The Shallow Pocket Project is a series of conversations with the brilliant filmmakers behind the independent films that we love. Check our last chat with Jim Cummings (writer/director of ‘Thunder Road’). Special thanks to Lisa Gullickson and the other Dorks at In The Mouth of Dorkness.

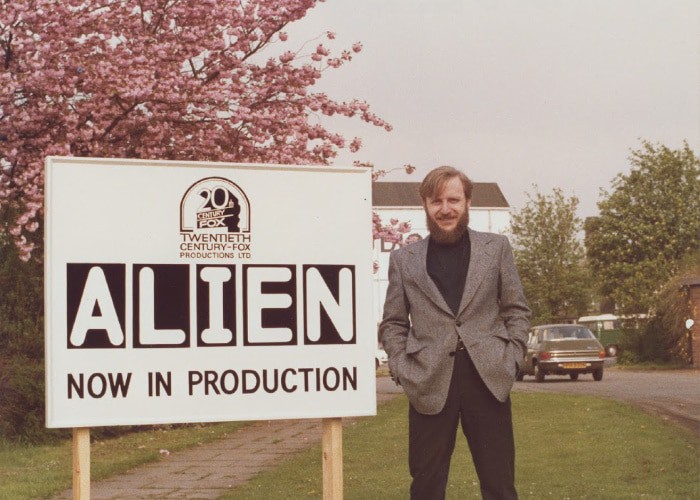

Forty years ago, an alien creature that looked very much like a penis with teeth burst forth from John Hurt’s chest and forever altered the canvas of cinematic science fiction. This brief moment of terror seared into the pop culture conscious, capturing the imagination of a nation and igniting a stream of imitators. Ridley Scott’s Alien is an undeniable masterpiece that mashes many genres and speaks to even more anxieties.

Film is not created in a vacuum. Just look at the end credits. There were hundreds of individuals that threw their passion and craft into those 116 minutes. However, its creative absorption does not end there. Hundreds, maybe even thousands, of artists contributed to the creation of the Xenomorph. From the Greek masters to the works of Francis Bacon to the most pulpish of grim comic books, Alien owes its life to many talents.

Filmmaker Alexandre O. Phillippe has built a career deconstructing the great works of film. His previous documentary, 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene, zeroed its focus on the iconic sequence from Psycho and revealed a national need to exorcize fear. Now, with Memory: The Origins of Alien, the director turns his obsession towards the 1979 sci-fi/horror classic and that infamous dinner table Chestburster. The new film poses a collective erupting to tell this particular story and a society hungry to devour its beautiful horrors.

Lisa and I spoke to Phillippe the day after his film premiered at Sundance. Our conversation begins with the need for long-form cinematic discussions and why his enthusiasm for dissection is more necessary today than ever. Of course, we geek out over all the various contributors to Alien and dig into the very heart of his grand thesis. Alien was birthed from the zeitgeist, and its conception may have been inevitable no matter what filmmaker ultimately put it before the camera.

Here is our conversation in full:

Brad: Right now, film conversation is so short. It’s tweets. It’s sound bites. But here you are with your career, and you’re steering a long-form essay with each film. What started you down that path?

Alexandre: Oh, man. Thank you for asking this question, I’ve gotta say this, because this means a lot to me. It’s a tough question to answer in a short amount of time because this goes into what I do and everything that I’m about to do. I’m very concerned about the state of movies. There’s still, of course, a lot of great movies being done. There will always be that. But in this, for lack of a better word, this age of content, I think we’re starting to lose track a little bit, perhaps, of the process of the great filmmakers. I’m talking the masters, the legends. Those who really have created those films that have become treasures for us.

I think it’s very important to take the time to understand what makes a movie like Alien or what makes a movie like Citizen Kane, or you can go down the list, Vertigo, The Exorcist, which is my next project, what makes them great? And how do these master filmmakers, how do they work on their craft and how do they think? What’s amazing to me is that when you start really digging deep into the process of those masters, you realize that they don’t think like other people. I feel like, to me, there’s a sense of urgency that this needs to be preserved. It needs to be preserved in a way that is not dry, that is not inaccessible, that is not just relegated completely to film studies.

