Double Take is a series in which Anna Swanson and Meg Shields sit down and yell at each other about the controversial, uncomfortable, and contentious corners of cinema. There are many reasons this series started, but the catalyst for having a long conversation to work through dicey topics was a comment made by FSR’s own Rob Hunter. Upon discovering Anna’s deep and sincere love for Rob Zombie’s much-maligned ‘Halloween II,’ Rob remarked that this is an opinion so gobsmacking it must be unpacked. So that’s exactly what we’re doing.

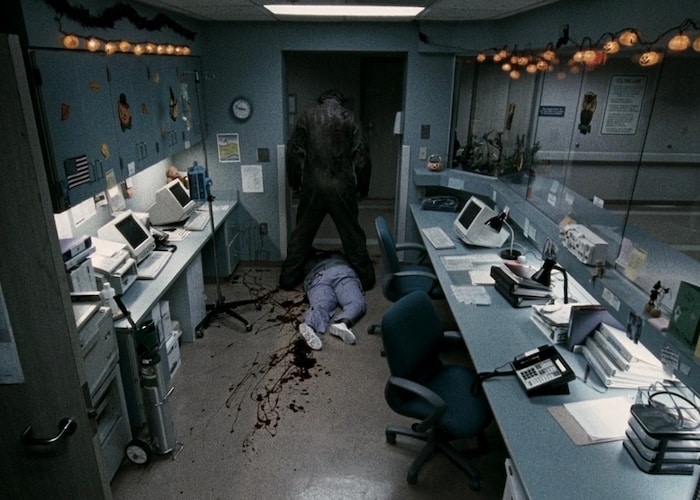

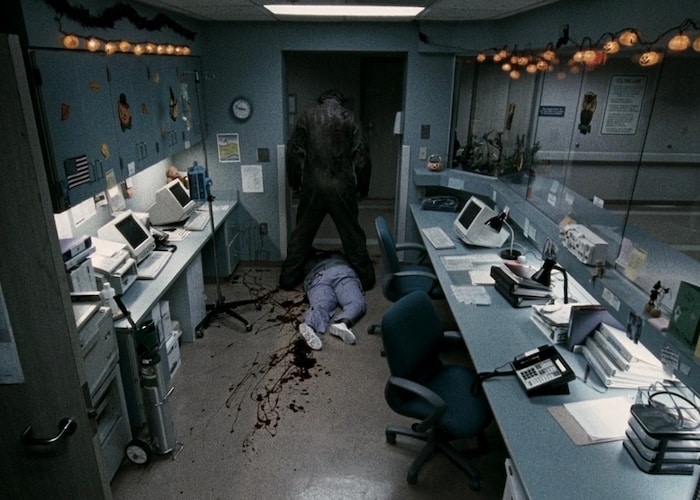

For our first Triple Take, we got Rob on the horn to offer a counterpoint to Anna’s praise for the film. Together, the three of us aimed to work through what makes the film so problematic for some and so beloved for others. Boasting a 21% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the sequel/remake is a gnarly rampage with all the tact that one would expect from a Zombie film. It is more belligerent than Zombie’s 2007 Halloween (which even Anna agrees isn’t a good movie). The sequel tracks the return of Michael Myers (Tyler Mane) and follows Laurie Strode’s (Scout Taylor-Compton) traumatic response to the events of the first film. Halloween II is a film that we all agreed goes for it. The question we were left with was if it’s a gamble that pays off.

Halloween II celebrated its 10th anniversary earlier this year, and with a bit of perspective afforded through time, Meg, Anna, and Rob sat down to unpack this deeply divisive movie. This is the conversation that followed:

MS: I’m not gonna tell you what I think about Halloween II and it is your job to convince me that it is either good or bad.

RH: Why do you assume that I think it’s bad?

AS: That’s why we’re here! That’s how this came about! Because you hate it!

RH: Yeah, ok, no it’s terrible. So no worries about that.

MS: Anna to kick things off can you relay to Rob what happened during our viewing?

