James Gray‘s Ad Astra feels like a culmination or at least the furthest step in an evolution of an idea. It’s a film Gray needed to make ever since he ventured out of New York City as a kid and really noticed the stars up above. It’s a film depicting man’s farthest reach beyond Earth, both in terms of distance to the edge of our solar system and in terms of technology and scientific research — aided through consultation with experts at NASA, Lockheed Martin, and others. And it’s a film that progresses cinematic sci-fi of a kind that began at the dawn of movies and has led to these close-ups of Brad Pitt‘s emotional trip through space.

Just as Pitt’s character in Ad Astra must layover at different points along the way to Neptune — from Earth to the Moon to Mars to the last planet in our solar system, plus all the little steps within each location — Gray’s movie is a destination in storytelling that needed certain other films to jump off from to get here. For this week’s Movies to Watch After, I’m highlighting those titles that led to the existence of Ad Astra, whether directly acknowledged by the writer/director of the film or not. Venture backward chronologically and make the trip back home with us.

The Lost City of Z (2016)

First stop is the previous film by James Gray. Based on the true story of Percy Fawcett, The Lost City of Z is a kind of companion piece to Ad Astra. There is a significant father-son relationship, and the plot concerns man’s exploration into the unknown. But it’s a venture set entirely on Earth in the near past rather than in outer space in the near future. Fawcett disappeared, along with his eldest boy, while searching for an ancient city of gold hidden in the jungles of South America. Gray has compared the story and setting of the movie to Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness, without the madness, and that novella has now also been a huge inspiration for Ad Astra, as we’ll get to in a bit.

“If you’re able to make films, it’s wonderful that you can rip off your heroes and at the same time try to bring yourself to it,” Gray told Slant about this movie’s comparisons to Apocalypse Now (which is based on Heart of Darkness) and Werner Herzog’s jungle films. “My idea wasn’t to adapt Heart of Darkness, because that exists already. It’s called Apocalypse Now and it’s a masterpiece. The whole approach was to indicate a level of transcendence, a move in another direction. Fawcett at least reconciled with his son…His obsession was rooted in a feeling that he would never be able to articulate his need to escape from the structure of the society from whence he had come. In a sense, Amazonia is simply a stand-in for any place or anything that isn’t England in 1905 that he had to get out of.”

Stream The Lost City of Z on Amazon Prime Video.

Interstellar (2014)

On a surface level, Gray’s movie immediately looked like a successor to Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar as far as modern space movies go. These are works of hard science fiction, concerned more with a mix of character drama and real or plausible science rather than big adventure narratives and action sequences. This one also deals with catastrophic circumstances on Earth that require one man’s journey into space for the sake of humanity but also winds up being an intimate story of reconnection between a father and his child after an impossible mission through the cosmos. As in Ad Astra, the main character doesn’t venture out alone at first, though he is solo by the end. Nolan has even admitted that Heart of Darkness was one of his inspirations for the film.

“I wrote the thing in 2011,” Gray told Yahoo UK regarding how his movie fits with Interstellar and other recent space movies. “Chris Nolan, who’s a very good friend of mine and a great person, is very secretive about his projects. I said, ‘What are you working on?’ and he said, ‘Something space/science-fiction,” and I kind of went, ‘You are?” Then I saw the movie and I got all upset because he was using an organ and he did a bunch of other things I wanted to do. Then Gravity came out with a realistic depiction of space. So the ambition was actually earlier than the films that are out now — and Damien Chazelle’s wonderful [First Man], too. So I didn’t use them in the initial thought process, but it speaks to the interest level of the filmmaking generation. We are now able to look at something like the Apollo mission, for example, with enough distance that we can appreciate it.”

Sunshine (2007)

While Nolan seems to get the credit for moving us forward in this decade’s trend of realistic sci-fi movies, into which we can also lump the historical drama First Man, this movie tends to be overlooked. Perhaps it’s because it came a few years before the present decade. Perhaps it’s because the movie was ignored at the box office. Danny Boyle’s Sunshine does have one of the most disappointing endings compared to its buildup, yet it’s such a stunning movie until then that it’s worth admiring. It’s also a complementary work of science fiction paired with Ad Astra because it’s about another response to catastrophes on Earth caused by something in space, though here the mission is toward the sun rather than farther away from it.