The reality is that I think most people, the general population, people who love movies, are probably a little bit intimidated by this idea of film studies, this idea that there are film scholars, that there are intellectuals, that there’s all this stuff. And so, what I do is hopefully try to build a bridge between the general public and the idea of film studies. That bridge is what I want to convey. This infectious passion that I have for cracking movies open and making people realize that this is really something that we can all do and that in fact, that’s the great thing about movies, and in fact, the great thing about art is that the deeper you go and the more you understand what those people are doing, the more fun movies become, you know?

Brad: Yeah. We come to Sundance and it’s all about the new, what’s premiering here, what’s coming up. And I feel like the conversation is so about the now, we rarely look back. So when I see something like Memory, or 78/52, it’s a revelatory experience.

Alexandre: Thank you very much. I appreciate that. Thank you.

Lisa: Memory deconstructs the DNA of the Chestburster scene as an idea, tracing where the idea came from. The structure of your film starts with the zeitgeist, big picture idea, mythical level, and then goes down so specifically to the instant the film was shot, and then opens back up again in a really satisfying way. Where in the creative process do you start finding that structure?

Alexandre: This particular project has been very unique. I’m big on structure. I come from a dramatic writing background, so to me, structure and the script is everything. If it doesn’t work on paper, it’s sure as hell not gonna work on the screen. But what’s very interesting about the making of Memory is that I feel that a lot of the process of it came out of the unconscious, and I had to trust that. There’s a real intuition about where I had to go with this film. Well, it is about the Chestburster, but it’s a film about the resonance of myth and about our collective unconscious. I mean, let’s face it, it’s a film about Alien, but it’s a lot more than a film about Alien, right? I had to follow the intuition that this is not a scene that could be approached or structured in the same way as the shower scene in Psycho. It’s a different beast altogether. What intrigued me a lot initially was the connection between the Chestburster and Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.”

Brad: Blew my mind.

Alexandre: It’s cool stuff, right? It’s one thing that you can just say, “Oh, yeah, well, you know, this is just Ridley Scott putting one thing and just showing an image to Giger” and think no more about that. But that’s precisely what I’m trying to say, is it’s all these things. The images resonate with certain artists for certain reasons, and those reasons are not necessarily conscious. They do come from the unconscious. The fact that Dan O’Bannon and H.R. Giger met and the way that they met through Dune, and that they had the same preoccupations, that they were both working on their own Necronomicons, that they were both obsessed with H.P. Lovecraft and the fear of the unknown, all of those things put together … the parasitic wasps, the Crohn’s disease.

When we look at it, as you say, “Oh, yeah, it’s just a bunch of coincidences,” and well, okay, sure. Fair enough. That’s an argument to be made. My argument is that when a movie like Alien becomes as successful as it did in 1979, at a time when people were actually ready for the cute, cuddly, friendly alien, as Clarke Wolfe says very early in the film, I wanna look at this and say, “Why?” Why did this movie, against the grain and against the odds, become so successful? Because it was presenting us with ideas and images that we … and I believe this very strongly … that we, as a collective, needed to process and work through. Forty years later, we’re still processing and working through and finally having a conversation about, 40 years later, what makes Alien extraordinarily contemporary as a film.

Lisa: But the thesis that you’re making there, that society as a whole asks for art that answers questions, that parallels medicine or invention. Two different people invented the telephone at the same time.

Alexandre: That’s exactly right.

Lisa: Because the world needed a telephone.

Alexandre: That’s exactly right. And the same thing happens with movies. I’ll give you an example. It’s funny because I’ve never really heard people talk about this a whole lot. Regardless of where you stand politically, obviously we’re in strange times. When I watched the movie version, the new version of IT, I was struck by one thing and that is the fact that the reason why … and this is my argument … the reason why IT became a smash box office sensation at this particular time is because it is an allegory of Trump’s America. I’m not even gonna talk about the orange-haired clown, but if you leave that aside, if you put that aside, you’re talking about a group of kids, a diverse group of kids, who are essentially torn apart by this figure. The whole idea of the film is they need to find a way to stick together to defeat that.

Brad: Solidarity.

Alexandre: This idea that America is being torn apart and this message that, in fact, we’re not as divided as we think but we need to stick together, resonated in a major way with audiences. I don’t think people walked out saying, “Oh, yeah, that’s just what’s going on.” But that’s what it did. And I would certainly make the argument that if it had come out two years earlier, it probably would never have been the sensation that it was at the box office. So, the bottom line is, I think it’s important to pay attention to those things.