AS: Ok, so I tried to show Meg Halloween II

MS: Not correct. You made me watch both of Rob Zombie’s Halloweens, back-to-back.

AS: You needed the context. But what happened was, I hadn’t seen the director’s cut before, only theatrical. I didn’t realize until too late that the director’s cut has a different ending and I was showing her that one. In the director’s cut, Laurie is shot at the end.

RH: Best part of the movie.

AS: [deep sigh]

MS: Rob, is there any part of it that you think is redeemable?

RH: Oh boy…I mean I like when Laurie gets shot. But that aside… give me a minute…

MS: I wrote some down. Brad Dourif is in it, and that’s good because we like it when he gets work. Ummm… I think Scout Taylor Compton is doing something.

RH: Generous, but go on.

MS: I’ll reveal my hand: I think my overall take, and the reason I think it’s such a point of contention, is that it wants to be something that it isn’t. It’s fighting its own genetics. It wants to be something banana pants like The Beyond, just like: total chaos. But Zombie actually thinks he’s delivering realism. If you listen to interviews with him, he thought he was really getting down to it and not producing a wild, nightmare logic fantasy.

AS: I think there’s realism too.

MS: You think this film is realistic?!?

AS: There are moments, but say what you were gonna say.

MS: To me, in all his work, Zombie is hyper-stylized. That’s part of his charm. I can see how if him fighting the zaniness of it all would result in something a little messy.

RH: Are you drawing a line between the beats of the movie that are bad but grounded in “realism” and the bad parts that are fucking Zombie’s wife on a horse? The movie only exists because 1) the first movie turned a profit, and 2) he wanted to give his wife some work. There’s no reason for that character in the film. I should also say I’ve seen all of Zombie’s movies and I’m a fan of one of them: Lords of Salem. The rest of them I either dislike or actively dislike.

MS: I don’t hate Zombie. I’m on record loving House of 1000 Corpses, which I like because I think it actually knows that its bonkers. It’s not so serious. I think Halloween II is very serious, Anna.

RH: The movie is serious as hell, and it falls in line with the first film. I think this is my problem with both films: Zombie is so in love with his killers, his killer in this case, and he so despises the people that Michael Myers is killing. That comes across frame-by-frame. The second one is so serious, it’s devoid of oxygen, of air. There’s no fun or entertainment. There’s no impact.

MS: I’ve seen some people give it credit for being a remake that goes in its own direction, but, uh, Zombie is just doing Halloween IV. All the cool weird parts: the psychic link she has, the genetic component of serial killing–that’s in Halloween IV.

RH: Can I jump ahead and point out that this film is devoid of gory setpieces? There are a face stomp and stabbings…it’s not creative.

AS: I mean…. He has a knife. That’s what he does.

MS: Michael Myers has impaled people with guns, he can be creative.

RH: This is Zombie, he does gory, bloody stuff in his movies. If I’m coming at this looking at the potential for this to be a worthwhile movie, one of the things that you can take away from a horror movie is a memorable kill. There’s nothing in this movie that stands out.

