The HBO Max comedy An American Pickle is about many things: intergenerational conflict; tradition versus modernity; different approaches to grieving; how much money a Brooklynite will spend on a single pickle (apparently $4). The film follows an Eastern-European Jewish immigrant who falls into a vat of pickles in 1919 and wakes up perfectly preserved a century later. Seth Rogen plays dual roles, first appearing as that forward-time-traveling immigrant, Herschel Greenbaum, and then also as Herschel’s great-grandson, Ben Greenbaum. With a keen sense of visual humor, the contrast between the two characters makes a satirical look at how the world has changed and what we can do to honor its past.

As Rogen mentioned in a New York Times interview, he and screenwriter Simon Rich (whose short story “Sell Out” also served as the basis for An American Pickle) kept returning to the same idea while making the film: if our ancestors saw how we lived and behaved today, would they straight-up just hate us? This is the core struggle between Herschel, a tough-as-nails ditch-digger with a history of escaping violent pogroms, and Ben, a freelance mobile app developer. The film’s predominant visual gag is having two very different lead characters with the exact same face, and it’s most effective when Herschel uses their physical likeness to sabotage Ben, forcing him to take the fall for his great-grandfather’s transgressions.

Brandon Trost, best known as the cinematographer for such comedies as This Is the End and Neighbors, shows an unsurprising knack for visual humor that anchors his directorial debut. But the film’s juxtaposition of the new world and the old world isn’t just evident in its lead characters. An American Pickle also regularly features parallel imagery, with similar but contrasting shots of places that first hold sacred meaning and later are depreciated or modernized beyond recognition. These shots are both startling and funny, showing us how the world has evolved in Herschel’s absence.

There’s a darker element to the comedy in An American Pickle, especially during moments that comment on how the world has changed for the worse during Herschel’s brining years. A century earlier, the small New York cemetery where he bought plots for himself and his wife Sarah (Sarah Snook) was peaceful and pristine, a fitting resting place for two people who’d faced unimaginable hardship and loss both before and after their arrival in America. In the present, the cemetery is in a state of comical decay, backdropped by a noisy expressway overpass and a tacky billboard advertising a law firm. It is unkempt, strewn with garbage and dead vegetation. Even with the burial grounds for Ben’s great-grandmother, grandparents, and parents, this is clearly not a place with a steady stream of visitors.

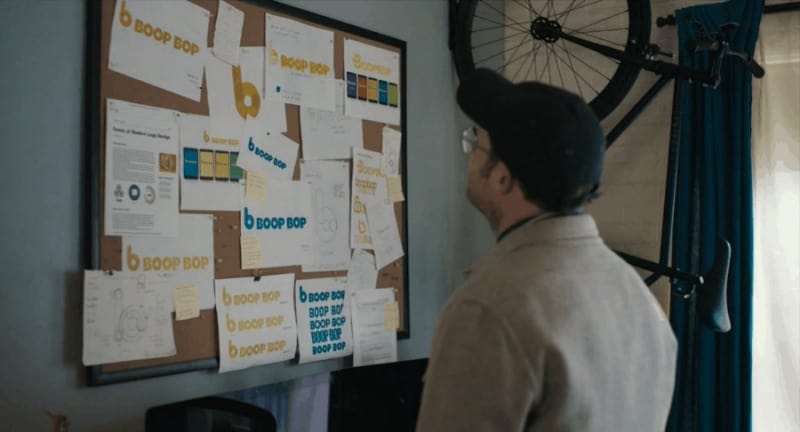

The neglected cemetery is merely the first of Herschel’s qualms with his descendent. When they meet, Ben has been spending the better part of five years working on his app, Boop Bop, the main function of which is to inform consumers whether the products they buy are ethical or not. The joke is that the actual software has been working for a long time, but Ben now wastes his days tweaking the branding: “Companies are made or broken by the color of their logo!” Modern technology saturates Herschel’s new life, and app design aesthetics are perhaps the most profoundly baffling offering. Why does this look so ridiculous, you might ask, as you stare at this shot of Ben’s vision board:

Pre-brining, Herschel’s dream was that his progeny would be successful and well-off, bringing pride to the Greenbaum name. Thus, Ben’s debilitating passivity, best represented by the myriad of barely-distinguishable logos that he claims will determine the fate of his company, becomes a source of contention. “Throw your punch!” Herschel tells Ben, pleading with him to book a pitch meeting. The silly Boop Bop logo tells its own darker story, though, as it’s revealed to be an app named for Ben’s deceased parents, who financed it as an investment in his future. And Ben’s inability to move on from its design is a parallel of his inability to properly grieve his parents’ death.

Where Ben’s story dwells on his inward struggle with the past, Herschel’s serves as a larger cultural commentary about how isolating the present-day can be. When he and Ben get into legal trouble and their relationship turns sour, Herschel starts a pickling business that soon catapults him into the Brooklyn artisan hall of fame. He becomes the kind of overnight cultural oddity that people love to document in pursuit of internet virality and then, when the time comes, to knockdown. Out there in the spotlight, Herschel makes a lot of enemies. To its credit, An American Pickle is probably the only film this year to frame an approaching army of antisemitic Cossacks the same way that it frames an angry mob of Christian students chasing Herschel for making insensitive remarks about the Virgin Mary during an on-campus debate.

The only thing that Herschel can’t outrun is the media cycle, documented through Buzzfeed-like headlines that weirdly objectify him and cable news chyrons that are covering his saga instead of more pressing news. The sensationalist coverage that he receives — as well as the Being There-esque sycophancy — are clever jabs at technology and social media, two contemporary inventions that give massive scale and unearned importance to everything ostensibly personal or trivial. Herschel’s life, so simple and immaterial before he de-brined, is now burdened by the weight of this newfound, intangible form of social capital.

Herschel and Ben eventually realize that they can’t come to terms with their lives — the younger Greenbaum mourning his past, the elder trying to make sense of the present — without leaning on each other. It’s a conclusion best captured by their final scene in Herschel’s fictional home country, Shlupsk, where the two sit by a pond described as “Sarah’s favourite place.” In an early scene, Herschel and Sarah sit by the water. The pondside location is an unremarkable but nonetheless charming sliver of the natural world. At the end of the film, Herschel and Ben sit in the same spot, which now overlooks a laughably grotesque nuclear power plant, ignoring that the pond is now a pool of chemical waste as they remark on its beauty.

Even on the other side of the world, without a single New York skyscraper in sight, Herschel must bear witness to how fundamentally different everything looks. It’s back at the cemetery in Brooklyn, though, where An American Pickle comes full circle. Dignity is restored to the Greenbaum family plot; there is no more garbage and no more high weeds overwhelming the graves. It is now modestly appealing, with the exception of the concrete highway, but this is a compromise that the characters are forced to make. They settle somewhere between the old world and the new one. They have to. Because life goes on either way.

0 comments:

Post a Comment