrated small towns (Cather, My Ántonia) or condemned them (Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio), but neither had given them such archetypal poignancy. Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River, we might say, gets redeemed by cosmic purpose.

Like others in the New York art scene, what Byrne sought to defamiliarize was American commodity culture. He had done it throughout the Talking Heads’s songbook, but with a sour, somewhat superior tone. That doesn’t entirely vanish here, I think, as in the moments of satire during Earl Culver’s dinnertime monologue, which becomes a pitch for letting a hundred Silicon Valleys bloom.

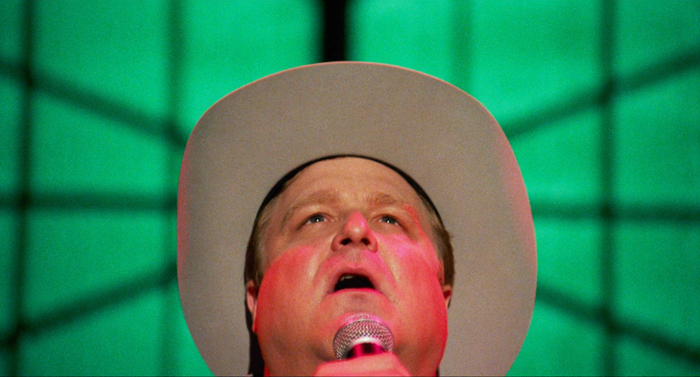

Such mockery is aimed mainly at corporate culture, while the community as a whole gets treated with a more grave affection. Does the sobriety check in the shadow of a Stop’n’Go (up top of today’s entry) owe something to Robert Wilson’s gestural tableaux? The gravity also stems from the planimetric framings, recalling not only Wilson but Walker Evans too.

These angles defamiliarize the landscape of exurbia, and their slightly comic monumentality will be echoed by Wes Anderson and other filmmakers of the 1990s.

As for the affection: I think the gee-whiz acceptance of commodity culture we find in Warhol and Koons becomes something different in True Stories. The good folk of Grover’s Corners, cradled among kin and friends, don’t need to assert their individuality, but the Virgilians define themselves by comparison shopping—and rebranding. True Stories is in part an appreciation of how people creatively remake all the crap pumped out for them to consume.

Amateur virtuosity

None of them seemed to feel alienated. They seemed to respond to mass culture in a very individual way—like, they take a prefabricated house and do something odd with it on the inside. I guess I was sort of proposing that here are these other possibilities—and maybe it was also a little bit of someone from New York imagining these little pockets of Utopia out there.

Near Spring Green, Wisconsin, sits the House on the Rock, a wondrous homage to the maxim “Too much is never enough.” In one hall a pneumatically controlled orchestra plays while you wander among a brewery, a pipe organ, and display cases, while above you hangs the engine of a whaling ship. With its carousels, dollhouses, Titanic souvenirs, and calliopes, welling out of the darkness in spotlights and glowing primary colors, the House on the Rock shows that if you plunge deeply enough into kitsch you come out the other side with something sublime, or at least surreal.

True Stories is in part about that plunge into tackiness, steered by a very 80s concern with the intersection of high and low. Can you endow kitsch with an avant-garde disorientation? Can you infuse avant-garde art with the good dirty fun of kitsch?

Byrne tries. The fashion show blurs the line between inspired tastelessness (a wedding dress like a wedding cake) and PoMo gallery art, the grass leisurewear provided by Bill Harding of Chicago. In the Criterion Making-of, Byrne insists that Adelle Lutz’s costumes are only one step beyond what you could find in Sears Roebuck of the day.

The Red Mustang Shriners, genuine as can be, constitute straightfaced populist eccentricity in a House-on-the-Rock vein. So do many of the variety acts, such as the Apache Belles and the eerie Shadow Dancers. And Mr. Tucker’s bungalow is actually the home of artist Willard Watson (aka The Texas Kid); footage of his encounter with Pops Staples is featured in the Criterion disc. This is another way the title levels with us: Many of the disconcerting images and sounds we encounter are as true as any story.

Some of the moments present authentic local music, like the accordion number in the Tex-Mex club where Ramon performs. Yet more often Byrne navigates the meeting of high and low in a striking way. While artworld-based Performance Art was going mainstream in the 1980s, Byrne starts from the other end and gives highbrow legitimacy to outsider performance art.

Virgil’s routines and ceremonies become occasions for impromptu performance. Instead of a traditional Happy Hour dance competition, there’s a lip-sync contest (“Wild, Wild Life”), with performers using their body to spin associations off the lyrics. A fashion show gets its own catwalk waltz, and a sermon on conspiracy theories becomes a stomping gospel tune. (It provocatively incorporates video clips assaulting the blue-sky tech promises of Earl Culver and Varicorp.) The Talking Heads music video “Love for Sale” absorbed TV commercials; now the film makes the video part of the flow of ads and programs on the Lazy Woman’s monitor. In Virgil, a parade can be a variety card, and a talent show can be as off-kilter as a string of pieces in a SoHo loft.

Amateurism isn’t necessarily clumsy; it has its own virtuosity. Why shouldn’t auctioneering be a sort of rap? Why shouldn’t children enact a love story with ventriloquist dummies? Why can’t people on the prairie come up with mysterious shadow choreography? At the climax, Louis is able to channel his search for love into a country and western song that he belts out with a confidence we haven’t seen from him before.