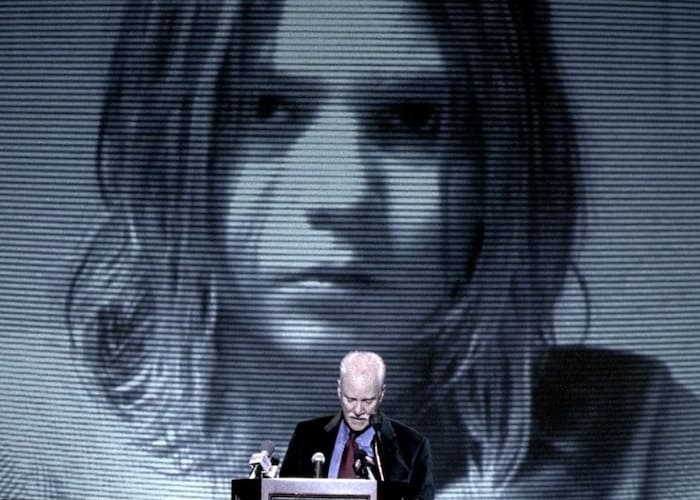

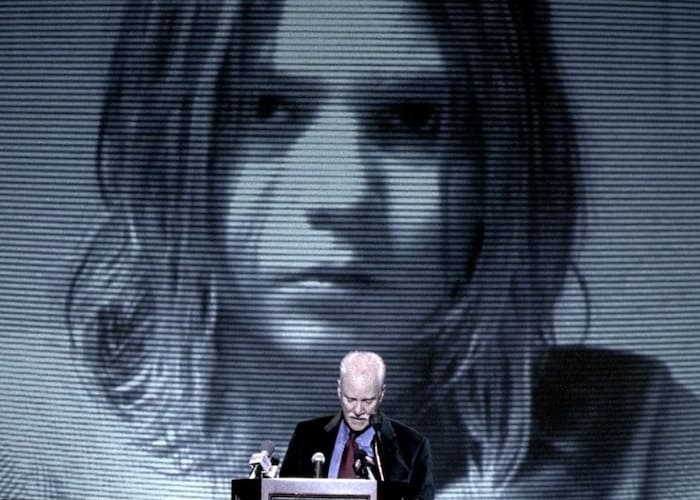

MS: One thing that, Anna did sell me on was the Dr. Loomis angle and the idea of him being a scummy opportunist. You argued that as a good addition and I think you’re right.

AS: Yeah, so, first of all, if you’re gonna get Malcolm McDowell you gotta put him to work. And, I like that it lampoons the true-crime thing of profiting off of tragedy. I like that it shows Loomis as exploitative…

MS: And you can’t replicate Donald Pleasance. I think regardless of whether it’s executed well or not, doing a different thing was the right move.

RH: Removed from the movie, I love McDowell. But Zombie has no grasp on tone, so you move from deadly serious brutality to fucking slapstick with McDowell and the two bits do not go together. He’s comic relief for so much of the movie. It’s designed for laughter and when you smash that up against the rest of the movie, you’re left with two things that don’t go together.

AS: I don’t think it’s slapstick and I don’t think it’s as sharp of a pivot. I think what you’re describing is exactly what happens in Halloween (2018). Sorry: Hallow2018. That’s what it does: it pulls those sharp turns from trying to be horror to trying to be comedy. I think Halloween II maybe has some comedic beats, but they’re not as disruptive of the film’s overall tone.

RH: I should ask before we move forward, do words mean the same in Canadian as they do in American?

AS: [Sighs] Ok, I want to point out regarding the death scenes, one that comes to mind is the scene in the strip club where the dude is strung up by the lights. That’s fun. That’s a good use of a set-piece. But back to Loomis. I like that the jokes are at his expense!

MS: I liked the first sequence in the hospital before the “it was all a dream” rug pull.

RH: It’s an extended dream sequence. That was the first time I said “fuck you” aloud at the screen.

AS: I like the fake-out hospital because it really highlights how much he’s aware of the other films and he knows our familiarity with it but then he’s going in a completely different direction.

MS: But he’s still just doing Halloween IV! Zombie missed the boat on picking up at the beginning of II instead of the end of IV.

AS: Wait, what? In what way do you want that?

MS: I want a small child…being murderous. Look, Anna. Defend your movie.

AS: Ok, alright, I like how fresh it is, it does something new. I do think there’s a tension between the surrealist fantasy and the brutal realism but that works. There are killings that feel very real. When Annie is being murdered and she’s just saying “ow” over and over again, it’s for-real upsetting. It’s not this shrieking horror movie yelling, it’s real fucking pain.

RH: I had that in my notes. Annie is the only character in either film that I, as a viewer, feel anything towards. But, that said, they turn around in this movie and treat her the same way: she’s brutalized and left naked on the floor. Cutting away from the video and just having the audio, I do think is effective, I’ll grant it that. I just feel like it doesn’t work in this movie because you wait a few minutes and you’re laughing along with Loomis, “hyuh hyuh hyuh.” If Zombie had kept it a brutal slasher I would respect it a lot more. But these beats, I don’t care about the Annie stuff with everything else.