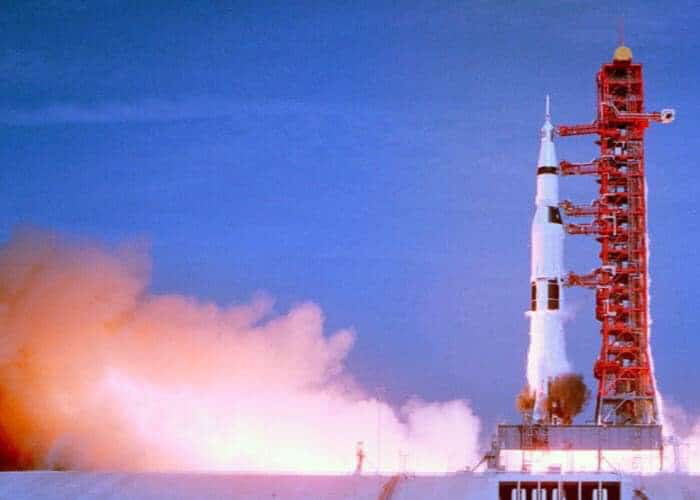

I will even go further and say in 1979, if Dan O’Bannon had not connected to that resonance of this particular myth, somebody else would have had to do that. Because we as a collective summoned that story. We needed that story to show up on the screen, and we needed to process those images and those ideas.

Brad: I was struck by how much love and attention you give to Dan O’Bannon. He tends to get dismissed from the story. Was he always going to be as strong a focus in your film?

Alexandre: Not initially. That’s the thing. Talking about the unconscious, I was introduced to Diane O’Bannon by Frank Pavich, who did Jodorowsky’s Dune, which is an amazing movie. Which, by the way, is another very poetic thing. Jodorowsky’s Dune director introduces me to Diane O’Bannon? It’s like, “Whoof, goosebumps.” But I was in LA with Kerry [Deignan Roy], my partner on Exhibit A, and a producer. That morning when we woke up we were going to drive to Diane’s house in San Diego, and I said, “I don’t know why I’m telling you this, but this encounter’s gonna change everything.” I had this kind of vision. We showed up at her house and she had all these boxes opened and all these papers.

Brad: She was ready.

Alexandre: I’m looking at this and I’m like, and there’s the screenplay, the original, from Memory. There are two versions of it. There’s Memory A and Memory B, which they’re very tiny little scripts because they’re unfinished. Storyboards from Ron Cobb and all these drawings from Dan. This one version of the script, alternate endings. There’s a one-note from Ron she’s saved on a little napkin that is actually in the film. You can’t read it, it’s unreadable. The way he writes is unreadable, but you get a sense that it’s kind of the first idea of like, “Oh, what if it comes out the chest?”

Brad: Oh, man.

Alexandre: Yeah. These little, just amazing things. I’m looking at all this and I’m like, “Oh, my God. This is it. This has to be about Dan. It has to be about really all of this stuff that was bubbling in his own process and his own unconscious since, quite frankly since he was a kid, but tracing back to 1971 when he wrote that screenplay They Bite, which is an unbelievable script, by the way.

Brad: I’d love to read it.

Alexandre: Well, I’m hoping that Diane will make it available at some point. The thing about They Bite, too, is if you love and revere The Thing, as I do, the Carpenter version of The Thing, I will just say that there are a few things in They Bite where you go, “There’s no way that Carpenter did not read that screenplay.”

Lisa: That’s cool.

Alexandre: Which is very interesting. So, I’ll just say that. I’ll just say that.

Brad: All right. Now I really wanna read it.

Alexandre: Yeah, it’s really great. It’s really great. At that point, it was clear to me that it needed to be an origin story. I was already, obviously, very interested in the mythology of it and the roots and the Francis Bacon and the Greek Furies and all of that. It only made sense to go all the way back, and then we got back to Dan O’Bannon, who is really the one who started it all.

Lisa: But this idea of, “Okay, we’re going to follow this idea back to its origins,” and you go to Egyptian myth and you dive in Giger’s work and all of that. There are just so many research rabbit holes that you can totally get lost down. How do you prioritize? There’s potentially no stopping point.