Hey Film Twitter I know y’all are gearing up to pit AD ASTRA against GRAVITY but for the record I am always and forever team SUNSHINE and this is the hill I will die on.

I will not be taking any questions at this time.

— Ciara Wardlow (@ciara_wardlow) September 21, 2019

And yes, this one has a Heart of Darkness connection, as well. “Apocalypse Now is my favorite film, and it’s known as the Heart of Darkness film because it’s loosely based on the Joseph Conrad book. And we always said that our starting point for this film was a ‘Journey into the Heart of Lightness,’” Boyle explained to Slashfilm while promoting Sunshine, which follows a mission to reignite the sun by nuking it. “There are certain rhythmical similarities. It’s a journey and at the end of the journey is a fantastic, a madman who’s seen the light in his own way. Structurally you could compare it to Apocalypse Now which has a similar shade to its journey as far as shape is concerned.”

Solaris (2002)

Why I’m recommending Steven Soderbergh’s Solaris rather than Andrei Tarkovsky’s original is because of George Clooney. Like Ad Astra, this remake of the 1972 Russian sci-fi movie based on Stanislaw Lem’s novel of the same name stars one of the main ensemble cast members of Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven (and its two sequels). There was a gag on social media about the poster for Ad Astra following those of Solaris and the Matt Damon movie The Martian as featuring a close-up shot of an Ocean‘s actor in a space helmet. This later included a nod to Gravity, which co-stars Clooney, because its lead, Sandra Bullock, also led the all-women spinoff Ocean’s 8.

Aside from the extratextual relevance, however, Solaris is also a similar movie with its Hollywood sheen matched with the cerebral contemplation and pace of a foreign film (for the blockbuster-aspiring movie you’d expect Hollywood to churn out as a remake of Solaris, go back to 1997’s Event Horizon). Clooney plays a man recruited, due to a personal connection, to travel through space to a station with which communication has been lost. During his mission, he’s also forced to reckon with the resurfaced existence of a relation he thought was long dead — here’s it’s an apparition of his late wife. Need a Heart of Darkness connection? Lem and Conrad were both Polish writers. Okay, that’s not much, and Tarkovsky’s Stalker is more Heart of Darkness anyway.

Space Cowboys (2000)

The closest Clint Eastwood has ever gotten to sci-fi, Space Cowboys is a movie about a space mission but sticks with what could have happened for real at the time. To an extent. Eastwood directs himself in the role of a retired test pilot needed for an operation involving a satellite similar to one he developed back in the 1950s. For the task, he gets his old band back together in the form of his fellow NASA rejects played by James Garner, Donald Sutherland, and Tommy Lee Jones. Because of those last two being together in this movie and now being old friends in Ad Astra, coupled with the images of a younger Jones in Ad Astra being lifted from this movie, makes Gray’s film seem like an unofficial sequel. The shared casting of Loren Dean as a younger astronaut in both seals the deal.

Stream Space Cowboys on Netflix.

Gattaca (1997)

You’re thinking I missed something by skipping over a certain sci-fi blockbuster from 1998, aren’t you? Well, Space Cowboys is enough of an “okay, I’ll go into space on a mission despite not being an astronaut but only if I can bring my old team with me” film for this list. And there’s really not enough of a significance to Liv Tyler playing a main character’s significant-other left on Earth while the guy goes to space to include Armageddon. Right, so Gattaca. Andrew Niccol’s stylish sci-fi drama doesn’t ever go to space in the confines of its narrative though it’s all about a man with dreams of rocketing off the planet. But due to genetic profiling, he’s deemed unfit to become an astronaut. So he impersonates someone with more “valid” DNA.

I actually hadn’t thought about Gattaca as a candidate for this list until our own Anna Swanson brought it up on Twitter. She sent me this note in Slack, which I’m quoting in full despite it being a run-on because it was only intended to be a DM: “It reminded me of Gattaca mostly in terms of the ending and the idea that people can strive for progress and perfection (Vincent doing everything possible to manipulate his way into the program; Clifford taking the most incredible images of space and Roy making his way to him) but at the end of the day there’s always going to be a need for humanity and kindness and connection that can’t be measured by scientific progress (the other scientist letting Vincent go while knowing the truth, Roy realizing he has to open himself to others and shoulder their burdens).”