AS: I think we do care about Annie, partly because we see how much she’s all Laurie has. And speaking of Laurie—

RH: Let me just say: I’m not a fan of Halloween (2018), and I did appreciate that Zombie — poorly and shittily — made an effort to explore the trauma. To a degree, I was down for that. The problem is that he makes a traumatized person into a character who won’t stop screaming, who is obnoxious. And again, I can’t judge her because she’s been through trauma, but we’re still stuck for 110 minutes with this person and nothing to latch onto. I appreciate the attempt, but it gets lost in the execution. It’s better than what they did with Halloween (2018) and the handling of trauma.

AS: Yeah, that’s exactly what I was gonna say. I like how much Halloween II is about trauma and how much it commits to bleakness. There’s no real way out of this. There’s no happy ending. It’s a big commitment to make a film that’s kinda mean and upsetting. I really respect that it doesn’t pretend she’s gonna find a real solution. By making her so erratic, we know she won’t end this film on a positive note — no fucking way. I like that Zombie makes us sit with that knowledge.

MS: Right but like: Zombie wants to be Michael Myers, or likes him a lot. I think that gets in the way of what you’re saying…

RH: He absolutely sympathizes with him. If you go back to 80s horror movies, a lot of them are built on the idea that the person who ends up being the killer was bullied or had some prank committed against him. But this is something that’s dealt with in the first few minutes and then it doesn’t get touched on because it’s not important. Zombie just focuses on that and wants to keep reminding us of that. He’s clearly in Michael’s corner. He’s more interested in that character. As a film, it ends up being an experience where, as much as people criticize later Elm Streets or other Halloween movies for how they allow you to root for the killer, Zombie takes that, removes all of the fun and says, “Yes, that’s what we’re gonna do, we’re gonna support the killer.” He’s brutalizing people left and right, but that’s ok because of the shit from his past. So, for there to be no happy ending for Laurie, it’s because Zombie looks at her pain as “this is what this family is. This is reality and there is no escape.” I don’t mind movies that end on a complete downer, but if from the beginning it feels like this is gonna be shitty for everyone involved, there’s no entertainment value. There’s no suspense. There’s no emotional connection. I don’t know what I’m left with.

AS: The fact that I view Laurie as doomed doesn’t remove an emotional connection for me. I think Zombie does spend time with Michael, but because it’s not fun. I don’t think we’re supposed to enjoy it. If it was more fun to watch him kill people then I would be on board with criticizing how much Zombie likes Michael. I don’t think just because the film expands on his backstory that is the same thing as supporting or sympathizing. To me, it’s about understanding what Laurie is experiencing through this connection to him.

RH: Huh. I mean, I disagree obviously. But, to that connection, do we agree that the vision of his mother is not supernatural shenanigans, but a mental vision? There’s a later scene where they both react to the same vision. This vision of his mother, and it’s not really her character. Going back to the first movie, she was compassionate towards her son. She was taken aback by his actions. So this vision is not one based on memory. It’s there to support Michael’s psychopathic agenda. It’s imagined. My point is that this supports the idea that Zombie just wants to give Michael excuses. The vision is supporting him. It’s another thing telling him he’s right to be doing this.

AS: Exactly. That’s not a real person supporting him. The vision is part of his psychosis. It’s him inventing reasons. This is about how disturbed Michael is–not about someone else giving him the green light or to detract from the fact that he wants to do this.

MS: But it’s not Michael inventing an excuse, it’s Rob Zombie inventing an excuse for Michael. I think it would be better if the movie just went full-on buck wild rather than try to be serious. It wants to have its cake and eat it too.

AS: But there’s a method to the madness because what is actually happening is brutal and visceral and upsetting and real. But as Laurie is losing her mind, her experiences are becoming increasingly messy and surreal. It’s how she is perceiving events not how they actually are.