Brad: Yeah, there’s a lifetime of research.

Alexandre: For sure. For sure, yeah. To me, and this is where I have to put on my dramatic writer hat and go, “What is the story of this film?” It’s not, “What is the story that this fan would wanna see versus that fan?” Because there are always gonna be people who say, “I wanted more of this,” or, “I wanted more of that.” What is the story of this film? The story of this film is still about the Chestburster, in the sense that the Chestburster is the moment. It is the moment of Alien in the way that the shower scene is the moment of Psycho. It is the moment that everything led to it, and the moment had to work in order for Alien to resonate with audiences, and so many things could have gone wrong.

The reason that I have the opening sequence that I have, which I’m not gonna spoil, but the whole idea is that it is more than just a piece of material prop that is coming out of the chest or fake chest of John Hurt. The argument is that the emergence of the Chestburster in Alien is the reemergence of the Greek Furies showing up onscreen in 1979 to address unconscious patriarchal guilt that we need to work through as a society and to restore a balance that truly needs to be restored. And that’s what the Furies do. So if you wanna get really, really esoteric, then you wonder, “Well, are the Furies actually real? Do they really exist?” Well, it’s a force.

It’s like when I talked to Friedkin — The Exorcist project I’m working on — about the Devil. He doesn’t see the Devil. He’s talked to the Vatican. The Vatican exorcist doesn’t see the Devil as an actual physical being with horns and a tail, but it is a force, it is an energy that happens, that has to be reckoned with sometimes. I think everything we do in life and everything we do as a collective creates a ripple effect. So the Furies come back through time and they come back through mythology, through stories, through films, through things that we do in society when there’s something we do and there’s a certain guilt that comes out, and we need to process that. And so, I think that’s the whole argument that I make through Memory.

Brad: Before we leave, I don’t wanna stop this conversation without talking about that next project. You go from Psycho to Alien, and now you’re doing The Exorcist. How do you choose which subject to chase?

Alexandre: It’s very strange. Once again, I cannot even tell you, I feel like I am guided, in a way, because the Exorcist project was just as serendipitous. I was not planning on doing this. I was at the Sitges Film Festival with 78/52 and I was having lunch with Gary Sherman, the director of Dead & Buried and Deathline. Then there was a voice behind me that said, “Hey, Alex.” I turned around and it’s William Friedkin. And he says, “I’ve heard so much about your film. Just come over here. I wanna tell you some stories about Hitchcock.” And I’m freaking out. I’m like, “What’s going on?”

Then he watched my film and loved it. He sent me an email and said, “Next time you’re in LA, I wanna buy you lunch.” And then very quickly the conversation switched to The Exorcist. I felt there was something. He gave me essentially an opportunity to make a film. He said, “Look, just read my autobiography, and you find an angle, then let me know.” And so I went back to him and I said, “Look, if I want to make a film about The Exorcist, I wanna do something completely different from what’s been done before. I would want to use the Hitchcock/Truffaut model of interviews, where we sit down for a period of days and we crack open The Exorcist and we talk about your process as a filmmaker.”

This turned into a four-and-a-half day interview with Friedkin, and we’re still communicating a lot and I’m still gonna go back. We didn’t even talk about special effects, not once, but we talked about painting, we talked about classical music, about opera, about Citizen Kane, about his love for the Kyoto Zen Gardens; he was in tears talking about the Kyoto Zen Gardens. I mean, if you think what you’ve seen from us is good, and thank you so much for saying that you appreciate what we’ve done, wait until you see this project on The Exorcist.

Lisa: Stoked.

Alexandre: This one is going to be on a league of its own.

The post Alexandre O. Phillippe on the Preserving Great Conversations About Film [Sundance] appeared first on Film School Rejects.

, letting everyone know that he’s one of the good ones and defusing any awkward situation with a lighthearted remark. When Michael Burnham (Sonequa Martin-Green) voices a grievance over the handling of a mission, Pike sits with her and listens. He’s curious, eager to hear her point of view and even sees his mind changed on the issue at hand.

, letting everyone know that he’s one of the good ones and defusing any awkward situation with a lighthearted remark. When Michael Burnham (Sonequa Martin-Green) voices a grievance over the handling of a mission, Pike sits with her and listens. He’s curious, eager to hear her point of view and even sees his mind changed on the issue at hand.