Stream Gattaca on Amazon Prime Video.

For All Mankind (1989)

This week’s documentary pick was a difficult choice because of how many great films there are about space and space travel. Including Destiny in Space, which imagines the future of human exploration to Venus, Mars, and beyond. This year alone even there’s the magnificent Apollo 11, which is arguably the best doc of 2019. But while numerous docs on space missions existed already and have come out since, Al Reinert’s Oscar-nominated feature For All Mankind, which focuses on the Apollo program and its Moon landings and features narration from astronauts who lived them, is the standard for the genre. It also served as a key reference in the making of Ad Astra.

“You know that documentary For All Mankind?” Gray asked in an interview for The Playlist three years ago while talking about Ad Astra plans. “The footage is remarkable: they shot all this 16mm footage and [I want to] do it like that.” Earlier this year, Gray was also quoted in a New Yorker article on Reinert, this film, and its connection to and influence on docs like Apollo 11, biopics like First Man, and fictions such as Interstellar and Ad Astra. “For All Mankind was an astonishment,” he says. “The wonder of the Apollo missions had been something of an abstraction for me beforehand—the stuff of lectures and history books. But Al Reinert’s film made it both real and yet, somehow, more mysterious. It is a beautiful achievement, at once epic and intimate.”

Stream For All Mankind on The Criterion Collection.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Apocalypse Now (1979)

More often than For All Mankind, these two seemingly dissimilar movies are cited as the two main reference points that collided in the conception of Ad Astra. Back in January, he got the ball rolling as far as setting reviewers up for some easy comparisons. “It’s very Heart of Darkness,” he said in a TIFF interview. “It’s sorta like if you got Apocalypse Now and 2001 in a giant mashup and you put a little Conrad in there and you hope its as good. But it’s probably not. I’m being silly. But those were the influences.”

He had already mentioned the Conrad influence on his sci-fi project three years earlier. “I started to think about a very Heart Of Darkness/Apocalypse Now thing, that somebody is going to do an experiment like [the one to split the atom back in the 1930s] because they have nothing to lose,” he told The Playlist. “And we have to send somebody to destroy him. So that is basically [what the film] is, and the thing that’s in the middle of it, of course, is the terrible cabin fever that begins to set in.”

Three years prior to that, he was already talking about the project to The Playlist and stated, “I had read about NASA trying to find ‘emotionally — what’s the right word — undeveloped’ people to travel to Mars because being cooped up for a year and a half is very difficult. So the idea that I had was to sort of mix a kind of Conrad-ian story, a Heart of Darkness, with the idea in which NASA has made a miscalculation about one of its astronauts, who cannot handle deep space. So the idea is a kind of mental breakdown in space, and to do it almost like Apollo footage: incredibly realistic — so no sound in space, obviously — and to do it distinguishing itself with the idea that, in a way, human beings need the earth.”

So, yes, here is where Conrad’s Heart of Darkness fits into the history of Ad Astra. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now is a loose adaptation of the novella, resetting the destination in the story to Cambodia during the Vietnam War as opposed to the Congo (there have been TV movies more directly adapted from the book, including one by Nicolas Roeg). From the first bit of narration by Brad Pitt in Ad Astra, I felt the connection to Martin Sheen’s voiceover in Apocalypse Now. And the course of Pitt’s character is an odyssey not unlike the one Sheen’s character experiences on his way to where he’s going. There are more memorable moments and characters in Coppola’s movie, though.

As for the 2001: A Space Odyssey side of the mashup, that’s fairly obvious on a superficial level. Ad Astra is hard science fiction about a mission through our solar system. It similarly stops over at the Moon first and displays a bunch of corporate branding as would likely be genuine with a commercial Moonbase. Ad Astra goes the extra measure, however, with everything from Subway and Applebee’s franchises to a Hudson News. Both movies also deal with extraterrestrial contact — or the pursuit of such at least. Gray started out thinking about making a movie like 2001 before he had the exact story of Ad Astra figured out.

“2001 which is my favorite film in the genre and one of my favorite films ever, is about man’s confrontation with the idea of the infinite and then evolving into a new species when in contact with an alien force,” he told The Playlist in 2013. “So in a perverse way the Kubrick film has optimism — the star child is an optimistic conception. I’m not planning on a bummer movie at all because what happens is the astronaut basically falls in love with someone on Mars, and the rest of the crew find this out. And of course, that’s a problem, because they’ve all been chosen to be incapable of that because they have a mission to execute on Saturn, so as a consequence they have to eliminate him.”