MS: You don’t think the psychic link exists?

AS: I think Laurie thinks it is real. Laurie is losing it, she’s feeling this inability to move past Michael, and that’s informing her mentality. She feels that there’s a reason she is so tied to Michael. Maybe there is, maybe there isn’t. But that’s how she’s experiencing it.

MS: [exacerbated] You’re contradicting yourself.

AS: No, what I’m saying is that there is a realism and there is a fantasy. The actual real events are done in a very brutal way, the violence is honest and real. And then Laurie’s mental space is being filled with fantasy and surrealism because she can’t process what’s going on in the real world, so she turns inward. She’s having a psychotic break. It doesn’t change the world around her. When she sees a horse, there isn’t really a horse. But when Annie is killed, it is real and upsetting.

MS: I still feel like you, like Zombie, are trying to have it both ways. Can we talk about the party? The big party that Zombie clearly wanted to throw for all his friends?

RH: I thought it was a wrap party and they were just shooting extra footage. It’s this weird-ass little town where you can have an ambulance crash into a cow, and then you have this huge-ass Hollywood party.

MS: See, I like that. It’s stupid. It’s like a Fulci movie; a small town but then there’s a ballroom down the street for some reason.

RH: Yeah but in a Fulci movie it never also tries to be real.

MS: That’s correct…

RH: So in Halloween II, it stands out because it’s supposed to be hardcore and real but now here’s this gibberish. Also, do you think Zombie is supporting a nature over nurture hypothesis?

MS: I’m glad we got to this point. It’s gotta be nature.

RH: I think that’s what he’s saying, especially with the fact that she’s having these shared visions and is connected to Michael.

AS: But she’s having these visions after enduring the trauma, so that’s kinda nurture.

[Rob and Meg make confused noises]

AS: I think in terms of Laurie going full fucking fantasty, that happens after the trauma of the events of the first movie.

MS: Right but Annie didn’t go off the deep end and she experienced quite similar trauma.

RH: As the film kept reminding us.

AS: Different strokes for different folks! People respond to trauma differently. There’s no one size fits all! Annie has a great dad! That helped her!

MS: So…nature?

AS: Well no. It’s the support that Annie’s had.

RH: [giggling]

AS: I mean, I do think that there is an element of nature over nurture, but I don’t think it’s like, a hard and fast one hundred percent.

MS: But canonically it is right. [laughing] That’s the whole point of Halloween IV.

RH: But so we agree on this: that at the end of the film when she [Laurie] goes to stab Loomis–I guess you could argue that that’s strictly because he wrote the book–but still that’s a homicidal act. She’s not going to stab Michael who’s killed all her friends, which clearly she doesn’t care that much about as she does her reputation.

AS: In the theatrical cut she does stab Michael.

RH: So, is the director’s cut ending supposed to suggest that she survives the shooting? Because much like the nature element, that her brother Michael can survive multiple bullet wounds, she also has inherited that ability since at the end of the film she’s in an abnormally long psych ward. Is that what we’re supposed to buy?

AS: I think she’s in her own mind. I don’t think what we’re seeing exists in the real world at all at that point. I read the end scene of her in the hospital room as a complete fantasy happening as she’s dying, imagining moving on to the next world by reuniting with her family.

RH: I can see that. Again, that room is obviously not real-size. It’s clearly a dream room. But I’d also argue that filmmakers with these kinds of movies are always going to make sure that they’re ending allows the possibility of a follow up. So you’ve got to keep the person alive. But it makes more sense to me that she’s dead and this is just a mental snapshot.

MS: Rob Zombie’s Halloween III when?

AS: [visibly excited] I would love that. I would prefer that over more David Gordon Green movies.

RH: I would happily pass on both.

AS: Rob, if you had to pick if you were to get another Rob Zombie Halloween or another David Gordon Green Halloween, which would it be? One is going to exist, which is it?