“Ideally,” Robert Wilson told an interviewer, “what we’d like to do onstage is to present ourselves.” The songs in True Stories, Byrne said, aimed to

give relatively placid people—like you or me—a justification for being vibrant and full of energy, for expressing themselves and exposing their insides to everyone else in the town.

Yet an audience isn’t necessary. Late at night a businessman dances alone at his office window, and a carpenter takes the empty stage to sing an aria. At the beginning and end, on the endless road, a little girl murmurs a song and makes mesmeric passes at nothing. She expresses herself in a fusion of naïve art and Downtown minimalism: It’s at once childish warbling and a Meredith Monk tune.

Our (favorite) town

That song stands out as a sort of primal beginning of all the film’s performances. It becomes the orchestral underpinning of the Narrator’s introduction to Texas history and his first trip down the expressway. The same spirit emerges in the 4H kids’ spontaneous brick ballet “Hey Now.” Childhood, it seems, is media-free, back to the basics of bodies and castoff noisemakers.

The kids’ direct expression is starkly different from the media-enabled activity we see among the grownups. One character, Ramon, is associated with radio; he thinks that each of us transmits our feelings on wavelengths he can pick up. Naturally, he’s written a song about it. The Lazy Woman, on the other hand, is identified with television, her main contact with the outside world.

Mr. Tucker is an LP aficionado; the Computer Guy works on early digital sound. Documentary film is represented as a collage of Puzzling Evidence. Print media surface as the sensational tabloids read by the teenagers.

The sensational stories in the tabs, the wellspring of Byrne’s film, shape the Lying Woman’s confabulations. Grover’s Corners was never plugged in to the flow of information like this.

All these factors—the mix of avant-garde and down-home artmaking, the nutty byways of populist performance art, people responding to a multimedia environment—heighten the effect of estrangement. The film’s opening montage has an arch knowingness, anachronistically mixing Raquel Welch cheesecake with dinosaur lore. Call it comic defamiliarization. But things grow more sincerely felt as we go along, so that the crazy grotesques of Virgil become not so crazy or grotesque after all. Many are waiting on love.

The Narrator, a tenderfoot in a Stetson, is curious and unflappable. His puzzled acceptance of everything that comes his way encourages us to forget what we think we know about hayseeds, the sovereign state of Texas, high-tech industry, suburban sprawl, prefab buildings, and dorky parades. The last we hear of him, he’s already deleting the file, but I doubt we can.

Well, I really enjoy forgetting. When I first come to a place I notice all the little details. I notice the way the sky looks, the color of white paper, the way people walk, doorknobs. Everything. Then I get used to the place and I don’t notice those things any more. So only by forgetting can I see the place again as it really is.

In the film’s final moments, the Narrator’s confession of Warholian passivity turns into a defense of defamiliarization that could have come from Shklovsky. “Art,” he wrote, “exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.” We can perceive true stories only by stripping away our preconceptions.

Byrne the creator has suggested that the film allowed him to find his way back to emotions beyond comfortable irony. “It was hard to go around not liking everything.” We can debate a long time why the end of Louis’s song, “We don’t want freedom/ We don’t want justice/ We just want someone to love,” both shocks and satisfies us. (Today, a Deplorable would change only the lyric’s last word.) But as an expression of sheer self-presentation, it’s hard not to sympathize with this Texas Bachelor.

Although the Narrator can forget, we don’t have to. According to the final song, we can remember this as our favorite town. With this film, Byrne makes sentiment safe for hipster consumption.

Working with Byrne and DP Ed Lachman, producer Kim Hendrickson and her team have supervised a brilliant 4K edition, the first time the film has been presented in 5.1 sound. They’ve included some precious material culled from new interviews, period footage, and excised scenes. There are also informative essays by Rebecca Bental, Joe Nick Patoski, Spalding Gray, and Byrne. The making-of is the best example of the genre I’ve ever seen, and the documentary on Tibor Kalman is quite informative on Byrne’s visual imagination. (The Criterion cover art is one of Kalman’s rejected designs.) One bonus short is a piece of analog video shot behind the scenes; another, by Bill and Turner Ross, is a contemporary return to the places shown in the film.

The film was shot full frame, to be masked in projection; some video versions displayed it at 1.37:1, others at 1.85:1, which is the one presented here. Kim was assisted by technical director Lee Kline, and audio supervisor Ryan Hullings. Also very helpful in the restoration and supplements was Christina Patoski, who organized a large portion of the original production. Many participants supplied photos and notes for the film’s preproduction.

Most of my quotations from David Byrne come from the Introduction in the book of the film: True Stories (New York: Penguin, 1986). Byrne’s remark about pockets of Utopia is quoted in Michiko Kakutani, “David Byrne Turns His Head to Movies,” New York Times (5 October 1986), 92.

The Warhol passage comes from Gretchen Berg, “Nothing to Lose: Interview with Andy Warhol,” Cahiers du cinéma in English no. 10 (1967), 40-42. The Robert Wilson quotation comes from Calvin Tomkins, “Time to Think,” in Robert Wilson: The Theater of Images, 2d ed. (Harper and Row, 1980), 84. The Shklovsky quotation is in “Art as Technique,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. Lee T. Lemon and Marian J. Reis (University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 12.

True Stories.

0 comments:

Post a Comment