Rent Apocalypse Now from Amazon.

Rent 2001: A Space Odyssey from Amazon.

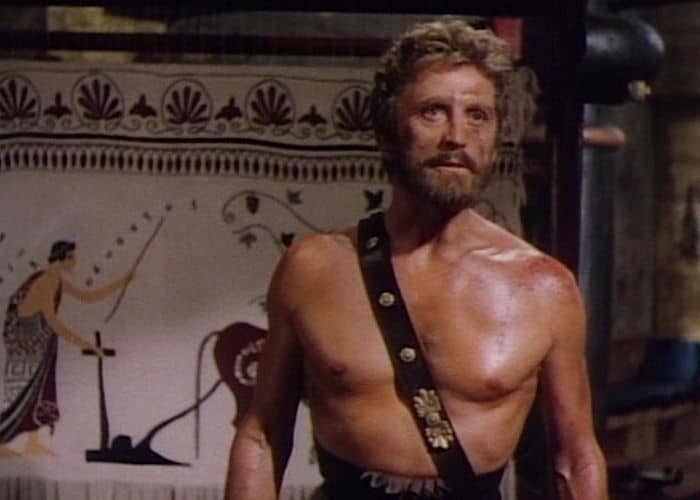

Ulysses (1954)

From A Space Odyssey to Homer’s Odyssey and another non-sci-fi film. What does an Italian adaptation of an ancient epic poem have to do with Ad Astra? And why would I choose this movie over the more recent Homerian film starring Brad Pitt? Well, Troy ends before the events of the Odyssey begin, and that’s the connective tissue because Gray was inspired by Homer’s sequel to his Trojan War-set Iliad. And surprisingly, Warner Bros. never bothered to make a follow-up movie with Sean Bean reprising his Troy role as he attempted to get back home to Ithaca. So we’ve got this one with Kirk Douglas in the lead still as the best possible example.

“We wanted to steal from — as pretentious as this sounds — we wanted to steal from the Odyssey,” Gray told Rotten Tomatoes about the epic poem’s influence on Ad Astra, “and tell the story, really, from Telemachus’ point of view. His father, Odysseus [aka Ulysses], goes away for 20 years; he doesn’t know what happened to him. What that would mean, and that sense of abandonment that Telemachus must have… Now, of course, Homer’s story ends very differently. But that’s where that came from, a kind of mythic idea.”

Orchestra Wives (1942)

Here’s another break from the sci-fi and definite inspirations on Ad Astra. I’m including it near the end here (its chronological place anyway) as a bit of an aside much as it plays briefly in Gray’s movie. When we hear “(I’ve Got a Gal in) Kalamazoo” and then see the Nicholas Brothers singing and dancing the tune in a clip from the Glenn Miller showcase Orchestra Wives, it kind of takes us to another place and time for a moment. It’s just playing on a screen in the Lima Project station, surely the viewing selection of Jones’ character, whom we’d heard earlier is a fan of old black and white Hollywood musicals. There’s no relevance to its selection outside the movie save for the fact that it’s, like Ad Astra, a Fox production.

Buy Orchestra Wives on DVD from Amazon.

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

And here we are at the very beginning for the very end. Georges Méliès’ mashup of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells stories follows — that’s right — a trip to the Moon. It’s widely considered to be the first science fiction film, though that’s not quite true unless we disqualify earlier works involving space travel and aliens as being more fantasy because they take place within dream sequences. Still, it’s the first major release of the genre. A Trip to the Moon also came out the same year as another pertinent piece of pop culture relevant to this list: Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, while published in serial form over a few issues of Blackwood’s Magazine a few years earlier, the story was released, complete, in book form, within a collection titled Youth: A Narrative, and Two Other Stories, in 1902. Just think, that year, you could have gone to see the film and read the novella on the same day and then that night dream of them colliding as one.

Stream A Trip to the Moon on Amazon Prime Video.

The post Watch ‘Ad Astra,’ Then Watch These Movies appeared first on Film School Rejects.

0 comments:

Post a Comment