RH: [struggling] I would, uh, I feel like this is going to underscore everything I’ve just said, but I would take the Zombie one. From beginning to end, Halloween II clearly shows a filmmaker with an artistic intent and, to a degree, an ability.

MS: You can accuse Zombie of a lot of things, but not of not making choices. That man makes choices.

RH: They’re just in service of a shitty, shitty script.

AS: I will concede that I think he could have pulled back on some of the comedy with Loomis. That wouldn’t have hurt the film at all.

RH: [presumably raising his hands up in celebration like an inflatable tube man] Score!

AS: But I do think that what he is doing for the most part with the Loomis character, of showing him as someone exploitative, is good. I like how much he goes after Loomis for that.

MS: I agree. I think Zombie’s take on the Loomis character that holds water.

RH: I would agree as well, I just don’t think that the execution works or comes together well enough in this movie. I think that he’s a smart target to go after, but I would have loved to have seen all of those sequences played straight with him being fucking criticized, lambasted, given shit, for what he’s doing. The closest we get is the dad who shows up at the book signing with a picture of his dead daughter from the first movie. Everything else with Loomis is comical. It’s played for laughs, through both his performance and the beats. Weird Al Yankovic…

MS: I forgot about the Weird Al part. [groaning]

RH: Yeah. That whole scene reminds me, in one of the Nightmare on Elm Street films there’s a talk show sequence. I can’t remember which one–

MS and AS, simultaneously: Are you thinking of Joker?

RH: No. Anyway, all that Loomis stuff is so comical it loses a lot of the bite that it deserves. It loses its punch because it’s like “woop-de-doo look at this little funny bit over here.” It doesn’t land as well as it should.

MS: I haven’t seen the new Halloween.

AS: Don’t.

RH: It’s so bland.

MS: Does it bring anything new to the table that can hold a candle to the wacky shit in the Zombie films? LIke does Hallo2018 have anything new to say, and if so, are any of the new twists as bold as what Zombie did?

AS: No.

RH: I would agree. No.

AS: There’s one idea in it that I’m especially annoyed it squandered. There’s a true-crime podcast about the Myers murders. And when I saw that I was like “oh, there’s potential there.” Like this is of the moment in the horror world and you could do something interesting with it. And then it’s not at all. In any shape or form.

RH: I don’t hate the 2018 remake but I do find it kind of harmless and safe. It does have some good kills using some fun practical effects, so it has that going for it. And I know everyone lost their shit over the grief and trauma angle, but it’s not that at all.

AS: It’s very simplified.

MS: There are so many horror remakes that I constantly forget exist. I think that even the people who really don’t like Halloween II would never accuse it of being non-existent or forgettable.

AS: Yeah like the Nightmare on Elm Street remake with Rooney Mara.

MS: Or like, remember when they remade Poltergeist in 2015?

AS: No I don’t.

MS: No one does! I think for all of it’s sins, Halloween II is doing something.

RH: I think that’s the definite take-away because even though I don’t like either of Zombie’s Halloween films, they’re not like the vast majority of these “safe” remakes, that don’t try anything new or stick too close to the original.

MS: Or try and please everyone.

RH: Right. Like fan service and that kind of stuff. At least Zombie is like: I have the basic structure down. Now I’m going to do my own thing. With the second film more so than one. I don’t like it, but I can give it some begrudging respect I guess.

AS: Rob, do you like Zombie’s Halloween II more than his first Halloween movie?

RH: I don’t like either one of them.

MS: That wasn’t the question.

RH: Two is the [groaning] more ambitious film.

MS: That’s like a parent being like “you looked like you were having a lot of fun up there.”

RH: Halloween II is still bad. But it’s got elements that are still worthy of discussion.

MS: Now I’m just thinking of all the “not safe” directors I wish were given blank checks to fuck with properties the way Zombie was. I’d prefer that timeline over the mayonnaise we’re getting from most studios. I’d love to see someone fuck with Child’s Play in a way people had to have an opinion about. The remake has come out, allegedly. No one’s talking about it. It’s a nothing movie. It doesn’t exist.

AS: I’d rather hate something than be completely apathetic.

RH: Absolutely. The fact that I had any kind of feeling whatsoever, even though its negative, is impressive. Child’s Play, you go in you go out. Even the Pet Sematary remake I was just like okay. There were changes but they weren’t bold like the ones Zombie has made. I do think it’s interesting, cause a lot of people, especially with Zombie’s last few movies, keep talking about how it’s so unfortunate that he’s not getting a big budget, and for both Halloween films he had 15 million bucks each. It shows. The money is on screen.

MS: Yeah he blew it on that party in Halloween II and then he was like: “Michael, take my wardrobe.”

RH: Exactly. But I think it shows that he, as much as I prefer the bold choice timeline, had the chance, and it was this.

AS: Yeah, and god bless. He did a great job.

RH: Do you actually think that this is a great movie? Halloween II?

AS: Yep.

RH: Okay but real talk. Meg’s gone, she’s getting popcorn and Columbo VHS tapes, is this a great movie?

AS: Yeah. It’s a four-star movie.

RH: Out of how many?

AS: Five.

RH: This is an interesting movie for someone to say is great. For any movie, you’ve got to be on its wavelength and find things that appeal to you…I don’t feel like I fully understand why you think it’s great.

MS: If I may, Anna, is the thing that makes this film “good for you” the way the film takes Laurie’s trauma so seriously?

AS: Yes. And I like that, whether it’s well-executed or not, I like the ambition of it, I like that Zombie wants to do something completely different way.

RH: So you like Halloween III.

AS: Love Halloween III. But yeah I like the way this film is more interested in Laurie’s experience than just using it as fodder to make the film “about something.”

[Authors’ note: Rob was giggling throughout this]

RH: I don’t get the empathy side of Halloween II. Maybe it’s because I’m just an asshole, but I don’t see the effort made. I appreciate what it tries to do with the trauma, and it’s definitely better than Halloween (2018), but I feel like it puts it out there and essentially says: look we’re acknowledging that she’s fucked up. And that’s the end of it. I don’t think it does anything else with her on that subject. Especially with the back half shifting to the dream stuff.

AS: I think if it tried to do more than what it’s already doing with Laurie’s trauma, it would pretend that there’s an answer, and I don’t think there always is.

MS: I don’t think we’re saying that the film needs to fix her trauma. But after she gets past the tipping point, there’s no variation. Do you know what I mean? If the film is dealing with female pain, the lack of emotional payoff is a big problem to the point where it could be read as objectifying her or her trauma.

RH: I don’t think the movie has sympathy for Laurie. I think that it uses her and her trauma the same way it uses Annie and Annie’s trauma. The same way it uses women who are consistently naked in the movie. Not just as sexy beats of women being naked, but as being naked, in their worst moment, and fucking brutalizing them. I don’t need a fix, but the film presents Laurie at her most shrill and says: “Ok, this is just the status quo now.” There are no additional gains there. Instead, it’s just Zombie saying: I’m going to take full advantage, and exploit these characters at this moment, for my cheap thrills because, again, I wish I was Michael Myers.

AS: I can’t disagree with how you read this movie — I read it differently!

MS: This is the truest Double Take. Every other time Anna and I have talked we’ve either come to an agreement or it’s been us against the world. This is the first stalemate we’ve had. I’m excited we’re finally fighting. This is what we wanted.

RH: But what do you guys think about, what I would argue, is the pure exploitation Zombie takes towards his mostly female characters. To me, it’s fine if you’re going for a straight, serious horror film, but that’s not what this is.

MS: Zombie’s entire career is trying to make The Texas Chainsaw Massacre II again. That’s his purpose on this earth. I think the way that he treats women in his films is of a very grindhouse sensibility: maniacs brutalizing shrieking women. I can see the connective tissue between Zombie’s work and his inspiration from the 70s.

RH: But with something like Werewolf Women of the SS, I would love for him to make that full feature movie. That kind of exploitation, Nazisploitation, whatever camp over the top ridiculousness would work. But here, where I take umbrage–

AS: Great David Fincher word.

RH: Nice. Where I take umbrage is Zombie applying that aesthetic, that women are best served naked, bloodied, and terrorized, and pairing it with straight, horrifying, intentional brutality. It’s not like the My Bloody Valentine remake where you’ve got the naked lady running around being chased because that movie is purely silly.

MS: What you’re talking about is self-awareness. Maybe Zombie was too close to Halloween II to have the perspective to see what the film needed. He spends way more time pathologizing Michael than Laurie because, at the end of the day, he’s way more interested in absolving Michael Myers.

AS: I think there’s a difference between understanding and excusing.

RH: It’s explaining.

AS: The fact that Michael Myers thinks he has reasons doesn’t mean that those reasons are good. And I don’t think we need to give Laurie reasons for what she’s doing in the sense that like, we want to empathize with her actions because I don’t think that what she’s doing is wrong in that way. She’s the victim here, right?

MS: I don’t know about Zombie’s lack of care for Laurie being intentional. I don’t think that’s true. And you and I give a lot of fucks about directorial intention so be careful how you proceed.

AS: I buy that there’s a problem with how Zombie presents the brutality against women. I’m not defending it. But I will say that I would rather have something straight-up uncomfortable over something that pretends Laurie’s trauma can be put into a neat box.

MS: You’re using the same move we made in our discussion about The House That Jack Built: that violence against women shouldn’t be treated with kid-gloves and to some degree, should be hard to watch. But that move is only goin if we’re not on the side of the villain. Which is true of Jack in a way that is absolutely not true of Halloween II.

AS: Yeah. And I don’t think this movie is as good as The House That Jack Built! But I don’t think we’re supposed to sympathize with Michael.

MS: I dis-a-fuckin-gree.

AS: What?

MS: This film is in love with Michael Myers!

RH: A comparison for me is something like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. It’s brutal, straightforward, it’s played serious. There’s obviously a little bit of levity in it, depending on your tastes. Henry does give points over to his circumstance to explain where he’s coming from. But at no point does it belittle what’s happening, either through funny shenanigans or fantasy beats, it just lets it be, so you get the seriousness of it. It never feels like it’s trivializing any of it if that makes sense.

AS: Do we read Halloween II as “trivializing?”

RH: That’s my point about the tone. I think if it stuck with the “horror elements,” not the Loomis stuff or the dreams, I’d be closer to your side of the argument. Because when it wants to be brutal it’s brutal. The problem is that whenever I felt the least bit heightened, going back to the Annie beat, I feel like its deflated shortly after that by jumping back to McDowell or having Sheri Moon Zombie show up with her horse. It immediately says: nevermind, there’s also this shit going on. It doesn’t allow you to wallow in the seriousness of it because it keeps reminding you that it’s “a fucking glory project for my wife.”

MS: Oh no. This is a glory project for Rob Zombie.

RH: Yeah, either way.

AS: I see what you’re saying. My experience of the film is different.

MS: “I FEEL.”

AS: I don’t find the tonal shifts as jarring! But that’s subjective and I can’t argue with your subjective experience.

MS: [laughing] Anna, you can’t show up to this dog fight and then be like: “it’s all subjective!”

AS: No, just that specific thing! I’ve made my case on the other stuff.

RH: I’m not sure you’ve made your case, but you have spoken it.

MS: [laughing]

AS: I’ve pled my case how about that?

MS: Do you think in the way A24 has a pit where they keep their waifs, Rob Zombie has a pit with like his wife and Bill Moseley?

AS: A wife pit?

MS: His two wives: Bill Moseley and Sheri Moon.

RH: At least he lets Bill Moseley out once and awhile.

AS: I’ve thought of something.

MS: Ok.

AS: I want to see Rob Zombie make a Cat People movie.

MS: Oh.

RH: [groans]

The post Double Take: Is Rob Zombie’s ‘Halloween II’ Secretly a Masterpiece? appeared first on Film School Rejects.